Electric Topography: A Review Of Tokyo’s After Hours Music Festival

Formed by members of MONO, Envy, & downy with a focus on artistry over fame & marketing, the fest highlights the best of Japans post-rock scene & beyond

One night, just before dinner, I told my family, “I know I talk a lot, but there is a story that I really want to tell you, and if this story hadn’t happened, our family might not exist. Twelve years ago, when I lived in Portland, Maine, I spent most of my time writing, playing guitar and listening to music. Some friends told me about a band from Japan that was coming to town. They were called MONO, an instrumental post-rock band, and my friends said that I would really like them. They were right; the set was great. After it was over, I wanted to say something in Japanese to the band, but it had been five years since I had last studied or spoken any Japanese. What came out was, ‘Ongaku ha suki desu,’ or basically ,‘’I like Music.’ It wasn’t the most articulate or meaningful thing I could have said, but the band thanked me politely. When I got home, I took out an old Japanese textbook I had traveled with. I felt that all the years studying Japanese had been a waste unless I learned to actually speak it. Within six months, I was on a bus moving to San Francisco where I gained fluency through about a year-and-a-half of rigorous self-study. From there, I finally accomplished my dream of living in Japan. And, the band that sparked that move is one of the bands that I’m going to see tomorrow in Tokyo.”

The next morning, I woke up at 4:30 am and walked from my home through the sleepy scenery of Nagano to catch a 6am bus, trading the gentle mountains for the electric topography of Tokyo, the biggest city in the world. I arrived at Shinjuku station at about 10:40 am, and made it easily to Shibuya where, with the help of GPS, I weaved my way uphill through narrow streets packed high with eateries, adult toy shops, convenience stores, love hotels, and finally, a single city block containing four music venues: O-East, Duo Music Exchange, O-West, and O-nest. This is where the After Hours festival was to be held. In all, 31 bands were scheduled to play on five stages within an 8-hour time-frame.

The MONO show that I went to back in April of 2005 took place at SPACE Gallery, a non-profit art space and organization that believes in supporting experimental and provocative arts. They are funded by grants, one of which comes from The Andy Warhol Foundation For the Visual Arts. Fast forward a dozen years, and traces of both MONO and Andy Warhol had carried with me through time and settled to the forefront of my consciousness as The Velvet Underground’s self-titled album — the final track of which is titled “After Hours” — played in Shibuya’s O-East as the crowd gathered to hear MONO kick-off the festival.

Members from the bands MONO, Envy, and downy worked together to create After Hours as a way to provide a platform for musicians who focus on art and expression over celebrity and marketing. In a country where domestic artists rarely play small towns, and most tours consist of Tokyo, Osaka, and maybe Yokohama or Nagoya, it could prove to be a historic step in establishing a working-class touring scene that is independent from major promoters, television stations, and celebrity aspirations. In their own words on the festival’s website, the organizers have this to say about the overall attitude towards music in Japan:

“We feel that the country we live in, Japan, has the tendency to consume art and music as just entertainment… Japan tends to value the physical accomplishment itself more, as opposed to recognizing the power of influences that people and society bring to each other over a long period of time.”

While there is a certain level of this attitude existing toward art and music within other consumerist cultures, I do observe this to be an overwhelming tendency in Japan. For example, when discussing the quality of a band among my friends, colleagues, and family members, it is common to mention that they are famous, whereas the content or vision of the project is often the secondary discussion. The idea that fame is not always equal to quality or artistic integrity is largely lost on the masses who consume J-pop where, no-matter what the genre, everything is more-or-less a love song, or rock-n-roll cliché.

Again, in the words of the promoters of After Hours, “What is important with artistic expression is not the outer layer, but what remains deep in the conscious.” I see this as a two-edged sword where the second layer of corporate rock simply exists to separate people from their money, and possibly, to keep them complacent in their daily routines. On the flip-side, we have independent artists, where the outer layer is music and some merchandising, but the lower layer consists of people fighting to live by their values and their art through a community of like-minded individuals who also see beyond the veil of corporate seduction.

Back to the O-east; it is the largest of the four venues with a capacity of 1,300. The space featured a balcony; access to a bar where smoking was permitted; a quick access lane to the restroom, that really helped when the place was packed; and two stages within about twenty feet of each other. One was considerably larger than the other, with the second stage off to stage right and at a slight angle from the main stage. The club was dimly lit, with some red sections illuminated on the wall, and a dull black and purple checkerboard pattern on the floor. There were plenty of padded rails coming out of the floor, in part to provide a spot to lean on, in part to prevent moshing, which, along with stage diving, was warned against on some postings throughout the hall.

I had met up with my friend, Sam, who records and plays in a band of his own. “Man, look at all those rails.,” he commented. “That would never fly in Melbourne.”

Sam introduced me to a friend of his who plays in a two-piece band, who in turn introduced us to three people who are part of a three-piece band. I asked them about performing in Tokyo. I know that, in places like Nagano, the obstacles to doing gigs are a limited number of venues, limited fans, and the cost of everything falls on the shoulder of the performers. “The problem with Tokyo,” one of the musicians said, “is that there are too many venues, so it is easy to play shows, but hard to get a following.”

It was past 12:30, and people were already drinking cans of beer and cocktails. The crowd was diverse with a lot of English speakers. Outside of an English teacher training, or Costco in Gunma prefecture, it was the highest concentration of non-Japanese speakers I have ever been a part of in Japan. This speaks to the popularity and appreciation that the international community has for non-corporate music, something that really hasn’t caught on in present day Japan.

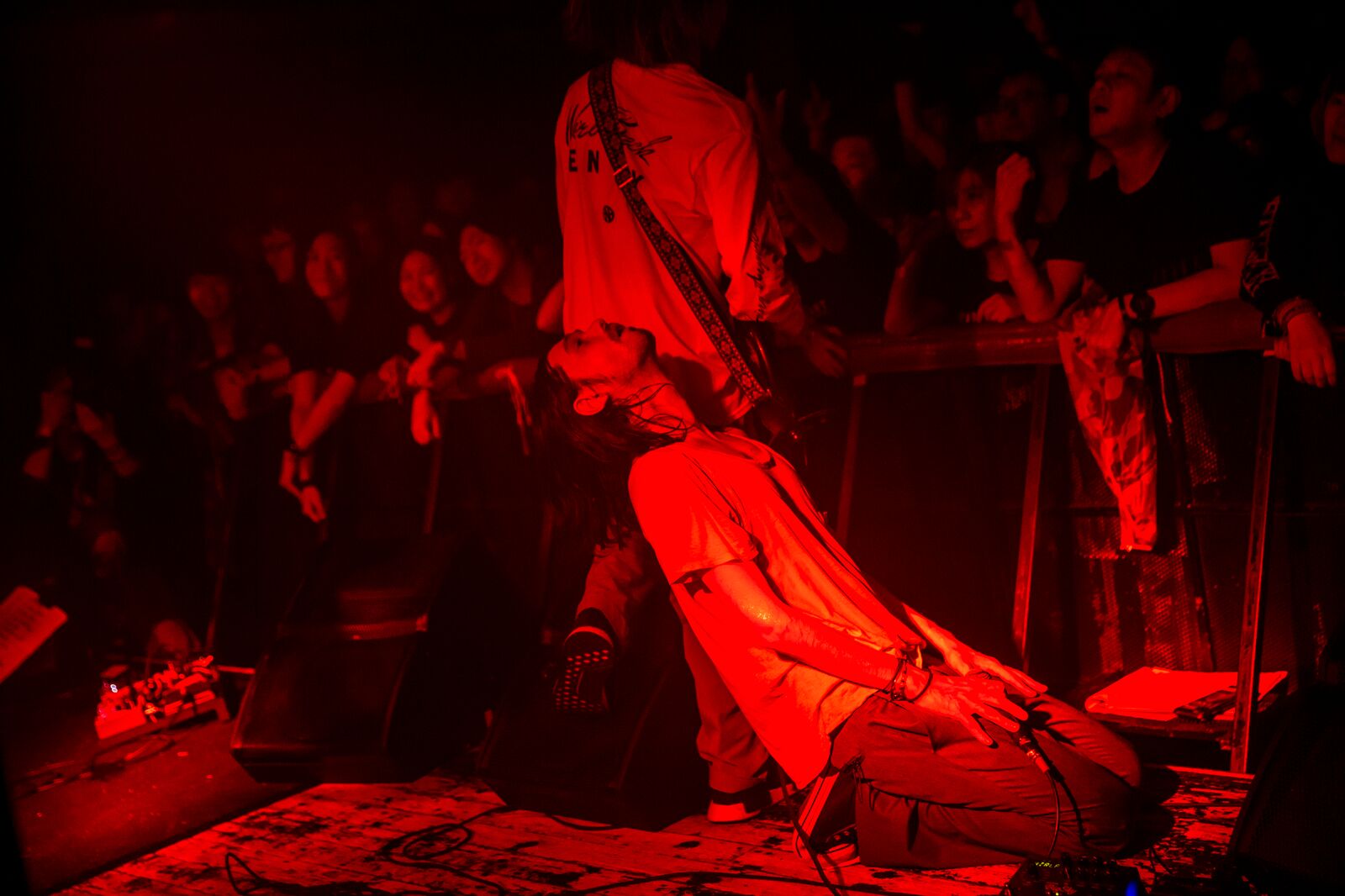

photo by Yoko Hiramatsu

By 1pm, The Velvet Underground album had neared the end of its second cycle when it was cut off. Three members of MONO walked out to their instruments to applause, followed by a pause. Then Tamaki, the bass player, came out to a massive applause. She stood at a microphone stand stage left and addressed the crowd briefly, in Japanese.

“Welcome to After Hours, please enjoy the festival all the way to the end.”

There was a third applause, and the band started in on their 50-minute set featuring a handful of tunes from different eras in their catalog. MONO‘s songs tend to run for over ten minutes each. Their stage setup consisted of their guitar player, Yoda, standing stage left; a seated guitarist, Taka, stage right; the drummer, Takada, in the back; and Tamaki standing front and center, spending time between xylophone and bass. Takada started the set with mallets, as he did 12 years ago in Maine, before moving on to sticks and brushes. The two guitar players communicated changes with occasional glances, nods, and fist pumps. The music of MONO starts quietly, builds to a peak, and follows several contours before often ending in a crescendo. Rather than dazzling with lightning fast fingers or abrupt changes, the focus of the group’s sound is on arrangement, complexity of the compositions, and the emotions expressed through the passage of time within each song. At one point during middle of their set, while wearing a blouse as loose as his long hair, Taka rose from his seat for effect, and, holding his guitar to the amp, created a deafening feedback that lasted for over a minute. The audience showed approval, responding with intensified nodding and introverted art-rock movements, as the sound continued. The guitarist subtly pumped his fist twice and the unavoidable noise that had enveloped the whole room stopped dead. The crowd erupted. MONO finished their set with a newer song, the title track from their 9th and latest studio album, Requiem for Hell.

While many people were surprised that MONO was performing so early, it was really the perfect way to set the tone for what would prove a remarkably dynamic day of introspective music.

I stayed put in O-East to catch the first second stage act. As the house lights went on, The Velvet Underground record picked up again. That single album would be the between-set music for the entire festival at every venue.

photo by Eisuke Asaoka

The second band was Klan Aileen, a two-piece comprised of drums and guitar. According to the After Hours website, the duo has been performing off-and-on since forming in 2012, and have released some material in limited-edition cassette-only format. Their sound is pretty unique with a 90s alternative rock influence. In fact, the overall feel of After Hours harnessed the best of the independent spirit of 90s rock, both in the anti-corporate feel, and in the experimental sounds and genre blending that the bands executed.

Klan Aileen’s music featured a lot of sampling, along with some soloing in their largely fast-paced chord-driven compositions. The singer, Ryo Matsuyama, is tall with shaggy hair that falls just below his ears and over his eyes; he sings in a withdrawn way with some echo effects on his vocals. Though I had only heard their song, “Happy Memories,” previously, I recognized it from the drummer, Takahiro Takeyama‘s count off, which I was impressed with, seeing it as a sign of a tight band. Despite being on the smaller stage, the venue set was pretty well attended.

Next on the bill was downy, on the main stage of O-East.

photo by Eisuke Asaoka

Of the three bands organizing the festival, downy is the one that I was least familiar with. What I knew about them was that they were made up of several talented musicians who are all involved in other side-projects, and that some of them are even video artists who create the projections that are part of their live show. The avant garde artist in me was drooling over the chance to see them, choosing to learn about them live, first, rather than familiarizing myself with their body of work, beforehand.

Their front man, event organizer, Robin Aoki, addressed the room in a deep voice, welcoming the crowd, mentioning how special of a day it was, and encouraging people to drink and be merry while enjoying the music. As he spoke, there was static fuzz projected over the band that spanned the entire stage. As the music started, abstract animations played and changed along with it. I was surprised by the range of Aoki’s voice. When I think of post rock, I imagine instrumental bands, or screaming vocals, but here was a man with a low voice, singing at a high octave over complex instrumentation. The bass player switched between an electric and standup bass, and Aoki switched between synth and guitar.

Thinking of his words encouraging people to see lots of bands, I decided to head out and explore the other venues. My next stop was just downstairs. O-East is on the second floor and, on the first floor is Duo Music Exchange. I assume that it is called “Duo” because there are a pair of giant, round concrete brutalist columns in the middle of the hall that obstruct the view of the stage. However, the sound quality is still top notch.

photo by Yoko Hiramatsu

When I got downstairs, World’s End Girlfriend was finishing up, so I only caught the last bit of their set. There had been a lot of buzz about this group, which is actually the project of a single composer, Katsuhiko Maeda, who performs with a backing band. I had decided to see downy instead, and the choice to catch parts of both of their sets shaped the rest of my festival experience. Being a fan of lyrics and vocalists, I had wanted to limit the number of instrumental acts that I attended, but this was well worth it. There was a massive projection of falling white dots cast in front of a soft pastel purple background. Maeda had really long black hair and was manning both a laptop and a guitar. There was a violinist seated stage left, who performing from sheet music, as well as a drummer, a bassist, and a cellist, who I couldn’t see because of the column, but who was reportedly, also playing off of sheet music.

Whereas downy had their projections restricted to a rectangular backdrop, World’s End Girlfriend‘s projections wrapped around the walls, and looked more like confetti than any animation. The effect was great and, from what I witnessed, the band really was as good as the hype, with more classical musicianship and, near the end, almost a punk or grindcore feel to it. With their combination of various influences, their sound was the very definition of experimental.

photo by Eisuke Asaoka

I stayed in the Duo Exchange to see the next act, Tha Blue Herb. I had been curious about them both because of their cheesy band name, and because I wanted to see if they actually came off as major stoners, which would be quite a rebellious act in a country that will lock a person up for several years for possession of less than a gram of marijuana.

While a lot of the talk of the festival centers around post rock, heavy sounds, and instrumental bands, I noticed that there were plenty of hip hop artists scheduled. Tha Blue Herb looked to be the most standard hip-hop act in the lineup, consisting of just a DJ and an M.C. The video that they posted on The After Hours page was about the devastation of the 3/11 earthquakes, something that I wasn’t really sure how to take. Were they simply an opportunistic act, like Macklemore, who just chooses a popular topic to “rap” about it? It turns out that they were much more of a barebones hip hop outfit, with the MC basically rapping non-stop, even as he addressed the crowd. It was really hard for me to understand some of the lyrics, but what I had originally thought of as a minor mid-card act was actually at full capacity.

A friend of mine was going to join me for their set, but the venue was full, so I left after getting a feel for them. In all honesty, it is incredibly hard to understand rapping in a second language, and although I really appreciated that there was a group that focused so much on lyrics, I was just as happy to go check out another venue and some more bands at O-West.

photo by Kana Tarumi

Over in O-West was Wang Wen, a 6-piece from Dalian, China performing well-orchestrated music with an effective focus on technique. Formed in 1999, they count other post-rock pioneers like Mogwai, Mono, Explosion in the Sky, Tortoise, and Godspeed You! Black Emperor among their influences. The trumpet player stood out by utilizing his instrument in a non-traditional and, at times, almost percussive way, while the front man played his guitar with a violin bow. There was a sample of an old radio broadcast playing over one song; it sounded Japanese, but I couldn’t make out any of the words. After the show, they addressed the crowd in English, stating how glad they were to come to Japan, and hoped that they could return.

I overheard someone comment in English, “So, I just realized that the common language between Japan and Hong Kong is English.”

photo by Yosuke Torii

I had wanted to go see the hardcore band Killie next, but the line looked incredibly long to get into see mouse on the keys, so I stayed. mouse on the keys features two pianos, a drummer, and a saxophone – it’s high spirited music with very busy fingers. After the first song, I wasn’t really in the mood for live piano music, or another instrumental set, although I do want to explore their recordings. I decided to go out to see if Killie was still playing up in the O-nest, the fourth and smallest venue, which only holds 250 people.

photo by Kana Tarumi

I was fourth in line, but I got in for the last bit of the set. It was packed up to the door like a small box. In addition to being the smallest venue, the stage was also the lowest and hardest to see from the back of the room. I could only see the heads of the members of Killie. The lighting was bright, but with no movement, adding to the rawness of their angry sound. I only caught the very last of their performance, but would like to get the chance to see them again. The band was over, and mouse on the keys was too crowded to get back into. Surprisingly, there was no line to get into the O-East where Tricot was playing.

photo by Eisuke Asaoka

Tricot consists of three main members, all women, with a touring drummer. Hailing from Kyoto, they perform complicated math-rock type rhythms over pop tunes. Between songs, the singer, Ikumi “Ikkyu” Nakajima, mentioned how cool it was that her band could play with all the others at After Hours, and how it showed her how cool her band was. Really not sure why it wasn’t more full.

I was getting hungry, so I decided to take a walk in search of food and ended up at a bar called B.Y.G. that features a vinyl DJ playing classic rock and blues. There was a five-dollar happy hour menu, so I ordered a beer and a pizza while relaxing under the low ceilings. The walls of the bar were littered with signatures, some from famous bands — I remember seeing a message from The Strokes. I thought about seeing DJ Krush, but with so many Envy shirts in the crowd, I decided to get into the Duo Music Exchange before it filled up, and wait for their set.

photo by Eisuke Asaoka

It’s been a year since vocalist, Tetsuya left Envy, and an official replacement has yet to be announced. To account for this there were multiple vocalists helping them out, starting off with Kent Aoki from Heaven in Her Arms, and the sound was good. Aoki even wore a black baseball cap, so the band looked very similar. Their sound has been compared to MONO, except with vocals and a bit more of an edge. I left the Envy show a little bit early to see if I could get in to LITE, but it was full, so I went back to the O-East where Unhellys were performing on the 2nd stage.

photo by Kana Tarumi

Uhnellys is made up of two members: a drummer/backing vocalist name Midi, and a front man, Kim, who played guitar, trumpet, sang, rapped, and controlled some sampling. MIdi also had some sampling capabilities. People were really dancing to them in a more unchained way than I had witnessed at other acts. They were probably the funkiest of the bands that included rap elements that I had seen there. Also notable was the guitar work and how the trumpet added a jazz element. As far as two-member bands go, these two had an incredibly full and complicated sound. Plus, they played to the crowd with an energy reminiscent of the most original sounding and defiant punk bands.

photo by Miki Mastushima

For some reason, the last acts of the night were not as crowded as the ones earlier in the day. I started off catching the beginning of Boris and the audience was not nearly as packed as I had anticipated. I asked Sam if he knew why they were called Boris, and he said something about a Melvins song*. The Melvins influence is real, but the musicality of the group kept me way more engaged than any Melvins set I had ever seen. They were the loudest of the bands that I saw at the festival, and each of the three members played to the room incredibly well, with the drummer, Atsuo, slowing down some of the stick work to enable him to signal the crowd before hammering beats. The smoke machine, laser lighting, and the giant gong, along with the Satan horns, all added an aesthetic that was, perhaps, a little more light-hearted than some of the other more traditionally artistic acts, yet the music showed how serious of a band they were, earning every bit of recognition that they get. I didn’t stay for the whole set; I got too excited about all of the possible bands that I could see, so I headed to eastern youth, hoping to catch a more traditional rock band.

[*Editors note: Boris takes their name from the opening track to the 1991 Melvins album, Bullhead]

photo by Kana Tarumi

I walked into the O-East by mistake, and was pleased with the warm sights and full sound of the veteran post-rock outfit, toe. They’re yet another band that I would love to see play a full set, but I continued down to eastern youth, after catching the end of only one song.

photo by Eisuke Asaoka

Though not exactly a “youth” anymore, the singer, Hisashi Yoshino, is still youthful and plays with plenty of energy. He made a comment about young people, while mentioning his own age, and got some laughs, before going back into more material. Nearly 30-years into their career, eastern youth continues to endure, after abandoning their image as a highly successful oi! punk/skinhead trio early on (1989 – 93), and redefining their sound with more indie rock and post-hardcore elements over the years. I would have stayed for the whole set, but instead went up to the O-Nest where I ended my After Hours experience with Crypt City.

Crypt City isn’t a band that I even really considered seeing when I was planning my festival order, but I’m glad that I did. A rarity compared to the other bands at the festival (other than Envy), their front man, Dean Kessler, was strictly a vocalist. Rounded out by founder/bassist, Kentaro Nakao (Number Girl, Art-School); drummer, Masahiro Komatsu (Bloodthirsty Butchers); and guitarist, Masafumi Todaka (Art-School, Monoeyes); the music was hard and fast — more punk than metal. Before the first song, Kessler, who is originally from New York, addressed the audience in skillful Japanese to the crowd’s pleasure. Once they started going, the O-nest was hopping, and there was even a some cautious slam dancing going on for one of the numbers.

photo by Yosuke Torii

After the show, I ate dinner on a sidewalk patio, watching all different types of people walk by. The mass of humanity in Tokyo is truly impressive. During the festival, I felt as if art and expression were the center of the world, so it was a bit of a shock to be so suddenly reminded that commerce is still the overwhelming force.

After my burger, I hopped on Tokyo’s famous circular Yamanote subway line, and headed to Tokyo Station where I was to catch the overnight budget bus back to Nagano. The plan was to sleep on the bus, go home, take a shower, and go to work and type up my thoughts about the festival. The highway buses often include an umbrella-like cloth head-cover that you can pull over to give yourself a little dome of privacy — it helps with the sleep. I woke up around 6:30 in the morning by Nagano Station’s far-from-famous East exit. From there, I walked a half-hour through the cold, and fresh mountain air, arriving home at 7am, just in time to wake my kids up, and help get them ready for school.

Nobody asked how the festival was; they all had their own concerns, which were more important at that time, and I was happy to be back with them. After they all left for school, I put on my suit and went to prepare English lessons for the upcoming school year, and type this article after that was done. That night, still in my suit, I went to a formal school drinking party, and found myself seated in a glittering hotel banquet room at one of several round tables that were equipped with lazy Susans. The high-ups gave their speeches, the new teachers were honored, and people took turns pouring drinks for each other. It was a good time, but a very structured time; it was certainly not art, though there was cultural aesthetic oozing throughout the room.

Once all of the communal beer bottles had been emptied, I quietly made my way out of the hotel, and walked through the dark West Nagano streets where the city seems almost rural. Past the darkened shrine, the street was glowing red and green from crossing lights telling people who weren’t there when they could and could not cross, due to danger from cars that were not there. Taking notice of this societal control message, I loosened my necktie noose slightly allowing myself to breath. Thoughts rose of the passion with which the festival organizers spoke of their project; the pride and enthusiasm in the voice of Robin Aoki, as he spoke of After Hours; the stimulation of being around so many artists of integrity; and concert goers whom, all of which, at one time, saw through the illusions of society and etiquette to seek out art and artists who more accurately reflect their own worldviews. Taka, not happy with the label subculture after years of tirelessly travelling the world and seeing the power that art has. Envy, continuing through several decades, playing music that they love without considering selling out to become TV personalities.

As the tie loosened, I felt a small ache in my neck from a day of standing, and dancing, and rocking my head to the music. I got home where my family was asleep, and a hot bath was waiting for me. Just what I needed to further contemplate the thoughts that came from attending After Hours, a festival that will stay with me and find its way into my own art and writing for many years to come.

WOW Nice Article !

And for all those japanese old school postrock lovers here you have these guys: BLAK

Like with Mono, I’m in love with them so I decide to promote this band as much as I can !

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=etr1uL_39mE&t=3s

https://www.facebook.com/thisisblak/