An Evening With John Carpenter @ Paramount Theatre [Seattle]

Following his 2nd album of non-film compositions the master of horror presents a live career retrospective through new musical works and classic soundtracks

An Evening With John Carpenter

Paramount Theatre

Seattle, Wa

6/14/2016

We were ushered into Seattle‘s majestic Paramount Theatre and through a set of double-doors to the main floor, just as the scheduled 8pm set time was hitting. As the security outside emphasized, this was “an evening with” John Carpenter, meaning that there wouldn’t be any opening acts and, if we didn’t want to miss any of the show, it wasn’t recommended to roll in fashionably late. After locating our seats, I grabbed my camera bag and, moving up toward the stage, noticed that there were only 2 other photographers. Looking around the room, I was a bit disappointed at the low turnout, as well; especially for an event that I expected to sell out immediately — I put in my press request back in February, when it was first announced, for that very reason. It was still early and people could be expected to roll in late, not realizing that a performer would actually be taking the stage “on time” for once, but it was already fairly evident to me that this event would be shamefully under attended — the fact that there wasn’t anyone lingering outside of the venue for me to give a free extra ticket, before heading in, did little to contradict this assumption. Thankfully, the night proved rather quickly that anyone who didn’t bother to show up had really dropped the ball on this one.

There were a few factors that, undoubtedly, played a role in the tour stop failing to pack the 2,807 capacity theater on a weeknight, but, ironically enough, Carpenter‘s name recognition may have actually made one of the biggest impacts. Sometimes, being well known isn’t enough; it’s about what you’re well known for. When I’ve talked to people about going to see him live, whether it was before or after the show took place, the majority of them weren’t even aware of the tour, but everyone recognized the name, and almost all of them were puzzled about what a live appearance could possibly entail. Was it a lecture? Was he showing some films? Was I even referring to the same John Carpenter whose name they’d seen attached to so many genre defining cult films, over the years, from They Live and The Thing to Big Trouble In Little China? What was he doing here; promoting something? The fact that the Paramount is known for hosting much more than just concerts, including touring Broadway productions and speaking engagements by figures like Anthony Bourdain, could only work to increase confusion.

It’s interesting how identifiable John Carpenter is as the creator of the Halloween franchise and, in turn, how automatically we are all conditioned to associate the film with its brilliantly eerie theme song, yet that line between the iconic score and the fact that Carpenter was the one who actually composed it is far too rarely drawn. In fact, he’s composed the music for the majority of his films. Perhaps another irony is that, because his soundtrack work is so phenomenal — melding effortlessly into the visuals, helping to set the tone, and supporting the storyline in a way not many can achieve — his film music is often so effective that it becomes virtually inseparable from the larger project and, in becoming so, can lose its identity beyond just another component in a John Carpenter production. Many of those who do know of his composition work are still completely unaware that he ever released Lost Themes, an entire album of brand new non-film related tracks through the Sacred Bones label, last year, let alone a follow up just in April. And then, there’s the rest of us who are up on all of this, but still had no clear idea of what to expect from a live John Carpenter concert tour. When the information came through that it was being officially listed as a “career retrospective,” it immediately shot to the top of my list of must see performances this year.

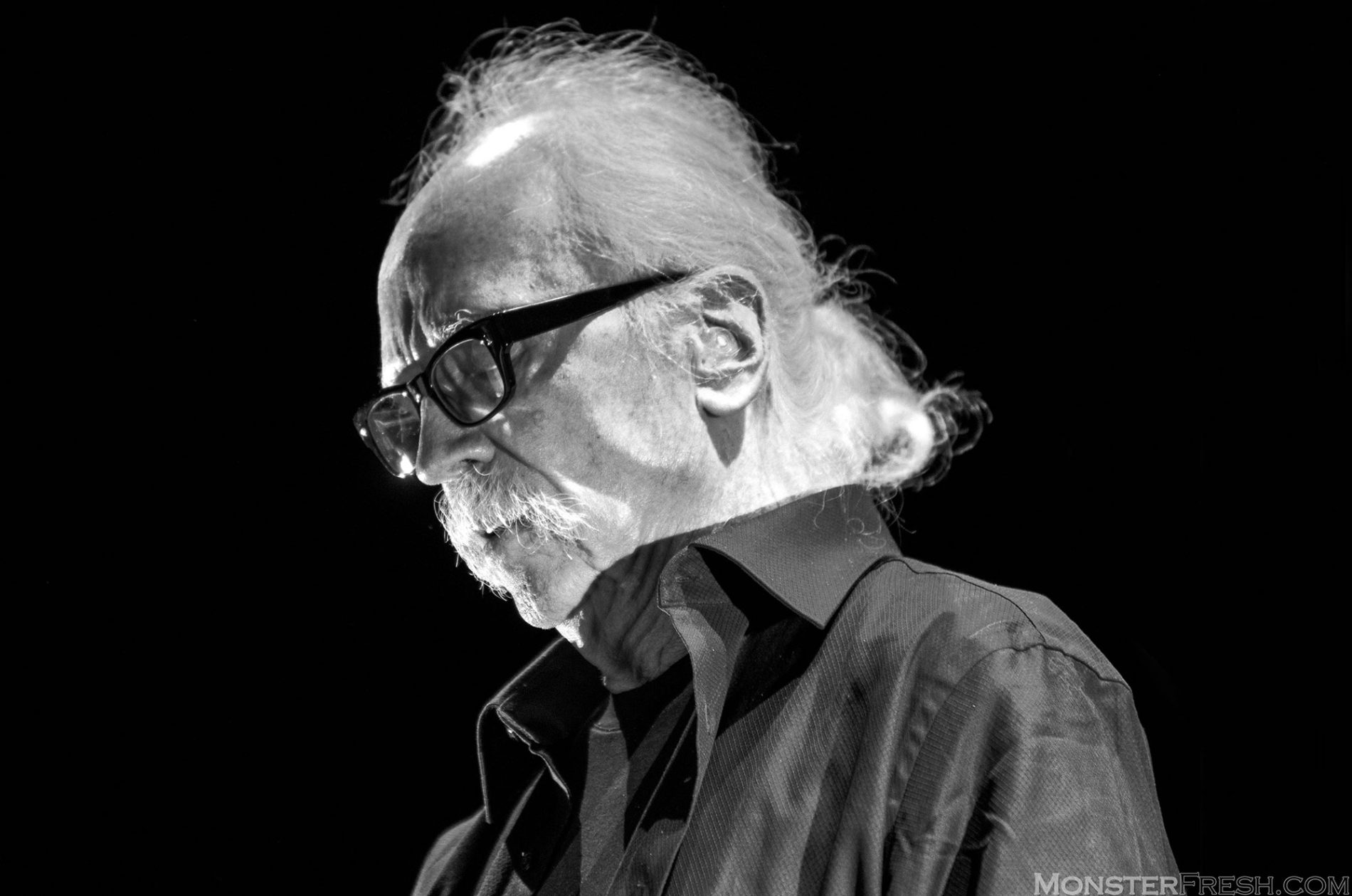

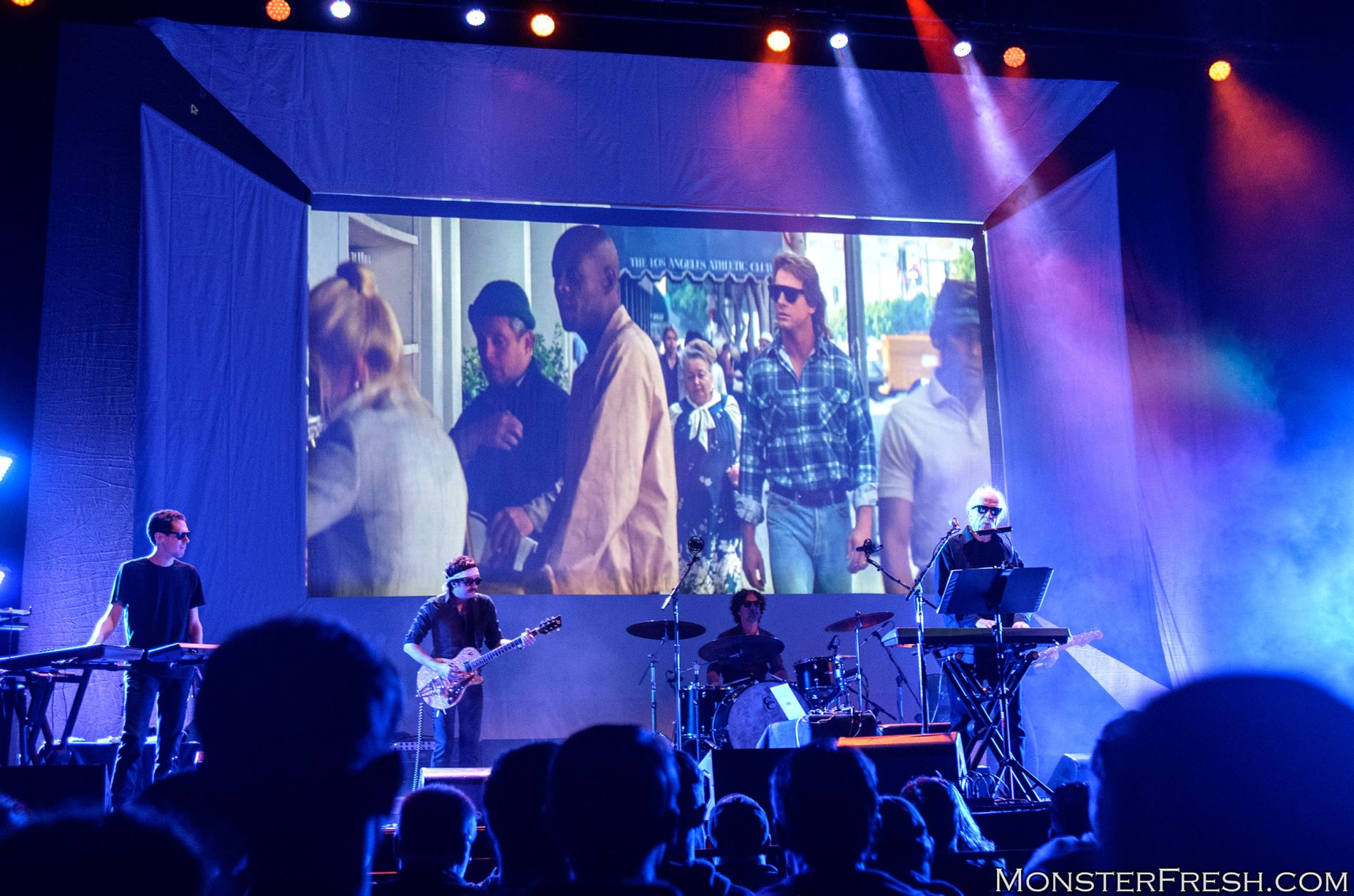

The man of the hour entered from the wings and planted himself behind a synthesizer and music stand stationed center stage. He was flanked to his right by Cody Carpenter, his son from his first marriage with scream queen/author, Adrienne Barbeau (The Fog, The Thing, Swamp Thing, Creepshow, etc), behind a second synth set up. Manning a guitar to his left was his godson, Daniel Davies — now 34, the son of Kinks guitarist/songwriter/vocalist, Dave Davies, moved in with the Carpenter family as a teenager. Set further back were John Konesky, John Spiker, and Scott Seiver — all from Tenacious D‘s band — on guitar, bass, and drums, respectively. Behind them all was a large projection screen.

The first song that they kicked into was the title theme from Escape From New York, the 1981 futuristic sci-fic action flick featuring Barbeau and known for helping, former Disney child star, Kurt Russell finally break out of the squeaky clean image that had plagued him, through taking on the role as stubble-faced eye-patch sporting mercenary protagonist, Snake Plisskin. Segments of the film projected behind the band, as they performed. Images of the dystopian wasteland, wherein the entirety of 1997 New York City was to have been transformed into an over-sized prison housing the worlds most dangerous criminals, flashed, as the steady, yet propulsive, beat pulsed forward. As with the rest of his work, the track laid the ideal setting for the visual landscape — a landscape which, in this case, was actually filmed in downtown St Louis; the aesthetic benefiting from a huge fire that had gutted the area in 1970. Shot through the lens of 1940s film noir and resulting in a high watermark in the director’s career, Carpenter had originally written the film in the mid-70s during the Watergate scandal, when the United States had an all time distrust for political leaders, but it was rejected by studios, most likely, for a similar reason. The filmmaker kept the film in his back pocket until he had slightly more pull and released it in the aftermath of the Iranian hostage crisis, when the public was much more receptive in the pre-Rambo era. The Escape from New York theme is among 4 of the director’s classic tracks that he recently re-recorded with his new band for a pair of special edition 12-inch vinyl releases; this one appearing as the B-side with the Halloween theme on the reverse.

Next came the main title from 1976‘s Assault On Precinct 13, a song that was re-recorded for the other 12-inch release (backed with The Fog theme). The low budget exploitation suffered a major controversy surrounding its release, due to a scene where a young pigtailed girl with an ice cream cone (played by Kim Richards) was shot point blank by members of a street gang. To everyone’s delight, they made sure to project that clip during the show. In many ways, the music from Assault On Precinct 13 laid the groundwork for what would become Carpenter‘s trademark sound, with its brooding synths trudging over ethereal sustained keys in the backdrop. Believe it or not, the soundtrack was created over the course of only 3 days with the assistance of USC electronic music teacher, Dan Wyman. Working with synthesizers and doing the work himself, because they couldn’t afford a soundstage and he figured that he could get “a big sound for cheap,” Carpenter‘s plan was simply to come up with 3 to 5 basic pieces that he could insert into various sections of the film — he hadn’t begun writing to footage yet, at that stage in his career. It’s amazing then, to think how influential that sound went on to become, both in his own work and on that of those that came after him.

The next couple of tracks, “Vortex” and “Mystery,” both come from Lost Themes. The way that the album came about was somewhat interesting, as the music wasn’t created with any real intention behind it other than for John to jam out with his son — and later, his godson — during breaks from the two of them playing video games. The story is that Carpenter had recently gotten a new music lawyer who asked him if he had anything new in the way of material. Since all that he had was the music that he and Cody had been messing around with, which was, more or less, just improvised, he handed that to him. Not long afterward, he received a call informing him that he now had a record deal. Apparently, John Carpenter is a huge fan of video games, which is one reason why someone like Metal Gear Solid creator, Hideo Kojima, hasn’t been sued over blatantly pilfering aspects from Escape From New York. Then, of course, there’s the Mortal Combat character, Raden, which was modeled off of Lo Pan‘s lightning demi-god from Big Trouble In Little China. In 2002, The Thing even received it’s own video game treatment in the form of a first person shooter. Things definitely come full circle and I love the idea that, in his later years, someone who has worked as tirelessly to permanently affect our culture is just relaxing with some video games and jamming with his kid. What I love even more is that he was able to create a whole new chapter in his career taking him on the road to tour his music live, simply based on something that he was doing to break the monotony of all that button pushing.

Carpenter announced, “Most of my career, I’ve composed the music to scary movies, slasher flicks, and ghost stories.,” before going into the main theme from The Fog, as fog poured onto the stage. Following this, the entire band put on their black sunglasses signaling “Coming To LA” from the 1988 sci-fi thriller, They Live. The song begins with a short chunky riff punctuated with a floor tom, before pausing and resetting itself. Each time it would end on that drum hit, one of the classic subliminal messages from the movie would be projected onto the screen in the trademark black on white font. OBEY. MONEY IS YOUR GOD. SUBMIT. CONSUME. After the fourth time, the song eased into itself more fully and an image of the film’s late star, Roddy Piper appeared on screen to a roar of applause. These little videos were wisely edited to please the real fans with additional cheers accompanying the “I’m all outta bubblegum” clip, where he shoots up the bank, and the iconic alley fight scene that is intentionally drawn out to a hilariously absurd degree. They Live was written as a response to the Reagan era and the blatant obsession with greed in the 1980s. When discussing the filmmaker’s cultural impact, it’s a project that can not be overlooked. In fact, street artist, Shepard Fairey, virtually, built a career off of referencing its themes, directly; specifically, with his OBEY campaigns that utilize the exact same font and presentation as the movie.

When they played “Main Theme – Desolation,” from The Thing, it was announced that it was in honor of its composer, the inimitable Ennio Morricone. Carpenter didn’t do the soundtrack for the film, partially because, after operating with a different level of freedom for so long, he was now working within the structure of a major studio for the first time. He didn’t write the script for this one either. Easily the most difficult film that he’s ever been involved with, there was everything from safety concerns with the freezing weather to the obstacle of filming such a large ensemble together scene after scene. Not the least of the issues was the idea that they were remaking a classic, or that the film came out the same day as Blade Runner and was so much more depressing than Universal‘s other alien film that they were releasing, E.T. Upon it’s release it was rejected by both critics and fans so severely that, according to John, at least one article was even published with a headline suggesting that it might be the most hated film of all time. These days, however, it’s considered one of the greatest horror films ever made and the one that Carpenter believes may be the greatest film that he’s ever done. At the time, this was a turning point in his career, with Universal coming to him on the heels of his success with Escape From New York. If The Thing would have become a huge hit, it would have changed the entire trajectory of his career.

After playing “Distant Dream” from Lost Themes II, the horror master said, “I have a friend. We’ve made 5 films together,and the most fun we had was when we went looking for a girl with green eyes.” That’s when the band played “Pork Chop Express” while projecting footage from what is arguably his funnest movie, Big Trouble In Little China. [The actual theme song has a horrifically 80s music video worth checking out, if you haven’t seen it yet.] Ever since directing him in the 1979 Elvis made-for-TV movie, Carpenter has loved collaborating with Kurt Russell, appreciating the strong work ethic that he acquired growing up working on all those Disney films. The studios, of course, didn’t always see the appeal. One of my favorite stories is about the role of Big Trouble protagonist, Jack Burton, initially, being offered to both Jack Nicholson and Clint Eastwood, each of which turned it down. As Carpenter tells it, the studio believed that they were going to be getting the next Indiana Jones with the film, only to wind up with a main character who believed that he was the hero, when he was really the sidekick. The fact that Russell chose to play him as an oblivious, blowhard John Wayne knockoff only made it that much better.

Following were two more songs from the first Lost Themes album, “Wraith” and “Night,” the latter of which he introduced by claiming that, “Up until this point, most of the songs have been uncharacteristically positive” and that it was time to “go a little darker.” None of the non-movie tracks were treated to any projections, but with this one having such a great music video to accompany it, it might have been a good opportunity to make an exception.

After making a pretty straightforward comment about how, in his career, he “directs horror movies,” Carpenter enthusiastically added, “Scary movies will live forever!” At this point, that unmistakable Halloween theme began. This was the first film where John Carpenter took a note from director’s of his youth like Alfred Hitchcock and had it written into his contract that his name would be placed above the title in all advertising and promotional materials for the project. This practice, which he continued throughout his career, worked brilliantly to create an instant name for him as an upstart in the industry, implicating a bigger presence for the director, before he’d actually achieved it. By plastering posters with “John Carpenter’s Halloween” or “John Carpenter’s The Thing” it put the filmmaker in the forefront, acknowledging that these films were the vision of one man and, coupled with his unique, finely tuned aesthetic, it created a brand for movie goers to easily attach themselves to. What I love so much about Halloween in particular is how, at least in the first one, it feels like something that could actually happen. There’s no supernatural figure haunting anyone, just a guy who’s kind of fucked in he head walking through a neighborhood breaking into homes. The concept behind using such a blank mask and employing shadows and dim lighting is that it allows the viewer to project their own thoughts into the film to the point where many even believe that they’ve seen things aren’t actually ever there. The music itself provides a similar tension and canvas for our paranoia. What I loved so much about seeing the theme performed live is that Cody was the one playing that eerie-as-fuck melody on the keys, with his dad looking over to him as his horror classic rolled in the background. As someone who has a son of my own, it’s hard to believe that they aren’t living some sort of dream together with this tour.

After playing “In The Mouth Of Madness” and leaving the stage for a quick break, the band returned for an encore with Carpenter asking, “You want some more?” Following “Prince of Darkness: Darkness Begins,” and a cut from each of the Lost Themes releases, the frontman asked us to all please drive carefully home, warning that “Christine is out there.” The show ended off with “Christine Attacks (Plymouth Fury).” Another film that he didn’t write himself, Christine came about after John was originally supposed to direct a completely different Stephen King film: Firestarter. Following the lackluster response from The Thing, Universal tried to cut his budget down to $5 million, so he walked away from it and took on the murderous car project instead, primarily, because he needed a job. These days, he views the motion picture much more favorably, or, at least, well enough to close out a performance with it.

John Carpenter‘s life could have gone in any number of directions and been redirected at any number of moments — in fact, it has. Assault On Precinct 13 wasn’t John‘s first feature film; Dark Star had already been released by that point. Although that film led to co-writer, Dan O’Bannon going on to write Alien and even finding computer effects work on Star Wars, it was, essentially, still just the thesis they’d created at USC film school. Since no directing job offers were coming out of it, Carpenter got to work making a living as a screenwriter, until the opportunity to make Assault — albeit, on a shoestring budget — changed all that. Like Escape From New York, the film diverts from the “horror” label that became so synonymous with the filmmaker, slightly later in his career. It’s true that there was a little bit of George Romero‘s Night Of The Living Dead sprinkled in, among other things, but a much larger influence was Howard Hawks and, more specifically, the film Rio Bravo. Aware that nobody was likely to buy a Western at that period of time, but that he could easily sell an exploitation flick, Carpenter set out to write somewhat of an updated modern version of the film set “in the ghetto, in Los Angeles.” He’s also stated that the Assault reflected his own history of growing up feeling trapped in Kentucky and never fitting in.

Now, imagine if things had been slightly different and the timing was right for a good solid Western feature. Reaching back even further into his career, you would discover Carpenter‘s very first real film project, The Resurrection Of Broncho Billy, a 10-minute Western from 1970 that won the academy award for “best short subject.” John co-wrote and edited the short, but most importantly, he composed the music, which consisted of some fine western acoustic tunes, complete with finger-picking. Another thing that you may not be aware of is that his father, Howard Carpenter, was a music professor at Western Kentucky University, principal violinist of Nashville symphony, and appeared on recordings by legendary artists like Roy Orbison and Patsy Cline. Two of the primary reasons that John created the music for Assault as he did was because of the nature of the film and because of budget restrictions. But what if he was given the budget, the soundstage, and the clearance to create any type of film that he wanted? Would he have produced and how would that have informed everything else that he created afterward?

While his success with Halloween helped put his name on the map, it also resulted in him being viewed as a “horror director” to a certain extent, as well as someone who should be expected to produce magic from an extremely limited budget. We can’t know what would have been if The Thing was appreciated as the masterpiece that it was when it was first released, or if any number of other events would have yielded slightly different results. All that we do know is what happened. We know that John Carpenter made it a habit to take whatever ingredients and situations he was presented with and spin them into nothing short of gold time and time again. He retained creative control of his projects and went on to inspire countless filmmakers and artists that are working today, while his soundtrack work has continued to provide a blueprint for a very specific genre of music, whether anyone even recognizes that he’s the man behind it, or not. Seeing him up on stage at the age of 68, performing with his son, while his life’s work projects behind him, he seems pretty content with the life he’s achieved and it’s something to admire.