POWER AND SACRIFICE — MICHAEL GIRA Live @ The Triple Door [Seattle]

A review of the legendary Micahel Gira’s (Swans, Angels of Light) recent solo acoustic performance in Seattle with a brief rundown of his history

Michael Gira

The Triple Door

Seattle, WA

3/22/2012

“He reminds me of a dream I had where I was a murderer.”

It was partway through Michael Gira’s late-March set when Monsterfresh founder/editor Dead C said those words to me, and, goddamn, how perfect. I mean, really, there’s not much else to say after that. Without even realizing it, Dead C summed up, not only Michael Gira’s performance, but Michael Gira’s entire career in a one fell swoop, and a succinct one at that. I’m still in awe.

THE BACKDROP

Michael Gira founded SWANS in 1982. He was famously a teenage delinquent and runaway; he fled from his father while accompanying him on a business trip to Europe when he was 14. Gira spent that year working in Israeli copper mines, before logging a few months in a foreign jail. He returned to the US, dropped out of art school, and soon left his home in Los Angeles for New York City because, as he says with a smile in this 2011 video interview, “I think I saw Taxi Driver and I thought; ‘Wow, I want to be there’.”

Michael Gira founded SWANS in 1982. He was famously a teenage delinquent and runaway; he fled from his father while accompanying him on a business trip to Europe when he was 14. Gira spent that year working in Israeli copper mines, before logging a few months in a foreign jail. He returned to the US, dropped out of art school, and soon left his home in Los Angeles for New York City because, as he says with a smile in this 2011 video interview, “I think I saw Taxi Driver and I thought; ‘Wow, I want to be there’.”

SWANS came from that dark place, that place that spawned the violent, steamy, grimy Taxi Driver. The band’s early albums and EPs were exercises in torture . Albums like Filth and Greed, and songs like “Raping a Slave” and “Weakling” were smashing, bellowing, tinnitus-inducing wrecks; monotonous sheets of distortion and feedback, wherein Gira’s sore throat moaned haikus about sex, pain, and corruption against the oppressive backdrop of impossibly loud bass guitars and tape loops. “It was meant to be like a boxing match, except that I hit myself in the face,” Michael has stated of SWANS early sound.

By the mid-1980s, SWANS had added some new members, including Jarboe, a former female bodybuilder whose nearly operatic voice proved to be a near perfect sensual foil to Gira’s baritone. SWANS began a slow shift away from the bludgeoning atonality of their earlier releases with 1987’s Children of God, an album that married the grimy bitterness of their No Wave beginnings with more goth influence and tones. From this album forward, SWANS began to write songs, actual songs; songs about failure and remorse, but told through the more delicate means of hammer dulcimers, synthesizers, and multi-tracked guitars.

This was the era of SWANS that I first heard and this was the era of SWANS that I fell for. Their 1994 album The Great Annihilator hooked me and, even as I went back and heard the band’s earlier material, as it forsook all melody in favor of punishment and despair, I couldn’t help but see their entire career through a more human and more passionate prism–a prism that was overwhelmingly about fear, obsession, loneliness, but was tempered with a beauty, a longing, and a hope.

The Great Annihilator is easily SWANS most accessible album — it’s the sound of red hues, Sonic Youth guitars, and chiming bells. The first song, a two-minute keys/drums/guitar instrumental, ends with an extended sample of a blustery windstorm, followed by twenty seconds of a laughing infant. From there, the songs explore darkness for another full hour. Their swaying, bleary-eyed sadness was tailor-made for chilly winter months, borderline unhealthy introspection, and four o’clock sunsets. The album is brooding and gothic, but its songs are strikingly complex and mature. There’s a sophistication to the self-loathing of a track like “Killing For Company,” a song that mines the well-worn territory of a serial murderer, but concentrates on his brooding ennui and need for connection rather than the intimate details of his crimes.

The Great Annihilator is easily SWANS most accessible album — it’s the sound of red hues, Sonic Youth guitars, and chiming bells. The first song, a two-minute keys/drums/guitar instrumental, ends with an extended sample of a blustery windstorm, followed by twenty seconds of a laughing infant. From there, the songs explore darkness for another full hour. Their swaying, bleary-eyed sadness was tailor-made for chilly winter months, borderline unhealthy introspection, and four o’clock sunsets. The album is brooding and gothic, but its songs are strikingly complex and mature. There’s a sophistication to the self-loathing of a track like “Killing For Company,” a song that mines the well-worn territory of a serial murderer, but concentrates on his brooding ennui and need for connection rather than the intimate details of his crimes.

It was from here that I sought out the rest of Michael Gira’s catalog, from the rest of SWANS output to the albums he released with Angels of Light, a more pastoral, yet no less intense, group that he started after SWANS‘ demise in 1997 (the band reformed in 2010, releasing My Father Will Guide Me Up a Rope to the Sky later that year). Over time, the more I listened to SWANS albums like White Light From the Mouth of Infinity or Angels of Light records like Everything is Good Here / Please Come Home, the more that I realized that there was a real brilliance to Gira and to his work. With so many releases (at that point, ten SWANS studio albums, nearly an equal number of live releases, and six Angels of Light records, one a split with Akron/Family), it wasn’t so much a brilliance of execution and collaboration as it was a brilliance that came from honesty and humanity. Simply put, the more time that I spent listening to Michael Gira and his partnerships, the more that I felt like I was hearing him, and him alone. There was an honesty and a humanity to these songs. The albums were fearless and showed a disregard for placating an audience, any audience, even his own. Maybe they were overlong, but there was never any pandering heard in these songs, and it was impossible to hear anyone straining for approval or accolades. No one can dispute the intensity and flawless execution of songs like SWANS‘ “Where Does a Body End?” or Angels of Light‘s gorgeous “Not Here/Not Now,” but what is most impressive isn’t so much the grandiosity of these songs, but rather their sense of purity and intimacy. Amidst the density of the recordings, with their overdubbed instrumentation and, in the case of “Not Here/Not Now”, harmonized singing, there’s an undeniable quality in Gira’s voice; a tone that’s both confident and vulnerable, and one that covers a broad emotional spectrum. His baritone ruminations on death and sex are delivered with an aggression, a confrontation, and a nakedness, all at the same time. There’s an overriding gallows humor to his voice and a glint of winking, self-awareness that sneaks through, as if he delights in the gravity of his words. It’s this quality that filled me with a sense of joy and excitement like few other artists can. Time and time again, he managed to capture the futility and fatality of our human existence, and he did it with this sense of forthrightness and – dare I say – levity. His songs could be violent and lonely, and they could be surprisingly tender and loving, but they were above and beyond universal. They were about him, sure, but moreover they were about the human condition.

THE SHOW

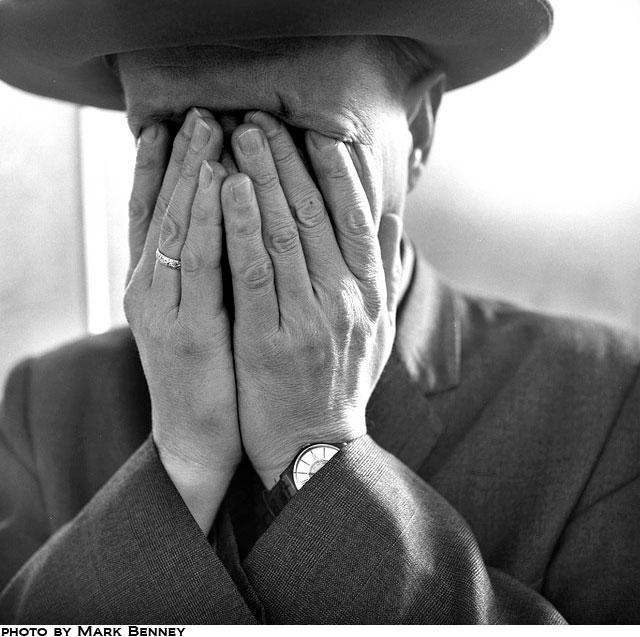

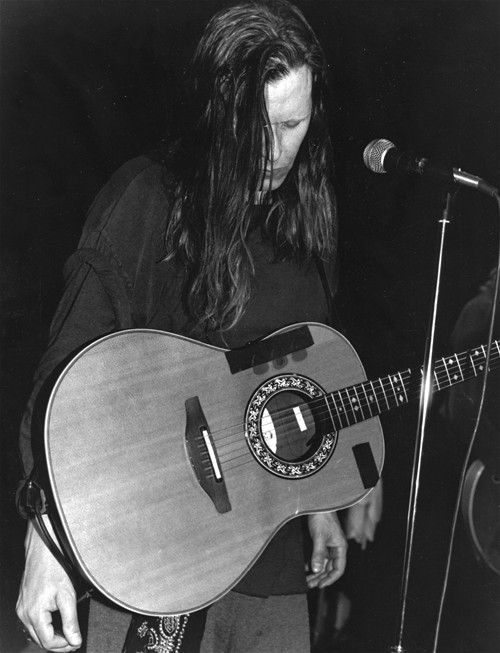

Michael Gira walked onstage at The Triple Door, clad as he always is and, quite possibly, always has been: like a Methodist preacher, complete with cream-colored Stetson, starched white shirt, and suspenders. He introduced himself, “Hi, I’m Bad Blake,” and took a seat. Exhaling, he grabbed his guitar and remained silent.

For five seconds.

For ten seconds.

Fifteen.

And then he began.

“Jim” was our opener. It’s an early track on SWANS‘ My Father Will Guide Me Up a Rope to the Sky. Performed acoustically, it was stripped of its sense of beauty and imbued with a greater sense of immediacy and melancholy. Without bass or drums, “Jim” showcased the dramatic and commanding presence of Gira‘s voice. The song itself wasn’t strikingly different from how I’d heard it on the album — it’s structure, tempo, and chords were the same — but it had a new intensity and a new focus. The lyrics about “methadrine teeth,” “burning cities,” and “walk[ing] barefoot on this carpet of air“ were now at the forefront. They came across as more cynical and humorous than I’d noticed before, and Gira managed to re-create the album’s crashing cymbal-laden choruses with nothing more than his voice and the acoustic chords he strummed with the tip of his thumb.

“Eden Prison,” the second song of the night was equally as confrontational. Another track from SWANS’ 2010 album, it was clearer, more uncomfortable, and delivered with more force in this acoustic rendering than in was as a full-band and full-bore recording. Gira delivered the song with spite — lyrics like “he would gladly rip the throat from God if only he could reach up to his white ass” sung and spoken as if through clenched teeth. The song’s extended bridge was a single chord, hammered away for a droning eternity and was no less effective or affecting than what could have come from a thundering backing band.

It was somewhere around here that Gira made a request into the mic for even more volume. Songs about “not being able to breathe…especially when you’re being choked by your own bad habits,” songs that alternated lyrics like “go suck his cock now, go feed your thirst” with lines like “in your mouth I tasted beauty,” and songs from twenty years prior that called the future a “cold thing in the damp ground” were elevated to a grand and inescapable status when the monitors were turned up. As counter-intuitive as it seemed to crank a solo acoustic performance to these levels at first, it was quickly shown to be a perfect and necessary decision. With added volume, Gira’s voice and his spare chords where treated with respect, and they were given the weightiness they deserved. There was a confrontational and enveloping aspect to it all – it was impossible to turn away, to avoid, or to concentrate on anything else. It forced you… me… us to accept the wailing intensity of “She Lives” and “The Promise of Water,” and to accept them for what they were. They may have been about the darker realities of life, but when they were performed for us in this venue and in this manner (acoustic, unaccompanied, loud), they were somehow less intimidating and somehow more life-affirming.

There was something noble and invigorating about this approach. Gira was completely unapologetic and his confidence overrode any sense that you might have of his material’s dour catharsis. He wasn’t oppressive and he wasn’t exhausting. Hearing him stretch out syllables and watching him tap his foot and close his eyes, was a way to see him as a person and artist. It took away the intimidating mythology that his recorded output suggests. Between songs, he was conversational and engaging, introducing a tune that would appear on an upcoming SWANS album as being “too good for me to sing” and asking the front row if “one of you, maybe you, could go get me a beer from the bar.” [This new SWANS song, incidentally, featured a delicate and poetic line about “conquer[ing] this land on a horse made of clouds” and concluded with a call to “destroy, destroy” before quietly ending with “then begin again.”]

There was something noble and invigorating about this approach. Gira was completely unapologetic and his confidence overrode any sense that you might have of his material’s dour catharsis. He wasn’t oppressive and he wasn’t exhausting. Hearing him stretch out syllables and watching him tap his foot and close his eyes, was a way to see him as a person and artist. It took away the intimidating mythology that his recorded output suggests. Between songs, he was conversational and engaging, introducing a tune that would appear on an upcoming SWANS album as being “too good for me to sing” and asking the front row if “one of you, maybe you, could go get me a beer from the bar.” [This new SWANS song, incidentally, featured a delicate and poetic line about “conquer[ing] this land on a horse made of clouds” and concluded with a call to “destroy, destroy” before quietly ending with “then begin again.”]

It was the lighter moments like these that make me a Michael Gira fan and have me anticipating his every next move. They make me want to revisit his catalog and regret that I missed SWANS’ most recent tour. There’s something visceral and real about his music and his performance, and there’s something both primal and everlasting in all of it -almost like a constant push and pull between the Blood and Honey of life. For all of the references to hatred, cowardice, and “a violence that’s pure and clean,” and for all of the buzzing strings, dirge-like pacing, and barking and bellowing, there’s a delicacy and corporeality to it. There’s stillness and moments of sheer beauty, and when Gira strings together a line about a “poem on your porcelain white back,” it’s a moment that not only offset the darkness that surrounds it, but that serve to put that darkness in a different light. It’s in these moments that the character and levity of these explorations and suffering and struggle are invigorating rather than depressing. There’s a beauty that emerges in this brutality, an honesty and a confidence that is intriguing and powerful.

The songwriter closed the night with “God Damn the Sun,” a song from SWANS’ 1989 album The Burning World, a miserable, despondent, suicidal song about loss and alcoholism, if there ever was one. But, in spite of its melancholy and melodrama, there’s a truth and reassurance lurking within it. It comes from a dark place, but it doesn’t need to be explained and it doesn’t need to be defended. The fact that it exists without a greater context is what makes it real, what makes it personal, and what connects us to Michael Gira and to one another.

It was during “Blind,” arguably Michael Gira’s best song, that Dead C told me about his dream. As the second verse came off stage, and as he leaned my way and said, “This reminds me of a dream I had where I was a murderer,” he took a single, lone beat and followed it with:

“It was a good dream.”

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Setlist:

Jim / Eden Prison / Oxygen / She Lives / Blind / On the Mountain (Looking Down) / Two Women / My Birth / Promise of Water / Song for a Warrior / My Brother’s Man / Encore: God Damn the Sun