Songs In The Key Of Life: Interview with THE GOOD ONES Producer, IAN BRENNAN

When we mention “two-time award nominated producer, Ian Brennan,” a good percentage of mainstream America would likely assume that we were referring to the creator of the FOX network’s musical sitcom, GLEE. We aren’t. Although his work may be less recognizable among the soccer mom and mall-frequenting tween sets, the Bay Area producer/musician/writer/indie-promoter is, arguably, much more prolific than his prime-time Hollywood namesake. [Please note that this is not a claim that Brennan is likely to make himself, or one that he is even likely to concern himself with.]

Through various successful ventures, Ian has consistently proven himself a modern day Renaissance man, drawn to any project or cause that he finds substance in and feels that he has the ability to be beneficial towards. Besides working on his own music, Brennan produced the debut release from Rain Machine (aka: Kyp Malone from TV on the Radio) in 2009, and has received Grammy nominations for his work on albums for both Rambling Jack Elliot [I Stand Alone -2006] and Peter Case [Let Us Now Praise Sleepy John – 2007]. He’s been a highly successful concert promoter- raising over $100,000 in charity funding from benefit shows- and booked the music for the free “Food Not Bombs” 20th anniversary show (feat. Fugazi and Sleater Kinney). Over the last 17 plus years, he has worked as an expert on the subjects of violence prevention, anger management, and conflict resolution (both as a published author and lecturer) and, in 2008, created San Francisco‘s Sidewalk Homeless Memorial, raising awareness for the numerous casualties that annually befall individuals who are living on the streets. Brennan has worked in public radio, written a music column, directed a weekly public-access TV show, and even created the original “Boxing Bush” online video game, after unsuccessfully extending a challenge to the former U.S. President to compete against him in an 8-round charity boxing match. For his latest project/labor of love, the Bay Area-native has focused his sights overseas and unearthed the soulful music of a relatively unknown Rwandan trio known as The Good Ones. At a time when bad musical theater renditions of 80s covers by Twenty-something actors posing as precocious teens are being credited with breaking Billboard Top 100 records held by the likes of The Beatles (who they cover!), James Brown, and Elvis, music this unpretentious, pure, and untainted by over the top marketing gimmicks is more essential than ever.

Brennan‘s journey in Rwanda began when he accompanied his wife (filmmaker, Marilena Delli) and the film crew for “Rwanda’ Mama” in documenting his mother-in-law’s first return to her birth country in 30 years. After witnessing her family’s rape/murder during the first Rwandan genocide back in 1959, Marilena‘s mother was orphaned at the young impressionable age of only 7 years old. In 1978 she married an Italian ex-priest and relocated to Italy, only to endure additional issues of poverty and racism in a completely new environment, with the added setback of an unfamiliar language. The subject matter of the film is intense and, throughout the course of her return visit, she is even reunited with her best friend, whom she had previously believed was slaughtered in the 1994 massacres. In addition to the focus placed on her mother’s return home, the film also addresses feelings of displacement for Marilena and her sister, who were persecuted as “blacks” in Northern Italy, and the disillusionment felt as they realized that they would find no more of a home in Rwanda, where they were viewed as “white” outsiders.

Ian spent his time in Rwanda on his own personal mission to discover hidden musical talent in a nation overshadowed by the trademark sounds of such neighboring countries as Burundi and The Democratic Republic of Congo. This quest was further fueled by a need to disprove so called World Music “experts” and their close-minded claims that Rwanda had absolutely nothing of value to offer the music world. The producer held a firm belief in his vision but, after two-weeks of intense searching, he was still coming up flat. It was at this point, in July of 2009, that he was introduced to the inspiring musical harmonies of The Good Ones:

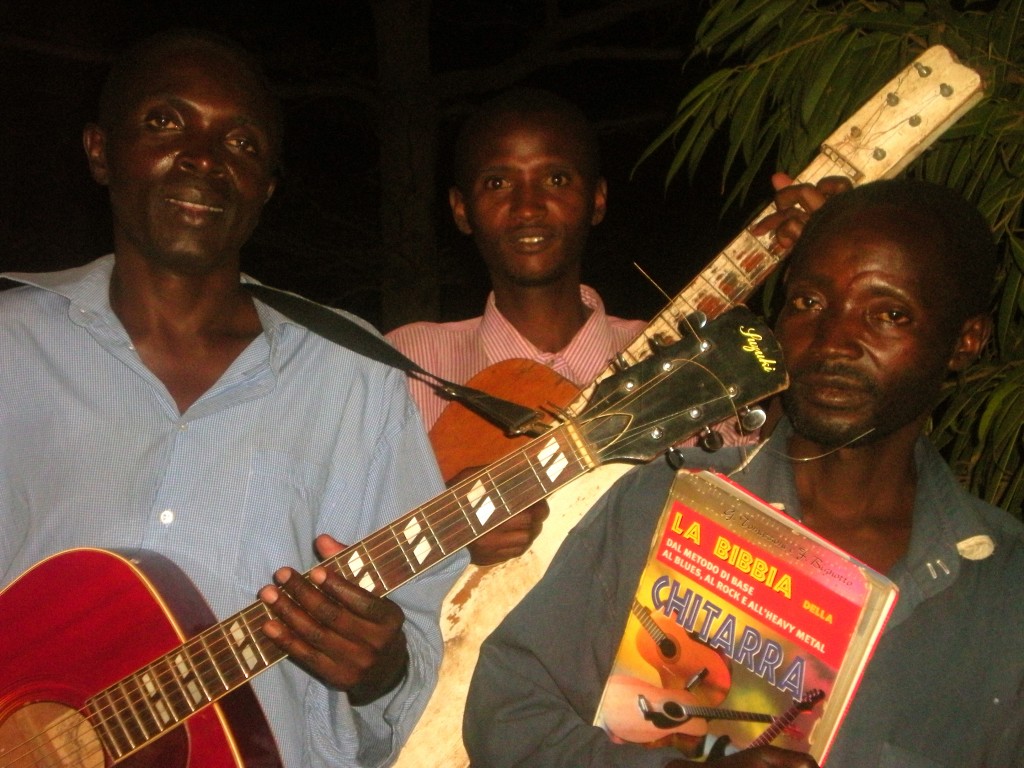

“They were standing in the dark, their eyes downcast and restless, and holding only one guitar between them. From 100-feet away, I knew instantly that there was something special about them, a feeling one is lucky to experience even once in a lifetime. By that point, I’d already visited literally every recording-studio in the capital (Kigali) and surrounding areas over two weeks and listened to hundreds of artists, but to no avail. This meeting had been set up through a mutual friend and the instant the band opened their mouths to sing, it was as if the universe reached down to tap me on the shoulder and say, ‘What these guys do is precious and rare. Don’t fuck it up.‘”

That first night’s meeting was with Adrien Kazigira (47 yrs old) and Stany Hitiman (also 47), only two-thirds of the group, and the one guitar that they wielded between them contained only two-thirds of it’s strings. Even with this lesser format, Brennan knew that he had finally found the artists that he’d been searching for. With the aid of a translator, he urged the duo to allow him to document their sound. They agreed, but assured him that they were only a shell of themselves without their final member, Jeanvier Havugimana (38). The following night they returned as a trio and an additional, although battered, acoustic guitar was located for Kazigira, while Stany played the 4-string. Brennan constructed a makeshift recording set-up by utilizing a couple of condenser mic’s and elements from the documentary crews video cameras. What resulted was the beautiful and intimate 11-track release, Kigali Y’ Izahabu, released by Dead Oceans last November.

Recorded outside on the porch of the very same property that they had met at the prior evening, Kigali Y’ Izahabu is as raw as it is moving (on the song, “Umahanano” wild dogs can actually be heard barking in the background). The vocal harmonies are misleadingly complex, as they commingle and whirl like dervishes; filling the gaps in the guitar lines like breezes effortlessly swirling through forest canopies. Over time, World Music has often become as diluted as any other genre of music, and The Good Ones remind us of the value that can be found within other cultures, no matter how foreign they may seem to our own. Not even recorded in straight-forward Kinyarwandan (the official Rwandan language), but rather in a street dialect that not everyone in their home country even understands, Kigali Y’ Izahabu communicates through it’s emotions, delivery, and tone as much as through the words themselves. I haven’t been as instantly affected and struck by the sounds of a “world music” album in this way, since I was introduced to the kora through Toumani Diabate‘s 1988 solo debut, Kaira. More than just a testament to what outside cultures have to offer, The Goods Ones are a reminder of both the purpose and possibilities of music, itself. With a group comprised of 3 middle-aged war veterans/genocide survivors who subsist on next to nothing in one of the poorest countries in the world, these men do not play music for any other reason than because their souls have instructed them to do so. Considering their circumstances, the idea of getting a record deal wasn’t even on their radar, let alone a priority. With all of the press releases we receive from groups with slick marketing campaigns, high-budget videos, and appropriated imagery, the honesty behind these 3 Rwandan men is both welcomed and refreshing. And, with all of the newfangled titles being invented to fabricate the illusion that some entirely unique new genre like “Post-Wave-Core” (TM) has been invented, I don’t know how else to refer to what The Good Ones present than to simply call it “MUSIC”.

We have been fortunate enough to communicate with Ian Brennan, himself, and have the producer discuss with us a bit more about his process, perceptions, and over all experiences in working on this amazing project. That dialogue of that conversation is posted below. We hope you enjoy it.

MONSTER FRESH: I know that when you headed to Rwanda it was partly for the filming of Rwanda Mama, documenting you mother-in-law’s return to her birth country. How long had you been intending to search out Rwandan music prior to that? Was it something that you had been hoping to do for a long time or more of an idea that you began fostering once you knew that you would already be heading to the country with your wife?

IAN BRENNAN: The music search was an idea that formulated once the trip was scheduled and developed further while we were there and became more acquainted with the country.

From what I’ve read about the documentary, it seems to address strong elements of racism and prejudice, but I was surprised to hear that there is so much prejudice against the MUSIC of Rwanda, as well. Did you find your own quest of redemption aligning with the progression of the documentary at all?

The documentary and the record are definitely related. The record would not have happened without the documentary.

I’ve noticed that a film still from the Rwanda Mama site is also being used as the cover art for The Good Ones’ album and am wondering if that is the extent of the integration between the two finished projects.

They are separate entities. Hopefully, they both help bring positive attention to Rwanda, a diverse country of almost 10 million people. Rwanda’ Mama, ironically, features much great Rwandan music (a lot of it rarities from the 1970’s), but not The Good Ones.

The photos were done by Marilena and her sister and the video footage by Marilena, so thanks to them we have strong visual components for the project.

You’ve stated that there are political issues discouraging street musicianship in Rwanda and that it was something which made seeking out the local music more difficult for you. You’ve also referred to The Good Ones music as part of a tradition known as “Street Songs”. Was there once a strong street music element to the culture and, if so, approximately when did that end?

In our experience there were no street musicians and we were told by more than one person that it is discouraged there, but i do not know officially what the status of that is. The “worker song” tradition is a folk tradition and when they speak of the streets it seems that reference is more regarding the “tougher” neighborhoods than actually performing publicly.

Stylistically, is the tradition that The Good Ones music stems from something that is still vibrant in the country or is it a sound that is near extinction due to abandonment by younger generations?

Rwanda is musically diverse and vibrant, but in our experience most of the music currently being made there was akin to American hip-hop and R & B, but with Kinyrwandan lyrics.

It seems like you had a goal to prove that Rwanda had something important and valid to offer the world musically, but when you went there, you had such difficulty locating anything of substance. Do you feel that The Good Ones are ultimately a representation of Rwanda, simply a singular musical anomaly of a few individuals creating magic, or, at this point, does that even matter?

They are individuals. Rwanda is a complex and rich culture of almost 10 million people. There is definitely something magical and unique about the music these three men make, though.

This is basically just an extension of the last question but, coming from a country with such a loaded history, how important do you think it is to focus on the musicians as individuals vs where they are from? How much importance do you place on the arts to create understanding and compassion between cultures?

Art is a great commonality and can transcend race, nationality, class, with amazing ease. It can be one of the most powerful gateways for creating understanding and compassion. Certainly, Dr. J or Jackie Robinson or James Joyce or Bruce Lee, did more for lastingly breaking down stereotypes and barriers between human beings than any politician could ever hope to.

The arts both reflect and for better or worse lead a culture. Rwanda deserves much recognition beyond the tragedies of the genocides.

When you met them that first night and they explained that they needed their third member to record, did you feel an urgency where you felt like you might lose the opportunity if you didn’t record immediately?

It was definitely a bit scary to wait, particularly since Stany and Adrien also harmonize quite well together. But they were definitely right that it was even better with Jeanvier.

[vimeo]http://vimeo.com/15170516[/vimeo]

In the song “Gahinda Umpora Iki We” (“Sadness why do you persecute me?”) there is mention of the song Bertilde being stolen in the lines, “I wrote the song about Bertilde. The morning after they stole it from me. They put it on CDs and on DVDs.” Did they explain that scenario in any more detail and how trusting and open were they to allowing you to record them, overall?

They definitely were wary. The tradition of bootlegging is so predominant in Africa and most regions outside of North America, Japan, and Europe, that there basically is no official or legal record industry in much of the world.

There is such a variety to the subject matter from song to song, but much of the lyrics deal with concepts of universal wisdom. I like that “Gahinda Umpora Iki We” lends a balance to that subject matter, demonstrating that even these men, who seem to have such a firm centered grip and uplifting view on everything, still have their own moments of fear and doubt. “Umuntu Ni Nkundi” (“One person is like another”), however, seems to encompass more of the general tone of the album, because they don’t seem to be complaining about their circumstances, but rather, just understanding and seeing beyond them. Based on the time that you spent with them, do you find that to be an accurate interpretation of their characters?

It seems that very few people in Rwanda have not directly been touched by unthinkable tragedy, so there is a palpable depth and sadness melancholy that underscores most interactions, but also a mature joy.

It’s my understanding that for the translations, you’re mother-in-law first had to translate the songs from an informal slang to Kinyarwandan, then to Italian and, after that, your wife translated them from Italian to English. Did you have any idea what they were singing about when you were recording? Was there any pause for explanation or did you just go straight through the recordings with little interaction?

Certainly there was an element of wanting to be sure that we knew what was being sung about and the quality of the lyric writing was another great revelation. We did know that the vast majority of the songs were love songs as evidenced by 4 of the 12 titles being names of women.

Much of the content is universally relatable, like how “Ibyʼisi ni Ubusa” (The things of this earth one day or another will end) is about the impermanence of materialistic goods or how “Bakame nʼ Ingwe” (The fox and the leopard) addresses the pain of deceit and infidelity. For me, “Egidia” is a bit more difficult to discern the meaning behind and I was hoping that you may be able to enlighten me about it. I wasn’t sure if it’s just a simple story about a girl moving away without a trace or if there was anything more to it culturally that I would be missing.

My understanding is that often in Rwanda communication channels are difficult, so the poignancy of losing contact with someone can be quite deep. For instance, my mother-in-law lost contact with her best friend for decades and had believed her dead, before discovering in 2008 that she was still alive.

As a successful public speaker on the subject of Anger Management, I am curious about your interpretation of the song, “Amagorwa yʼ Abagabo” (The desperation of men).

It is certainly one of the more controversial lyrics, but i think its largely redeemed by the final stanza.

[audio:http://monsterfresh.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/04-Amagorwa-y_-Abagabo.mp3]“Usually some men have a difficult life

Usually some men have a difficult life

But there are some women who have a difficult life too

Try to speak…what do you say? If you speak, I come and beat you

Try to speak…what do you say? If you speak I come and beat you…

But not everyone is like that…”

Since there are limited forums for them to perform in publicly or as a “band”, I was surprised by how structured and well formed their songs were. Do they consider themselves to be a formal group or just some friends playing music together?

They do consider themselves a formal group, but there are few venues for public performance in Rwanda.

Did you expect them to have so much material available from the beginning or were you surprised to find that they had such a large catalog to draw from? Also, had you even intended to find that one group or did you expect to piece together more of a selection from different artists initially

It was a journey and quest with no real end-goal in sight, just the hope and faith that there would be much great music out there. The depth of The Good Ones’ writing, particularly Adrien’s, is rare anywhere. It has been gratifying to defy the “wisdom” of more than one of the European colonialist music-industry figures who act as the gatekeepers for bringing international music to the world and had the audacity to tell me, “Rwandan music is not good.“

I know that they cut the recording session shorter than you had hoped, because of a “meeting” the next day. Are there hopes to record more of their work at some point?

It would be nice to record more. And they certainly have much more material, some of which I heard (and was as strong as most songs on the record) and most of which i didn’t.

One of the first questions that I had regarding the unique nature of an album like Kigali Y Izahabu, relates to the concept of “production” versus “documentation”. Then I found a comment from you stating that you view every album that you work on as a “field recording” on one level or another. Producers are typically acknowledged for the signature touches that they put on an artist’s sound but, with something like The Good Ones in particular, the approach seems to be to avoid and/or remove as many fingerprints as possible. How much does the approach to recording differ on an album like this and what, if anything, did you take away from it that might lend itself to your overall approach to recording in the future?

Hopefully, every experience is a learning process. I view my job as trying to be as objective, invisible, and and ego-less as possible, and hopefully to help artists get out of their own way and not be tripped up by their own subjectivity. For example, almost every artist I’ve ever known hates the song that is most beloved by neutral listeners.

In the interview with SFist.com you talk about your approach to working with an artist by stating that it is “More than getting them to do something, it’s getting them to not do something.” Were The Good Ones extremely organic with the process, seeing as they don’t generally encounter a situation such as this, or was there any hesitation or issues of them trying to deliver something to you that they thought you may have wanted?

They were very professional and focused. they played Sara three times– once the first time and twice the night of the recording– and all three times it was uniformly stellar. In my experience, in the absence of TV, video-games, etc. many African communities have deep practice of self-entertainment where expression musically is a normal part of daily life.

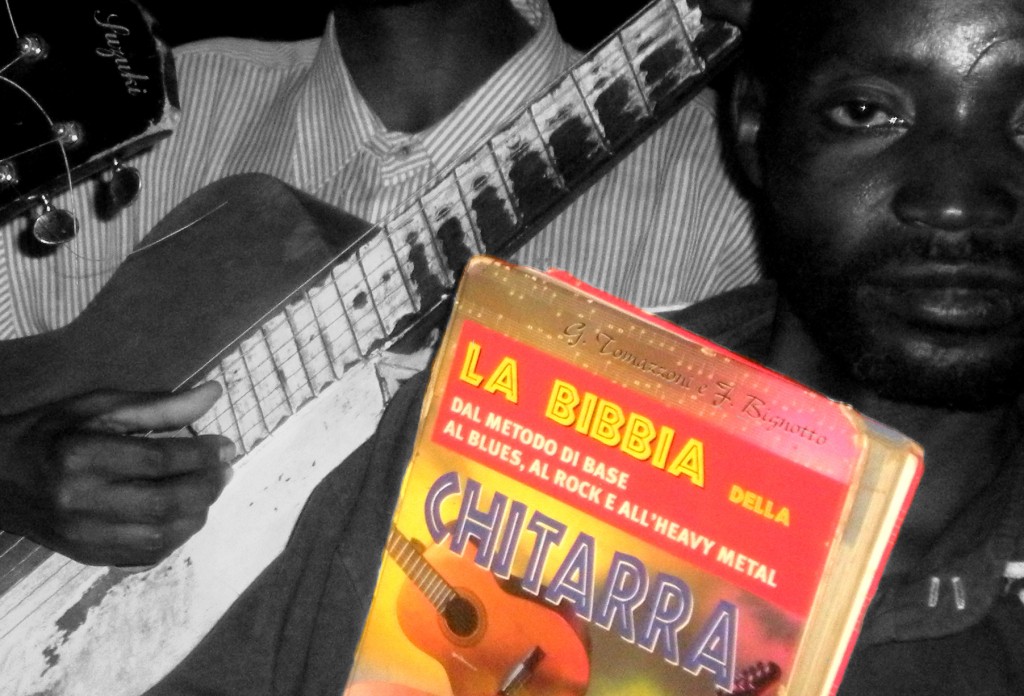

In the promotional images Jeanvier is holding a book labeled “Chitarra”, is that where they learned to play?

Stany is holding the book. Its an Italian song book and he said he used it to learn many songs and was quite smitten with Italian culture from what he said.

You’ve been associated with Anti- records in the past; what brought you to Dead Oceans for this release?

Bob van Heur, a great independent promoter in the Netherlands, suggested that i contact Phil at Dead Oceans. I was immediately impressed with how instantly Phil had an understanding of what made the band special– the deceptively complex vocal interplay, etc.

What’s the next step? How much post-nurturing takes place with a project like this?

The next step is hopefully that they can tour Europe and/or the USA, but there are many bureaucratic elements that impede that. Also, hopefully the record will find a place in the canon of “world music” and enjoy the longevity it deserves (and hopefully also provide greater financial rewards for the band).

It’s been an ongoing labor of love, but a pleasurable one. The more people that hear the record, the greater the benefit, i think for both the band and the listeners.

Before ending this, I wanted to give you an opportunity to tell us more about your new book “Anger Antidotes: How Not to Lose Your S#&!” which is coming out this year.

It’s been over 17 years in the making. There are many books on the subject, but hopefully there are a few insights in this one that will help a few folks to find constructive alternatives to the negative behaviors we see around us so often.

BUY Kigali Y’ Izahabu HERE

And make sure to check out the following links:

IAN’s Official Website

The Good Ones (on Facebook)

The Good Ones (official Dead Oceans Artist Page)