No Plan B – MARC MARON Live @ the Neptune [Seattle]

A breakdown of comedian/podcaster, Marc Maron’s career and a review of his first solo theater performance, held @ the Neptune Theatre in Seattle

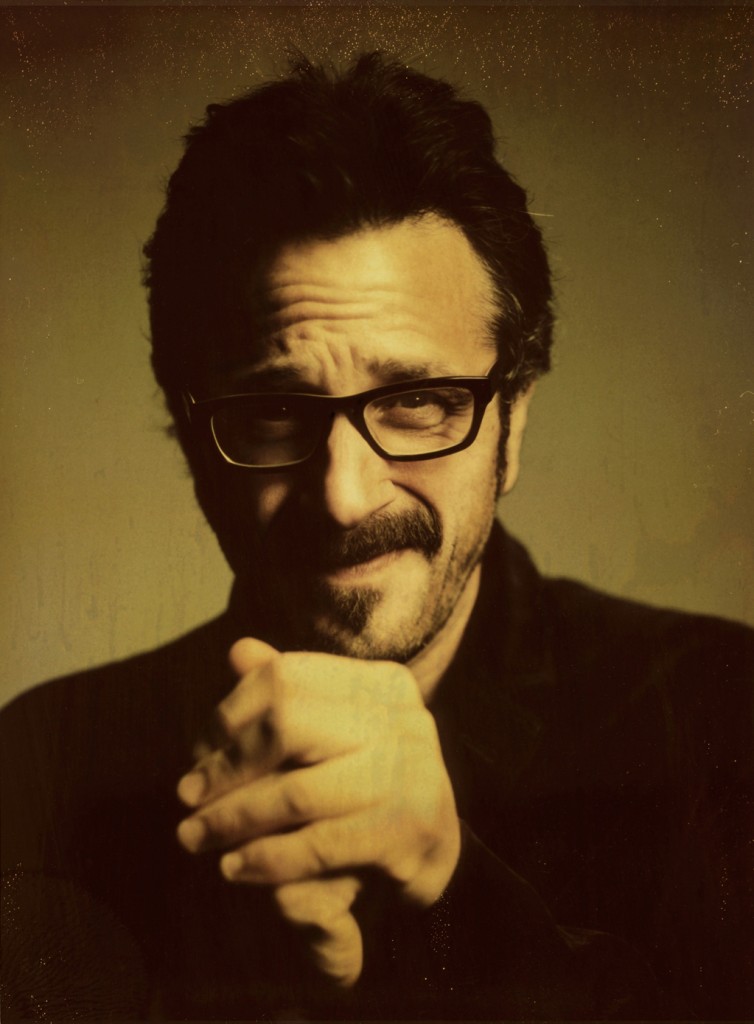

Marc Maron

Neptune Theatre

Seattle, WA

11.25.11

So you’re probably thinking, “Jesus Christ, Devon. What the fuck? This goddamn show was, like, two months ago. What the hell took so long?” I know. I understand. I’m a little upset about it all myself. But here’s the thing, see… it’s Marc Maron. I love the guy, I really do, but sometimes he can be a little rough for me. Not him or his material per se, but the thing is that, when I talk about Marc Maron, or when I think about Marc Maron, I can’t help but think about myself. I can’t help but think about how I think about myself, how much I do, and why and when. Once I start getting into self-examination like that, well, it can get a little overwhelming, and it can get a little paralyzing. But at the end of it all, it’s why I love Marc Maron. It’s why I’ve listened to all two-hundred forty-something episodes of his podcast. It’s why I bought all four of his stand-up records, and why I’ve read his book more than once. It’s why I snagged a ticket to 2010’s Bumbershoot festival, just so that I could see a live taping of his podcast. It’s all because I know that I should look inside myself – I want to and I feel like I’m ready to- and it’s not something that I was ever compelled to do before I got into this one stand-up comedian.

Marc Maron has been doing stand-up for over twenty-five years. He’s been on my radar since junior high, back when I’d come home from school and watch whatever was on the then-nascent Comedy Central. Every day I’d listen to In Utero, drink Dr. Pepper, and watch clips of stand-up comedians on Stand-Up Stand-Up and Short Attention Span Theater, a clip-show that Maron briefly hosted in the early ‘90s. For years after that, I’d occasionally flip by Marc Maron’s half-hour Comedy Central specials on television, and his name always popped up in conversations I’d have with my other comedy-nerd friends – one of whom would make a point to see him on his unbelievably frequent appearances on Late Night with Conan O’Brien (the comedian has performed over forty times on the show). Marc co-hosted Morning Sedition on the defunct left-wing talk-radio station Air America and I can still remember a close friend telling me that the only way that he could listen to the show was to get up in the middle of the night and stream the East-Coast feed over the internet. It was something he did as often as he could.

When he was coming up in the 80s and 90s, Marc was part of the Alternative Comedy movement. His shtick wasn’t about sport coats or “Do you ever notice?” Seinfeldian musings. Maron turned his comedy inward. He was unique because when he got up on stage he talked about things that happened in his life; the same painful and self-critical things that exist in your own life, but that you probably didn’t even talk about with your own friends. It could get a little uncomfortable now and again, but it was always smart and always personal, even if it did hit upon rage and regret. The genius of all of it was that it wasn’t until the bits ended that you realized they were bits in the first place. They weren’t just stories or confessions like you thought, but they actually had structure and they actually had beats and punchlines, subtle though they were. Nothing seemed forced or egregious, it just seemed natural and intimate. You laughed because you “got it.” Maybe you were the same way. Maybe you yelled at someone like that or maybe you doubted yourself the same way. Maybe those same voices in your head tore you down the same way that they did Maron. Marc’s honesty onstage was what drew you to him, and it’s something that you had to be ready for.

During the late 2000s, Marc Maron was at a crossroads. It’s something that he’s often talked about in interviews and on podcasts, but to put it bluntly, his career was at a standstill. The radio gigs were up. The clubs were half-full. He’d been doing this for how long? He was how old? His 2009 double-disc album, Final Engagement (recorded in Seattle at the “renowned” Giggles comedy club) isn’t necessarily a depressing experience, but it most definitely isn’t an uplifting one. The comic veteran’s exasperation and frustration is on full display – he opens the record by referring to himself as a “marginalized act” and goes onto voice every concern about his future and faltering career to the audience. He says that people leave his shows saying one of two things: either, “That guy’s hilarious” or “I hope he’s okay.” It’s clear that something had to happen, and that something turned out to be WTF.

WTF is Marc Maron’s podcast, one that he started in September 2009. It’s early days were like this: Marc and a comedian friend sat down and talked for an hour. That was it. It started with some rants from the host talking into a microphone about his day, his insecurities, and his rage. From there he would swap road stories and career tales with a fellow comedian – maybe someone like Dave Attell or Kyle Kinane. I first heard about WTF a few months after it hit iTunes. I’d been heavily into podcasts for a few years and I was definitely interested in something new, especially something with comedians riffing and complaining. There were three months of WTF episodes available in the iTunes store and, as soon as I listened to Episode One, I knew that I’d found something goooood. It was like I’d suddenly stumbled onto a new group of friends; a group of clever guys reminiscing about their careers and deconstructing the art of stand-up comedy. I felt like I had a real connection with Maron, something that I hadn’t really felt throughout all of that time that I’d been watching him on television. On the podcast, he was even more open about his own life, so much so that it made me feel like I should be too. I could relate. He made me – just some chump listener – feel like he was a friend. I couldn’t stop smiling when he talked about something mundane, like how upset and embarrassed he was after he bought those boots that didn’t fit and then, how he felt like they were forever taunting him from the closet. I’d felt the same way about a handful of awful shirts that hung in my own closet. When he talked about loneliness with another stand-up I felt a certain kinship because I had those exact feelings too. And, even while I couldn’t relate to his stories about blowing up at a colleague or being a callow youth, there was an energy and a confidence in his voice during every story that made me feel like it was alright to open up about your mistakes and missteps. Sometimes Maron and his guest would get on a jag laughing about ‘80s stand-ups that I remembered watching on Comic Strip Live and I ached to be part of the conversation. During his on-air eulogy for Greg Giraldo – a stand-up who died of a prescription drug overdose in September 2010 – I heard Marc’s heartfelt sobbing and hurt and I nearly broke down myself. Months later, when comedian Greg Fitzsimmons was a guest, I came close to tears again; only this time it was because of how infectious and joyful it was to hear two friends – two guys who had come up together in the Boston comedy scene, decades ago – joke, laugh, and rib each other the same way that we all do with every one of our close friends. The purity and sincerity was undeniable and it was made all the more poignant because it felt like an ordinary green room hang-out session and not an episode of one of the number one-rated podcasts on iTunes.

So, anyway… now Marc was coming to the Neptune Theater. I knew that I’d be there. I couldn’t not be. But, as excited as I was for the show and to see one of the few comedians that I felt like I understood and related to, I was nervous. This was partly because it was Marc’s first solo theater show – his first time out of the clubs – and I felt a little nervous the way that you would for any friend who’s taking a big step forward. But mostly, I was worried, because I knew that I’d be in the Neptune alongside hundreds of people who felt the same way about Marc that I did. Hundreds of us would be sitting side-by-side and it scared me to think that this very show could mean the end of the illusion that I, and I alone, had a truly personal connection to Marc Maron. It scared me a little to think that Maron wouldn’t be mine.

I worried about who would be there and how this would affect my enjoyment of the show. I had seen Marc Maron perform at a suburban comedy club about a year earlier. There was a two-drink minimum and the feature act was a middle-aged Texan woman who did thirty minutes about how her boobs sagged and how her teenage daughter had a nose ring. What I remember the most about that night wasn’t so much that I sat at the lip of the stage or that Maron looked me right in the eye as he ranted about his notebooks and his cats, but that the crowd wasn’t “hip.” I remember looking around the club and noticing how many people – middle-aged and “regular” people – came out, not because they wanted to see “Marc Maron,” but because they wanted to see “comedy.” It fell on a Friday night and it was just something to do.

But now, I thought, we were just one year later and within that time WTF had exploded. Marc had been profiled in the New York Times and the Onion AV Club. His show had pulled high profile guests like Gallagher (who stormed off the show) and Robin Williams, Ira Glass and Brian Cranston. And we were in Seattle. Would there be a theater full of mustaches and skinny jeans? I was nervous that the person sitting next to me, the person sitting behind me, and the people sitting seven rows back would all be WTF-ers too, that they’d too know every detail about Maron’s life and had brought cookies and clever t-shirts for him. Most importantly, I was worried that there might be a collective sense of over-enthusiasm at this show and that it would weaken the connection that I felt I had with Marc, that I would be forced to confront the fact that I wasn’t the only one who felt that way.

Before the show, I wondered what it was that Marc would talk about. Would he have a new act? How new? How much would I know from the podcast? He just tweeted about shaving his mustache, I wondered if he’d have facial hair. I wondered if his girlfriend was there. I wondered if he’d talk about his cats Boomer or LaFawnda. I thought about that story that I’d recently heard on WTF about the raccoon that died under his house and whether or not that would turn out to be part of his act. I started feeling like I knew too much about Marc Maron.

At 9:30 it was time. We’d already heard a little AC/DC canned music pumped over the speakers and we’d seen the opening act. This was it. Maron walked out onstage. He wore black boots and had a 5 o’clock shadow. The facial hair was on its way back. He wore a blazer. He wore Levi’s. They were just like mine.

He opened his set by talking about the poster advertising this show. It was an homage to a famous Lenny Bruce poster, from when the legendary comedian had performed at San Francisco’s Fillmore Auditorium. Maron stood onstage comedy-nerding out about it, how flattered he was that someone had put him in such company, and also about how scared he now was that he’d have to try and live up to that mythology and legacy. Marc segued into a line about his own relationship with his audience and how his tendency is to harangue everyone in some sort of unconscious effort to push them away, pull them back, and then push them away again.

He opened his set by talking about the poster advertising this show. It was an homage to a famous Lenny Bruce poster, from when the legendary comedian had performed at San Francisco’s Fillmore Auditorium. Maron stood onstage comedy-nerding out about it, how flattered he was that someone had put him in such company, and also about how scared he now was that he’d have to try and live up to that mythology and legacy. Marc segued into a line about his own relationship with his audience and how his tendency is to harangue everyone in some sort of unconscious effort to push them away, pull them back, and then push them away again.

Maron talked about the Occupy Wall Street movement and read a snarky and accusatory email that he sent to his cousin, a high-class stockbroker that he hadn’t seen since they were adolescents, jamming on a Rolling Stones tune in a relative’s basement. Marc talked about his girlfriend and, in what was probably the most telling moment of this evening, he didn’t say, “My girlfriend and I” but rather, “Jessica and I.” He stood on stage, called her by name, and immediately followed that with an acknowledgement that, yeah… we all knew who “Jessica” was. We knew all about her and their relationship from the podcast. It was that one tossed-off line, “You all know Jessica” that meant a lot to me and seemed to sum up, not only the entire evening, but also where Maron is right now in his career and in his life. It was right then that everyone in the theater unconsciously realized that, when it came to Marc Maron (and especially to the post-WTF Marc Maron) that we all had a relationship with one other and with the man with the microphone standing before us. Even if we’d never met, we were somehow still pretend-friends. It was almost as if this one phrase had let us all know that there was no longer the same fourth-wall barrier between performer and fan. We all agreed, in one way or another, that we were there because we had something in common and because we had this weird affection for and intimacy with one another. Maron recognized this and it was at that moment that I realized that there really was unique energy and comfort in the air.

Most of the other bits I knew from the podcasts, and some I recalled from previous performances or from Maron’s most recent album, 2011’s This Has to Be Funny (recently named Record of the Year by Laughspin.com), but it was never a let-down or a retread to hear them again. In fact, it was even more interesting to see these routines onstage. On the podcast they were stories, but in seeing and hearing them told again to a sold-out audience, you couldn’t help but notice how they had progressed into becoming fully-formed pieces of his routine. I think that we’d all come to this show because we were comedy nerds, and because we loved the craft and the craftsman. Seeing Maron trim the fat off of the stories that I’d already heard (and that nearly all of us had already heard) about his near-death experience on an airplane or about masturbating in his hotel room was fascinating because I knew that he would do those same routines at every show – maybe up to 6 times in a weekend – and that each time it would sound the same and each time it would feel the same to everyone in the audience. And, by saying it would feel the same, I mean that it would sound like the story was that spontaneous every time, and that it was new and exciting. When Maron joked about how he thought that he honestly might die when his plane hit that turbulent patch and about how his moments in his life flashed before his eyes, he spoke in a way that had all of the energy of something that only happened yesterday, instead of months ago. It’s all so natural and yet, we all knew that it was practiced and refined. It was all incredible to watch, because it showed me his growth as an artist and a performer. Maron suddenly seemed like more than just a comedian, he was a bonafide storyteller and monologist. Even in the space of one year, from the time I’d seen him perform at that suburban club last February, I could see how much better he was, even at just talking. He was comfortable and engaging in a way that he hadn’t been before. He wasn’t a man trying to win anyone over or take control; he was a man holding court over a group of friends and acquaintances.

Throughout his set, Marc worked through a bunch of his new material. He’d occasionally pull out a scratchpad that he’d penciled-up backstage and talked through what new bits he liked. He tried out something about how he was trying to work out a bit about heel inserts. He continued this way, talking through thoughts that he’d had and notes he’d scribbled on a napkin. He talked about how ridiculous it was that he’d decided to vacation in Seattle in November. He hit upon some standard Seattle tropes like coffee and rain. He affectionately called us “wine-drunk Earth-nerds” and lampooned our aversion to umbrellas. The comedian talked about his Thanksgiving dinner at a vegetarian restaurant (“Nothing is more exclusionary than large groups of people having a good time”) and his trip to the EMP rock and roll/science fiction museum (where all he could think was, “What is this place? A room of Kurt Cobain, a room of Jimi Hendrix, and then whatever the hell else we could think of? A room about Avatar? Sure! Why not?”). He launched into something he calls his “honest mic check,” a routine where he alternates, “Check…check..one…two” with lines like, “I disappointed my parents” and “Bad career choice, dreams fading.”

Somewhere around halfway through the evening, Maron began to do some of his older stand-up material. He even introduced these old bits by saying, “I like to do some of my older material at these shows, because a lot of people just know me from What the Fuck.” This was honestly some of my favorite material from the set, and not because it was necessarily better or more touching, but because they were all moments when I could truly see Maron act and perform. They were more practiced and a little more conventional than the material that had popped up earlier in his set. He’d been doing some of them for years but, instead of being stale, they were infused with an enthusiasm that came from his excitement about recreating his former self. His stories about his drug addiction turning into ice cream addiction, or about being put in the outfield during Little League weren’t just routines tailor-made for theater-sized crowds, or routines that were hilarious regardless of how funny you found Marc Maron (or if you found him funny at all). They were routines that harkened back to the angry, pacing Marc of yesteryear, rather than the -as he put it- more contemplative and sedentary Marc that we knew today. Seeing him exaggerate and pace the stage like his younger self and watching him gesticulate and raise his voice gave me an entirely new appreciation for him as an artist and I respected it, both as a performance, in and of itself, and because it showed me a sense of Maron’s own self-reflection and the growing sense that he had about his own legacy and individual place in comedy.

He brought up Jessica again and discussed the details about when and how they first met (again referencing, with a smile, how he was sure that we all knew the story already). He explained how she was a fan who hooked up with him at a Portland comedy festival and, not long thereafter, moved from San Francisco to Los Angeles (but, “Don’t worry,” she said, “I’m not a stalker”). From there, he detailed their tumultuous courtship, how his Blackberry would get alternate picture messages from Jessica (of her vagina) and then from his carpenter (of a custom-made bookcase). “And I gotta be honest, I was a little more excited about the bookcase. I’m not afraid to put things in that.” Maron closed out the bit by talking about a particularly gnarly screaming match that they’d had, in which a frightened neighbor had come to the door and pleaded with them to stop arguing. It was that night when they first said “I love you.”

But in spite of everything that I’ve written here, in spite of the times that I used the words “rage” or “anger,” I really want to emphasize that Marc Maron never got truly dark or truly angry. The descriptors of those emotions came through as parts of his stories and as major themes of his act, but real and true misery never once came through in his attitude or mannerisms. Throughout the evening there was never anything but a feeling of warmth and togetherness, both in the crowd and onstage. It seemed like even when what I was hearing were stories about shouting at girlfriends, having no one to turn to, or being forty-four years old and still jerking off in the living room, the way in which I heard them was one in which there was still hope and where things would always get better. Marc Maron’s tone suggested that while it’s true that we can all become angry and insecure, life really isn’t much more than a comedy of errors and maybe if we take a chance and lay everything on everyone all the time we might just get some love back. Maybe we’ll find ourselves with the love and respect that we always wanted. It’s worked for him and it’s what we experienced there that night. Marc Maron is just like every one of us that was there in the audience, even when there are times that we don’t want to admit it to ourselves. We’re all prone to frustration, anger, and insecurity, and seeing Maron transform those feelings into something and to come out the other side was both refreshing and inspiring. I didn’t come to see him for an escape, I came because I wanted to learn something about myself and I wanted to grow as a man and as a human being. I came because I wanted to laugh at the joy that I’m connected to someone else and, on that night, connected to everyone else. As much as we know that each of our internal monologues are idiosyncratic and unique, there’s a whole lot of people out there who are just like us and, on that night, I felt like we were all together and that we needn’t worry because, as long as we keep at it, we just might get it all under control.