Sufjan Stevens Films Something Concrete : “The BQE” Reviewed

Multi-instrumentalist and songwriter, Sufjan Stevens earned his most notable success through 2005‘s Illinois album. The 22-song ode to the Prairie State launched both Stevens and his “50 States Project” into the public eye. In 2006, he followed it up with The Avalanche: Outtakes and Extras from the Illinois Album and a 5-disc box set of Christmas music but, since then, the releases have pretty much ceased. There’s a strange conflict created in the logic of many of Sufjan‘s fans because, although they want to hear a “new” project from him, they are also focused around what the next installment of the last (50 States) project is gonna be. People would often prefer to buy the same album over and over again than risk having an artist grow in a direction that is uncomfortable for them to deal with. For anyone with logic and reasoning skills, it’s clear that Stevens will never write an album for each of the 50 states, unless technology and/or his work ethic changes drastically. I don’t think that the artist’s intentions or claims are dishonest but, even by churning out an album every year, it would still take him until the age of 82 to finish the project. Music aside, I am acquiring a growing respect for Sufjan‘s approach to the creative process, which involves healthy doses of patience, a virtue that I have trouble possessing. His focus seems to be more about the process than the result and, whether or not you enjoy those results, his dedication and sincerity is undeniably commendable. He seems to be content with investing as much time to create, or even re-structure, a project until it’s just the way he had envisioned. In fact, October 6th marks the release of Run Rabbit Run, a reworking of his 2001 Chinese Zodiac-themed, electronic album Enjoy Your Rabbit; this time, with all string instruments.

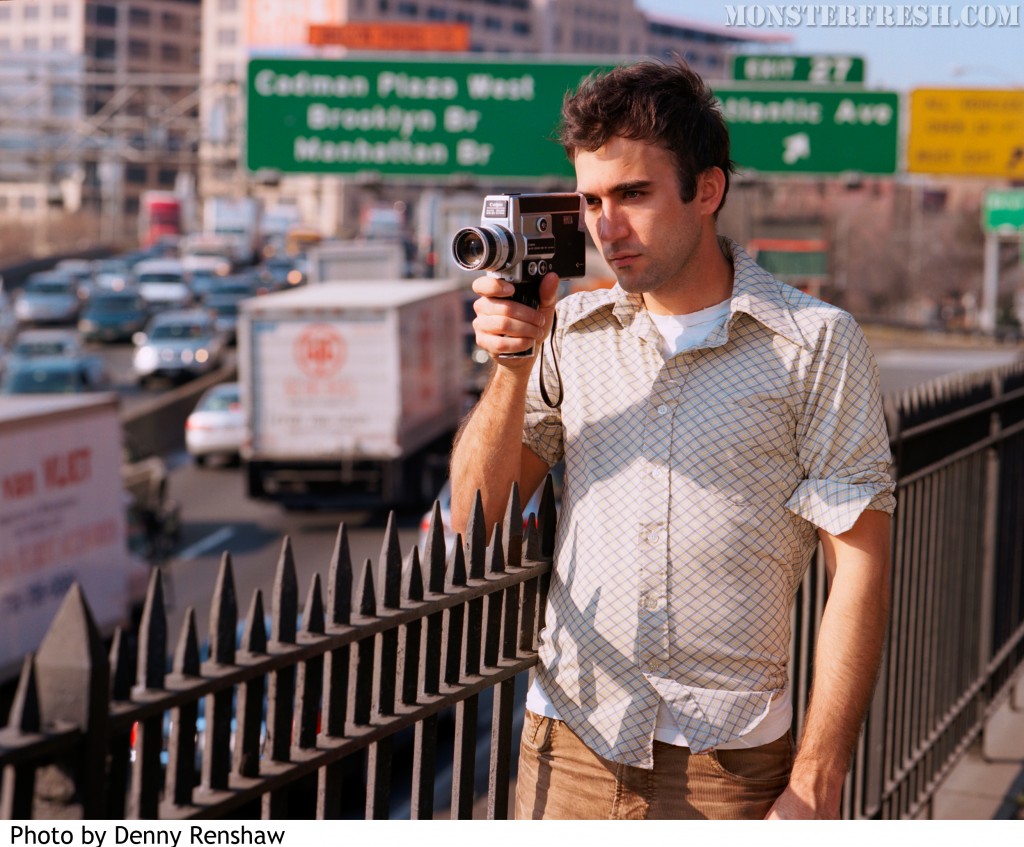

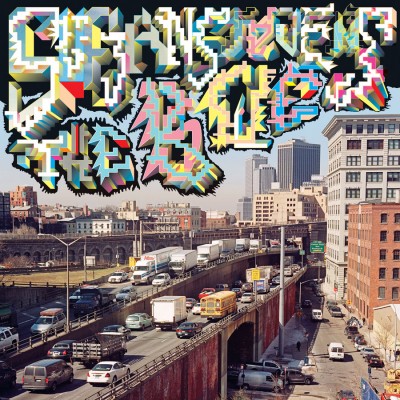

Recently, I had the opportunity to view one of Steven‘s most ambitious projects yet. In usual Sufjan fashion, The BQE is based around a very specific theme; The Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. Like the 50 states Project, it’s geography based, and the music is completely instrumental, like that of Enjoy Your Rabbit. There is one aspect that puts The BQE in stark contrast from any of his previous work, however, and that’s the fact that it’s also a film.

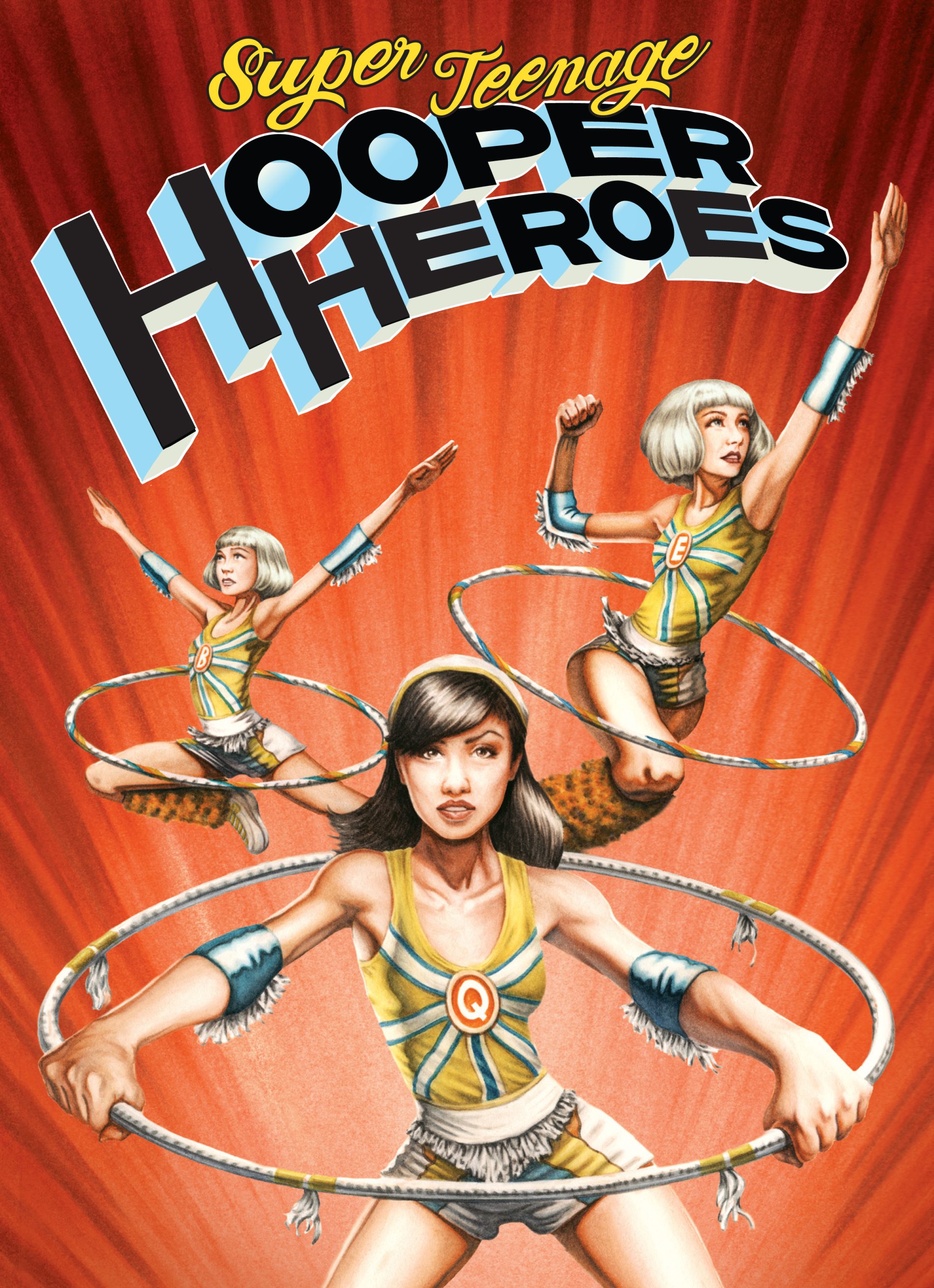

The BQE project was originally commissioned by the Brooklyn Academy of Music and presented in October of 2007, as part of the Next Wave Festival‘s 25th anniversary celebration. Described as “a cinematic suite inspired by the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway and the Hula-Hoop“, the presentation involved a 35-piece band and orchestra, three simultaneous film projections, and live hula hoop crew, during its 3-night run at the Howard Gilman Opera House. A week after the shows, Stevens entered a studio with the orchestra and recorded the soundtrack but, for one reason or another, the project was shelved. After two years, Sufjan finally took on the daunting task of pulling all of the elements together into one somewhat concise form. On October 2oth, The BQE will be released in a deluxe “home version”, which includes the soundtrack as well as a DVD.

The BQE project was originally commissioned by the Brooklyn Academy of Music and presented in October of 2007, as part of the Next Wave Festival‘s 25th anniversary celebration. Described as “a cinematic suite inspired by the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway and the Hula-Hoop“, the presentation involved a 35-piece band and orchestra, three simultaneous film projections, and live hula hoop crew, during its 3-night run at the Howard Gilman Opera House. A week after the shows, Stevens entered a studio with the orchestra and recorded the soundtrack but, for one reason or another, the project was shelved. After two years, Sufjan finally took on the daunting task of pulling all of the elements together into one somewhat concise form. On October 2oth, The BQE will be released in a deluxe “home version”, which includes the soundtrack as well as a DVD.

I found a showing of the film in Seattle, thanks to The NW Film Forum holding a limited engagement. The screening room had maximum occupancy of only 49. There would have just been barely enough room to contain the full cast of performers from the original BAM shows, before risking a violation. Before I attended the showing, I knew very little about the history of the project, but I had already heard parts of the soundtrack. From what I gathered, I assumed that it would involve some instrumental music stacked over a lot of imagery involving asphalt and vehicles. Strictly based on those limited assumptions, I really wasn’t that far off.

[vimeo width=”600″ height=”450″]http://vimeo.com/5682252[/vimeo]

The movie began pretty much like the trailer above, with a shot of the expressway in the distance and the hula hooping trio, only slightly more drawn out. The simultaneous 3 frame structure continues through out the entirety of the the film, as does the format of utilizing a strictly musical audio track to narrate it. Technically, The BQE is little more than 40 minutes of expressway footage coupled with dramatic orchestrations, but it’s not as monotonous as it sounds. It’s the various ways that the imagery and sound are constantly re-presented , which can be credited with giving the film it’s depth and keeping the viewers engaged.

After the introduction sequence and it’s corresponding music (“Prelude on the Esplanade”/”Introductory Fanfare for the Hooper Heroes”), the film transitions into images of old NY architecture, which can be viewed from the expressway itself, and then to the traffic that moves through it. Twinkling piano ripples enter in, as this portion marks the first of 7 movements in the production. Each segment is consciously arranged this way, with an accompanying musical piece. It’s all very symphonic and the unfolding of the musical elements play similar to that of a ballet. Without the footage, this movement (“In the Countenance of Kings”) alone could lend itself to imagery of Snow White or Little Red Riding Hood, gently entering a forest clearing as little woodland creatures slowly expose themselves. The notes dance around, almost romantically, and then plunge into dark dramatic moments of deep passion, before floating back out like a hummingbird. Meanwhile, the, otherwise mundane, imagery flashes across the screen in triplets and is given new life through its altered contexts.

Storage facilities, graffitied-out building walls, and auto auctions with an American flag/giant inflatable gorilla advertisement graced the screen. Once the expectations of what deserves attention and focus have died, some really fascinating concepts begin to pop out organically. The subject of the film is a strip of road that is widely regarded as a congested eyesore and which, for all intents and purposes, was constructed over 25 years in a struggle for functionality. There are many problems that could be focused on with the expressway, including much of the view that it provides, but there is also a lot of craftsmanship involved that is often overlooked. After viewing the various plays on imagery, my thoughts shifted from urban blight to the actual effort and beauty behind the scenery. At one point, a McDonalds restaurant even comes across as majestic, instead of as a corporate threat to American consumers.

The BQE is shot with both Super 8 and 16mm film. Super 8 provides the bleak, washed-out tones and nostalgic imagery, prominent in so many grainy family home videos, not to mention The Wonder Years intro. I’ve always felt that the film produces a somewhat, frantic feeling, as if the images were trying to catch up with real time, so it works incredibly well with scenes involving automobiles and gridlock. The 16mm footage was shot with an old school 1960‘s Bolex camera, utilizing it’s in-camera editing capabilities. Since the scenery of the film is limited to 12.7 miles of concrete and mortar, the transitions are often very subtle, but that actually helps ad to their effectiveness. During, what I later discovered to be, the second movement (“Sleeping Invader”), notes began to mirror the sounds of bells and the happy toot of car horns. The tri-panel display shifted from showing primarily related images to more thought provoking and contrasting subjects. A panel featuring a shot of a land fill would share the screen with scenes of the open water or rows of graveyard headstones would be replaced with rows of empty cars in a parking lot. These are the aspects which save the film from slipping away from the viewer and help manage to keep it interesting, because the viewer is allowed to draw their own conclusions about the what these moments may symbolize.

After all of the elements began to gel, the first interlude (“Dream Sequence in Subi Circumnavigation”) presented itself.

[vimeo width=”600″ height=”450″]http://vimeo.com/6488845?hd=1[/vimeo]

Weather or not “Subi” was an auto leasing reference to “Special Unit of Beneficial Interest“, I don’t know but, by this point, I had already began to view expressway as a living entity and each of the individual vehicles on it as working togehter for a common goal. After the chaos of the swirling hoops and tires of the interlude, the film spill out into the sound of playful stacatto plucks and little zippy cars. This third movement (“Linear Tableau with Intersecting Surprise”) truly embodies it’s title, as little groupings of steel boxes slide across the expressway like products on a factory conveyor belt. Images of apartment windows formed questions for me about where the people were actually traveling to. It seems as though everyone is so urgent to transport themselves from one compartment to another and maintain a separation from each other. The odd thing about this suggestion is that there is the duality that also implies the exact opposite. Generally, when viewing something such as traffic, I notice the separation between objects and not their unity. The same is true with a marathon or in NASCAR, because there is a inherent conditioning to edge someone out and grasp for dominance in those situations. This time, however, I saw the cars more as ants working in unison. Although these are two very contradictory concepts, they work off of each other and suggest more of a multi-angled view and fresh perspective than they present any conflict.

As the vehicles shoot across, up, under, and around the concrete assembly lines, the intensity continues to build and take flight with trumpeting horns and flurries of strings. The action rises until the bottom eventually drops out and transitions into a glitched-out IDM and Drill n Bass sequence of time-lapse video and blurred imagery. This movement (“Traffic Shock”) was my favorite, both visually and soundtrack-wise. This segment was like a shot of adrenaline or a key bump on Space Mountain, with neon streams/blurs of time-lapse traffic and head lights pumping through concrete arteries. Camera angles shifted around with various night shots and the glowing beams of smeared automobiles gave off a heavy Tron-like, futuristic vibe and whipped around the little tracks like Mario Cart. The BQE was really beginning to solidify itself as more of a visual artwork than any sort of story or message based film.

[audio:http://monsterfresh.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/07-Movement-IV-Traffic-Shock.mp3][“Movement IV—Traffic Shock”]

Up until that point, the pacing and usage of the triple-pane method seemed much slower and less overt. At times, each panel would present a different image while, at other times, each one would be a slightly different angle and/or lapse in time of the same shot. The images often seemed as if they’d flow into one another, as if a car was driving through one frame to the next. Sometimes the same image being run at different intervals would create this effect. For example: all 3 panels would show the same shot of the Statue of Liberty with a boat passing in front of it but, by running each one at slightly different times of eachother, the boat would exit the left side of the right frame as the middle frame showed it entering and caused it to look as if it was driving through. It was like the video equivalent of a musical round. The spontaneity and movement of the flipping panels often even felt like a game of 3-Card Monte. These aesthetic approaches didn’t entirely halt after the fourth movement, though. Instead, they were simply mixed in with new ones, while the usage, experimentation, and aggressiveness of effects were being upped, all around. The aftermath of the electronic chaos brought the royalty and fanfare of trumpets, along with symmetrical landscapes and the mirroring of images. By grouping footage next to inverted versions of itself, fascinating compositions were formed that were larger and more powerful than the original frames would have been alone. Frames were aligned in ways that blended them together and formed zig-zagged kaleidoscopic mandalas like casino carpeting. Cars would dance and crisscross through each frame like blood cells in an ant farm. At one point, the images even momentarily took on the shape of an abstract robotic entity for me; an Optimus Prime of medians and overpasses.

As the film continues to wind down, new and old subjects continue to be mixed into the batter. The Hula hoopers return and carnival scenes of Coney Island are introduced, as well as tranquil moments of panoramic skylines.

The most obvious comparison being drawn to The BQE is with Godfrey Reggio‘s groundbreaking 1982 classic, Koyaanisqatsi. In fact, I find it hard to believe that anyone who’s seen both films wouldn’t make note of the similarities instantly. Each of them involve symphonic orchestrations and suburban landscape shots, but Koyaanisqatsi [along with sequels Powaqqatsi (1988) and Naqoyqatsi (2002)] marked a cinematic breakthrough. The BQE, which borrows from the Quatsi format heavily, is hardly as innovative, but I’m not sure that it’s necessarily supposed to be. Reggio‘s film covers a lot more territory with its footage and subject matter. It uses sweeping crane shots to pan down over both rural and urban landscapes, while The BQE relies primarily on more static shots. The cinematography in Reggio‘s classic also incorporates multiple drawn-out, zoom and slow-motion portraiture shots, bringing attention to the people existing in and interacting with the environments being spotlighted. It also features a Phillip Glass soundtrack with memorably haunting chants woven throughout. Besides the “Hooper Heroes”, Sufjan‘s project is much less overt, as far as addressing any direct human involvement. In fact, The BQE is much less overt in most aspects. In reference to his triumph, Reggio has been quoted as saying that, “it is up [to] the viewer to take for himself/herself what it is that [the film] means” and I feel that is where the power of each of these films lie. However, by using imagery as potent as explosions and hospital rooms and by editing drastic cuts from circuit boards to near identical overhead layouts of city-scapes, some connections feel more insinuated in Koyaanisqatsi. Steven‘s main interest with the 1982 film seems to be strictly with zeroing in it’s minimal freeway scenes and expanding upon them.

The BQE is not a re-invention of the wheel, by any stretch. Some of Sufjan‘s shots are almost identical to those of it’s predecessor but, by maintaining his focus on one solid piece of subject matter, it allows for the fledgling filmmaker to explore it with a multitude of different approaches, angles, and avenues (pun intended). Even as someone who loves Koyaanisqatsi, I was still able to really enjoy The BQE and gain something new from it. Sufjan Stevens has admitted to having an “obsession” with the American landscape and has said that his 50 states Project relates to his fascination with “understanding the american identity“. I think that I enjoyed The BQE, which easily could have come across as contrived, because I could sense an honest intention in the film.

I think that it’s a mistake to approach this film with any expectations. If you go in with the hopes of seeing a historical documentation of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, a standard Sufjan Stevens piece, or even a new Quatsi installment, you’re risking disappointment. I also believe thta, if there’s any message at all to the film, it also stems from that concept of avoiding expectation. As the film settles in, and the viewer is forced to accept and embrace where the expressway will or will not take them, it becomes clear that the expressway is as much of a destination as it is a structure of transport. Honestly, the most impressive thing about the film is the way that it’s all painstakingly edited together in a magnificent and elaborate cohesion. Like any good piece of art, The BQE should be viewed more emotionally than intellectually. If you’re able to go in with an your eyes, ears, and mind “open” and appreciate it for it’s sensory contributions, I think that you may find it to be a solid offering. If you want to see Sufjan in a romantic comedy, because you think that he’s dreamy, or if you hate art films, this probably isn’t going to work out for you.

The Official Release / Live Performance

For the official release of The BQE, Sufjan Stevens and Asthmatic kitty have thrown together a couple of unorthodox packaging options. Along with the film and soundtrack, Stevens has also teamed up with, friend and illustrator, Stephen Halker to create a 40-page comic book (pictured) and a View-Master reel. Each of the 7 images on the reel is meant to represent one of the 7 movements from the film/soundtrack. The comic heroicizes the Hooper Heroes and further explains the symbolism through the following storyline:

For the official release of The BQE, Sufjan Stevens and Asthmatic kitty have thrown together a couple of unorthodox packaging options. Along with the film and soundtrack, Stevens has also teamed up with, friend and illustrator, Stephen Halker to create a 40-page comic book (pictured) and a View-Master reel. Each of the 7 images on the reel is meant to represent one of the 7 movements from the film/soundtrack. The comic heroicizes the Hooper Heroes and further explains the symbolism through the following storyline:

“three extra-terrestrial superhero sisters (Botanica, Quantus, and Electress) use hula-hoops to combat the “the Messiah of Civic Projects,” Captain Moses, and his totalitarian social architecture.”

Here are the full details of the packaging options, as well as information regarding an upcoming live performance :

The double-disc album will include the original film on DVD, the original soundtrack on CD, a 40-page booklet (with photos and liner notes), and a stereoscopic image reel (aka View-Master®), created by illustrator Stephen Halker.

The limited edition vinyl is available as a double gatefold and includes the soundtrack on 180-gram vinyl, a large-scale 32-page booklet with liner notes and photographs, and a 40-page Hooper Heroes comic book.

And on October 24, 92YTribeca will host a release party for The BQE. This will include a showing of the film as well as a performance from string quartet Osso (playing selections from Run Rabbit Run), the recently-announced re-imagining of Sufjan’s Enjoy Your Rabbit. Roberto C. Lange (aka Helado Negro) will DJ.

{Tickets are only $12. CLICK HERE to check for availability.}