Appetite For Destruction – Robert Williams and the Birth of Lowbrow

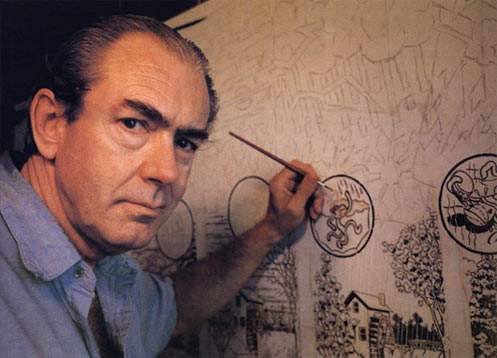

credited with coining the term “lowbrow” and even with being the father of the entire art movement, it’s time that we give a little coverage to Robert Williams

A decent percentage of the art that we’ve featured on the site could fall into the category known as “Lowbrow.” Like similar semi-derogatory catch-all terms (see Krautrock), many of the artists associated with that label reject it and resent its usage, while others; like recent interviewee, Dave MacDowell, don’t really seem too concerned with how other people choose to refer to their work, one way or another. Drawing from such influences as underground comix, hot rod Kustom Kulture, tiki culture, carnival freak art/banners, pulp magazine covers, Mad Magazine, tattoos, and B movies, lowbrow has come to represent a mixed bag of, generally sub-culture-based, visual artwork that was never considered valid or respectable enough to be showcased in fine art galleries and higher end establishments. As the movement has grown, there are some common threads between artists, but there is also some debate about what exactly “lowbrow” encompasses and where/if the line between psychedelic, illusionistic, pop-surrealist paintings and the rest of the work exists. And the movement has grown, with more and more galleries becoming available to showcase the work, along with the pool of artists who create it. Whether this growth is necessarily a positive is something else that’s also been brought into question in recent years, quite notably by the very man who is credited with coining the term “lowbrow” in the first place–a man who has also come to dismiss the term himself–master painter, Robert “Robt.” Williams.

When most people hear the phrase “Appetite for Destruction” they immediately think of the 1987 debut LP for Guns N Roses. It’s likely that they’ll even think about Billy White Jr‘s now-iconic image of the Celtic cross mounted with figures of all 5 band members in skull form, which was originally designed as a tattoo for Axl Rose and ultimately became the replacement album cover art. Some folks might even remember the original banned artwork for the release, which featured the image of a futuristic robot in a trench-coat sexually assaulting a girl, as some sort of vicious, dagger-toothed, blood-red, chrome plated, mechanical, demon came spinning over a wooden fence to destroy it. Even less people will recognize that GNR‘s album actually took its name from that very painting, which was created by Robert Williams a full 9 years prior, in 1978.

!["Appetite for Destruction" [click to enlarge]](http://monsterfresh.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/robt-williams-app-destruct.jpg)

[click to enlarge]

Raised around a car hop-staffed drive-in restaurant that was owned by his father, who also owned a stable of stock cars, Williams was drawn to hot rod culture at an early age and, in 1965, he was hired to work on graphics and advertising for Ed “Big Daddy” Roth, while in his early-twenties. A legend in his own right, Roth was a major contributor to Kustom Kulture and it’s aesthetic. Aside from his highly impressive output of custom vehicles; which contained some extremely forward thinking, and innovative body styles with immaculate pin-striping, paint work, and design–some cars even possessed tripped-out, transparent sci-fi space domes; “Big Daddy” was also a pioneer and the catalyst for a wide-spread craze with his airbrushed “Weirdo” T-Shirts that featured his monstrously gruesome trademark characters like the bug-eyed, jagged-toothed Rat Fink, tearing around in hot rods. A painter since the age of 15, Robert now had the opportunity to help influence the culture that had been influencing him, directly. His impressive ability to master such skills as emulating the effects of chrome unlike anyone else, was not only a reflection of his own inspirations, it was also a reflection of his determination to continuously work toward mastering/understanding his craft and of how his skill set would consistently continue to improve to this day, through sheer passion and invested energy. He possesses both the need and adaptability to tackle difficult and interesting new elements, and present them in new refreshing ways, as evidenced by his penchant for compartmentalizing sections of his work to represent such concepts as dreams, contemplation, lapses in time, and alternate dimensions within them.

!["The Girl with the Faberge Ass" [click to enlarge]](http://monsterfresh.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/devil-bootie.jpg)

[click to enlarge]

Controversial, French Dadaist, Marcel Duchamp spat in the face of the art world and it’s standards back in 1919 with his “ready-made“, titled L.H.O.O.Q, which involved him scrawling a goatee onto a postcard of The Mona Lisa. Warhol was somehow infiltrating the straight world with his own satirical take on art and culture in the Sixties, but Williams and his crew just weren’t going to get the same welcoming. Perhaps Warhol‘s acceptance actually stemmed from his questionable skill set, rather than in spite of it, and that was the major difference that separated him from the meticulously detailed illustrative style of the underground comix crowd, since their time periods did coincide. As for Duchamp, L.H.O.O.Q was an implied vandalism and rejection of an incredibly famous and realistically rendered image. Through the Sixties and up through the 80s, there was a growing affinity for conceptualist, performance, and minimalist art, coupled with somewhat of a disdain for highly skilled realism, which was considered elitist and bourgeoisie. But, like Tom Robbins asks in his novel Still Life With Woodpecker, “who will control those who control those who control” (I think that’s the quote?), referring to the idea that, once the oppressed overthrow the oppressors, they, in turn, often inherit that role as oppressors themselves.

The conceptual art movement finds its highly subversive origins credited to Duchamp as well, and, more specifically, with the artist’s 1917 sculpture of a urinal titled “Fountain.” But, regardless of it’s roots as an artform founded on the promotion of ideas and energy over aesthetics and the final manifested products that they yielded, conceptualism and minimalism had gained a dominance and, the aesthetics are what forced Williams, Crumb, Wilson, and the rest to remain slightly off of the grid. Their understanding of their craft and the level of skill and the detailed precision at which they pursued it was an unfortunate, and somewhat unjustified, strike against them. They were now the subversives and the fact that their content was so appallingly… well, subversive, is what compelled the, arguably, misguided art world to ignore them. For whatever reason, the powers that be must have believed that holding onto a formula that was becoming structurally outdated and restrictive, in it’s own right, would still make them cutting edge, revolutionary, and groundbreaking. In reality, minimalism, and especially conceptualism, have demonstrated a potential to birth some of the most pretentious results in the history of art, and to elevate the ideas of what does and does not constitute “art” even higher up and away from the common people more than ever. They were supposed to be representing the work of the soul, when the soul had become increasingly absent, but now the passion that Wilson and his cohorts were bringing was being ignored for stylistic reasons. It’s hard to deny the serious passion of someone whose schedule long consisted of waking up at around 4:15 am and painting day-after-day-after-day away, on end, but that reality didn’t seem to be getting Robert anywhere; at least not into any fine art establishments.

!["Malicious Resplendence" [click to enlarge]](http://monsterfresh.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/Malicious_Resplendence.jpg)

[click to enlarge]

This fight for a voice for himself and for his contemporaries has carried Wilson into the present day, through the ambitious launching of Juxtapoz magazine in 1994 and to his current foray into casting his trademark, over-the-top visions into massive 3-dimensional sculptures, and partaking in the occasional public speaking engagement. No one individual more than “Robt.” Williams can be credited with giving the “lowbrow” movement a place in contemporary art, even if he himself would rather replace that term with “Conceptual Realism” or, any number of other possible descriptors. Still, Williams has been open about his concerns that, with a greater and broader acceptance, even this formerly-rebellious art form that he pioneered has fallen victim to some of the same downfalls as those that came before it. In the 2005 book Weirdo Deluxe: The Wild World of Pop Surrealism & Lowbrow Art by Matt Dukes Jordan, Wilson sounds almost resentful when he says, “I caught all the fire and opened up the territory for everyone else. Now a lot of people are in this thing because it’s here, it’s a ride and they couldn’t come up with a ride of their own.” He then follows with, “They’re working this thing until they can jump off of it. Maybe I am too. I think this thing will get more and more diluted. People will follow success.” But as he continues, it’s clear that, while he has mixed feelings on the current state of the world that he helped birth, his concerns aren’t with gaining any individual recognition or praise–he gets plenty of that, already–but rather with maintaining credibility in the work at large. His mentioning of the obstacles that he’s battled through–angry feminists, cultural acceptance, etc– are there to highlight that there was clearly a strong belief behind his mission to pave a path for everyone else to be able to reap the benefits from, even in the face of such opposition, but what many of the artists are doing with that freedom has become a disappointment for him. It also raises the question about the importance of resistance and struggle in relation to the vitality, or lack thereof, in the art and the process in which it’s created.

!["The Brain Trap" [click to enlarge]](http://monsterfresh.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/the-brain-trap.jpg)

[click to enlarge]

With all of that being said, Williams is still hopeful–or at least he was back in 2005. “…there are still very intelligent people doing intelligent work because the area that we’re in is so fertile and rich. I think that more intelligent things are coming out of our movement than any other art movement.” And that’s probably true, because, if part of the loose lowbrow framework is defined by the rejected and the underground, the pool to draw from will never be depleted. Even if “lowbrow” continues to become the “alternative music” of the art world, there will always be an underground somewhere that’s developing untouched. As for the guys who have been in the game for a long time now, plenty of them are still producing very relevant work. People like Mark Ryden, Todd Schorr, Ron English, and Wilson himself (aka the guys to steal from) have managed to retain their extremely identifiable, trademark styles while continuing to contribute astonishingly consistent work to the pop-surrealist/lowbrow world. The pool isn’t completely depleted yet. As for the slightly younger set, my hope is that the work of such brilliant and inspiring artists as James Jean, Jeremy Geddes, and Jeff Soto has made Williams feel validated in his claims that quality, “intelligent” work is still being produced throughout the movement.

We are not strictly a visual art site, but I will do my part to try and continue to offer another platform for this type of work, even if it’s, admittedly, sporadic. Before writing this article, it hit me that, although we’ve showcased and supported plenty of lowbrow/pop-surrealist/underground contemporary work, in the past, we’ve never really spoken much about Williams. That’s a reality that is both understandable and borderline-unforgivable, for the exact same reason. With such an important, major figure, it’s easy to assume that covering him would only be redundant, but as a site with one of it’s primary principles being to try and avoid pretentiousness by being as informative as possible, never assuming that the reader has a previous history with any of the subject matter, it was a realization and oversight that bothered me. Hopefully, those of you who were familiar with Robert Williams beforehand have found something of worth in this writeup. For those of you who weren’t, perhaps you’ve discovered the work of a brand new artist, or even an entire genre of art, that you feel is now worth exploring. Have fun sifting through it all, but make sure to take the occasional break or risk your mind congealing into a psychedelic jello mold— there’s a lot of it.

loved your article! I am sorry you didn’t mention Snake Handler… and I’d love to tell you the story as I recall it.

Thanks. I’d be interested in hearing it.

pretty simple really, I was dating the bassist when Divine Horsemen recorded the album, and met Mr. Williams while he was doing the cover for Snake Handler. At the release party, he was sweet enough to let me accompany him when he moved his wicked awesome Deuce Coupe so it wouldn’t get towed. That would have been 1987.

Around 89, my fiancé(not the bassist) and I started seeing Williams through our friendship with tattooist Jill Jordan, and attended a gallery show at La Luz. Mr. Williams was kind enough to autograph three of the lithographs done for merchandising for me. He and his wife had rsvp’d to attend our wedding, but had to cancel when he got a show on the East Coast for the same date. Somewhere, I still have the lovely note she sent me apologizing- I love the irony of a formal note of apology after having accepted an invitation being written on tiki themed stationary!

Ah, I forgot to add- the album was titled Snake Handler after a BBQ I held for the only group of monogamous folks on the scene at that time- we all told stories about our families, and I mentioned that one of my grannies liked to say she’d snapped a rattler like a whip, which resulted in it’s head popping off… as expected of a Texan, lol