Mystic Code’s Wild Ride: Brian Blomerth’s Bicycle Day Reviewed

The Brooklyn illustrator offers a 200pg highly informative, yet psychedelic as all get out, retelling of the discovery & first ever intentional ingestion of LSD

Growing up in the “Just Say No!” 80s and funneled through public school anti-drug programs of the following decade, it’s pretty fascinating to watch this evolution of what the straight world is now determining is or is not still on the forbidden list. Aside from what I’ve always viewed as a thinly veiled attempt to spook elementary children into ratting out their parents for their weed stashes, the D.A.R.E. program essentially lumped all drugs into one singular, murky, and convoluted group, without focusing enough on what differentiates them from one another; either by specific effects, or nature of risk. The message seemed to be that, if I took a single drag off of a marijuana cigarette, I’d go full-blown meth tweak, hallucinate paisley gargoyles, grind my teeth into a powder, fold over in the corner like a smack junkie, and, with absolute certainty, be reaching into my mom’s purse and smashing my little sister’s piggy bank as a hopeless addict for life. For the system to now attempt to untangle that mess, draw distinctions, and backpedal on stances pertaining to some of these drugs, is an incredible step forward, but it also requires them to admit — indirectly, or otherwise — that they’ve been pushing a tremendous amount of propaganda for more than a century (the damaging Harrison Narcotics Act was passed in 1914). And within that time frame, there are certain substances besmirched to such a degree that it would be a miracle if any public relations effort of any magnitude could ever reverse the perceptions that have been so heavily ingrained in the minds of the general population. Toward the top of that list of misunderstood and vilified ingestibles is LSD. That’s why it’s so exciting that a new graphic novel by artist, Brian Blomerth, which focuses on the story behind the discovery of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide-25, presents the hallucinogen through such a refreshing lens, while getting so much about the subject right.

Brian Blomerth is a Brooklyn-based illustrator/cartoonist/musician and self-proclaimed “comic stripper” who has had a varied career providing art work for such outlets as The New York Times, Merry Jane, and Vice; creating zines, band posters, and even doing album artwork for musicians like The Growlers, Pictureplane, and Ryley Walker. I first became aware of him through artwork that he supplied for the highly anticipated, yet short-lived, rap trio, Secret Circle (Lil Ugly Mane, WIki, and… another dude we won’t mention), which featured his trademark anthropomorphic canine characters. From that point on, I began following his Instagram account, @pupsintrouble. When we got the press release asking if we’d be interested in doing a write-up about a book from Blomerth that was centered around Albert Hofmann and Bicycle Day, that was a no brainer.

I’m aware that a lot of people may be less than familiar with Bicycle Day, but it’s something that we’ve actually written about on this site, in the past. Since I enjoy quoting myself like a dubbed bootleg that loses its depth and clarity with each new reproduction, here’s an excerpt from another piece that we published last year about an online blotter/fine-art exhibit.

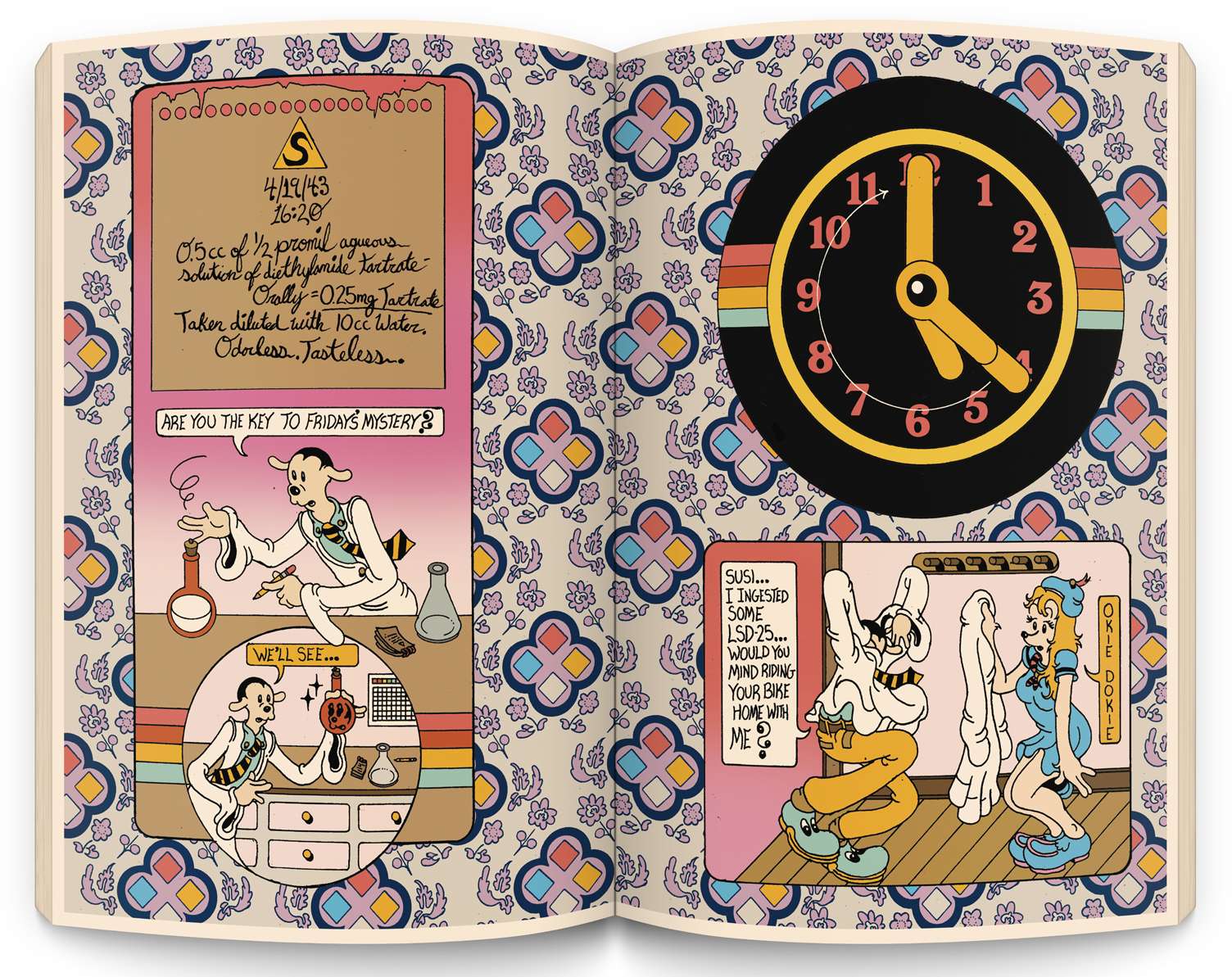

Albert Hofmann (January, 11 1906 – April, 29 2008) is the name of the late Swiss scientist credited as the first one to synthesize lysergic acid diethylamide (aka LSD-25) and documenting it’s hallucinogenic effects on the human body. He did so the old fashion way: by ingesting it. Although he first synthesized LSD on November 16, 1938, it wasn’t until 5 years later — on April 16, 1943 — when the chemist decided to re-synthesize and re-examine his discovery, that he accidentally absorbed some of the substance and experienced it’s effects for the first time ever. Overwhelming as it was, he returned to his normal state after only a couple of hours. Three days later on April 19th, he intentionally ingested 250 micrograms, not realizing that he would only require a small fraction of that, with the threshold actually being a mere 20 micrograms. The story goes that the availability of automobiles were restricted due to WWII, so, with the help of his lab assistant, Hofmann traveled home by bike and began tripping out of his gourd, during the process. It was this experiment that he documented, as the first person to ever truly hallucinate on the drug. That’s where the name “bicycle day” comes from and why it’s a legitimate cause for celebration.

I was really intrigued by Brian‘s idea to create an entire project around the story of Hofmann and his journey. It’s not as if the story has never been documented, because it has, but it’s so often delivered anecdotally and with inconsistencies between sources. The chemist, himself, even wrote in detail of his work with psychedelics in his autobiography LSD: Mein Sorgenkind (LSD: My Problem Child). What Blomerth offers is another way to present the information, using his eye catching graphic style to achieve something more condensed and, in some ways, more direct. That alone was enough to gain my interest, but what drew me in further was the realization that this was much more than a comic of psychedelic trip-out imagery; it was a product of extensive and thorough research. It was a labor of love; it’s very manifestation a mission, of sorts, for its creator. On Bicycle Day of this year, the illustrator expressed as much through the following post on his IG account.

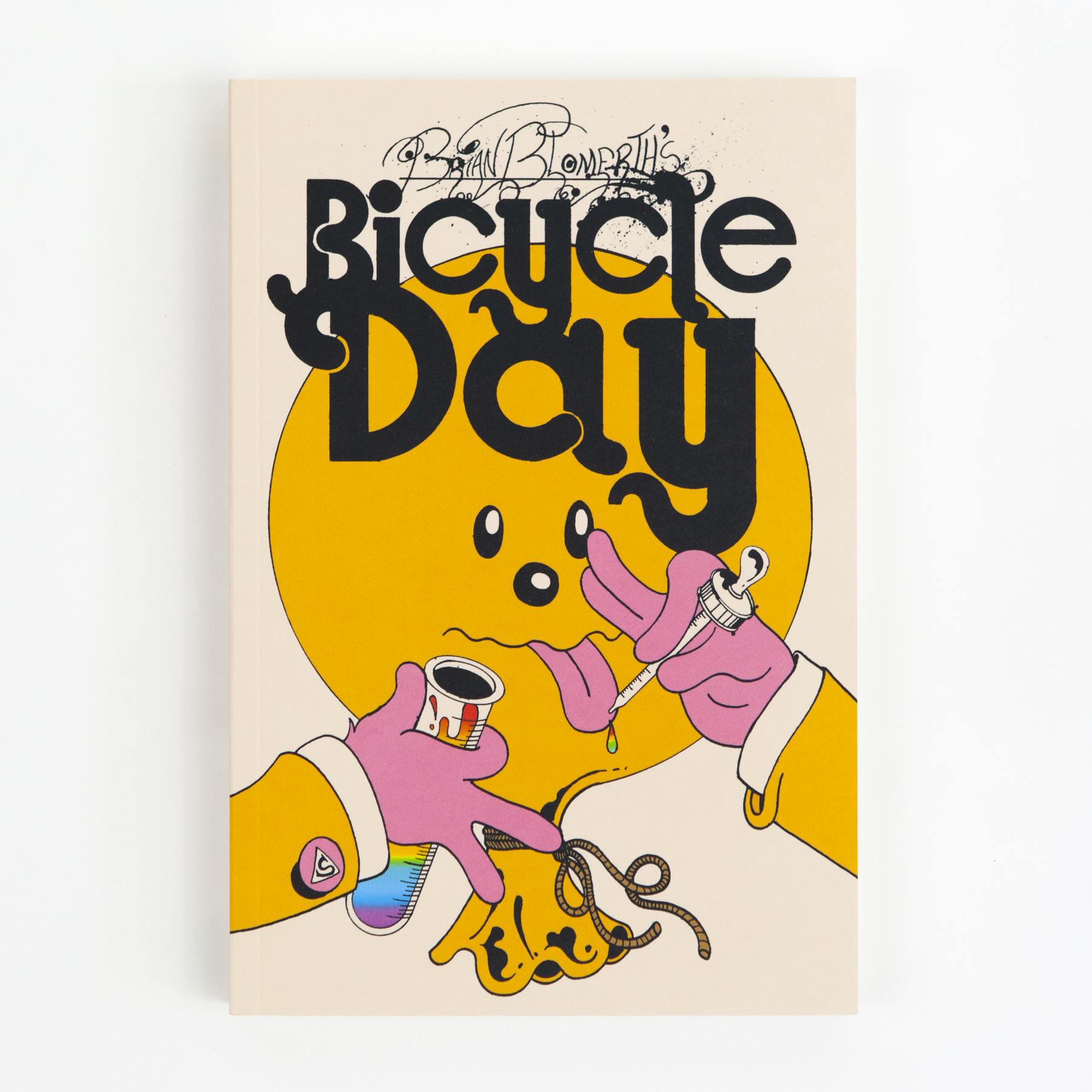

Another thing that felt both promising and inspiring was how Anthology Editions really seemed to be putting their full weight of support, and resources behind Blomerth‘s brainchild. The publishing wing of Mexican Summer‘s reissue imprint, Anthology Recordings, has been on our radar for quite some time, with releases like Tino Razo‘s photography book about skateboarding in abandoned Southern California pools, and Do Angels Need Haircuts?, which chronicles Lou Reed‘s lesser known venture into poetry. From a distance, the publisher appeared to be putting out one high quality project after another, and their latest is no exception. As described in the press release, Bicycle Day is “200 pages of pen on paper illustration with digital coloration, neon Pantones, and spot coloring.” The minute that I got it into my hands, the book felt solid; it has a really nice heft to it. Once I peeled off the shrink, I was pleasantly surprised by the soft, velvety, tactile quality of the cover. I wish I was more versed on the various forms of paperstock to better explain this aspect, but there is an almost rubberized feel to it. While I don’t believe that the content within Bicycle Day suggests something expressly intended for use by those under the influence of hallucinogens, this is, without a doubt, the sort of thing that I could find myself constantly reaching for if I was in that state. I wouldn’t want to put it down, and I doubt that Blomerth was oblivious to that detail when the materials were selected. The pages inside are just as beautiful and engaging, but we’ll get to that momentarily.

Before ever heading into the illustrated retelling of Hofmann‘s discovery, Bicycle Day begins with an introduction by the “renowned ethnopharmacologist and author,” Dennis Mckenna, who “has been a leading thinker on and advocate for the study and responsible use of psychedelics,” since the 1970s. The inclusion of Mckenna provides additional credibility and dimension to the book. For the cover art, Brian Blomerth holds nothing back with very on-the-nose imagery of two hands administering a dropper of psychedelic rainbow liquid to the outstretched tongue of someone with a balloon for a head. Even Blomerth‘s signature on the front is rendered with the same splattered India ink effect that Welsh illustrator, Ralph Steadman, helped popularize through his numerous collaborations with Hunter S Thompson. But, once you sift past the title page(s), a dedication page with a spot to write who “this book belongs to…” on a faux bookplate, and a few illustrations, the introduction quickly establishes this project as something much more serious and analytical, than the outer presentation might otherwise imply.

Mckenna begins his contribution by mentioning the graphic novel for which it is a lead-in, along with referencing Blomerth who created it, but he only does so briefly. From there, he dives head first into his own detailed breakdown of Hofmann‘s story; addressing the “mystic chemist’s” general aims that led him to his discovery, and why what he managed to achieve is so monumental. Meanwhile, he weaves in some greater context to what was occurring, at the time, such as the fact that it was Passover eve, or the horrific aspects regarding Nazi massacres and WWII. Anchored to very scientific data and historical research, the lecturer/author wanders out into more abstract territory to speculate about whether or not there were more cosmic elements at play to even prompt Hofmann to revisit an experiment that he had previously abandoned. He questions how these two worlds — one of optimism, science, and discovery, the other of inhumane terror, great suffering, and destruction — may relate to and reflect off one another. As far as the hallucinogen, itself, is concerned, Dennis‘s position is clear: “LSD is an example of all that is good about humanity: a triumph of science, curiosity, imagination, spirit, and the unending search for meaning and truth.” Dr. Mckenna views LSD as “a gift to humanity from the realm of the perfected archetypes” and the flip-side to Hitler and the holocaust; it is a concentration of righteousness and potential for humanities highest self, while ethno-cleansing, genocide, and eugenics are concentrated evil representing the worst of our capabilities as a species. This is the level of reverence this foreword suggests this subject deserves, and that we can expect if we choose to continue. THIS is the subject that we are dealing with. And even as a simple drug — and simple it is not — there is still duality and layers to it, just as there is to us as humans and individuals. It is both the intensely spiritual, yet cerebral and analytical, Timothy Leary locked in a room meditating end of the spectrum, as well as the body-high Merry Prankster day-glo crazies freaking the establishment. These aspects can inform, rather than work to discount, one another. Mckenna simply sees Bicycle Day as an effective and “whimsical retelling” of a what is still, at its core, a very important subject. And while he goes on to spend the majority of the intro discussing the subject that inspired the graphic novel, rather than the final product, he does break the entire thing down fairly succinctly in his opening paragraph. “The book is a joy to behold: the artwork is stunning and about as psychedelic as it can be without actual pharmacological enhancement.”

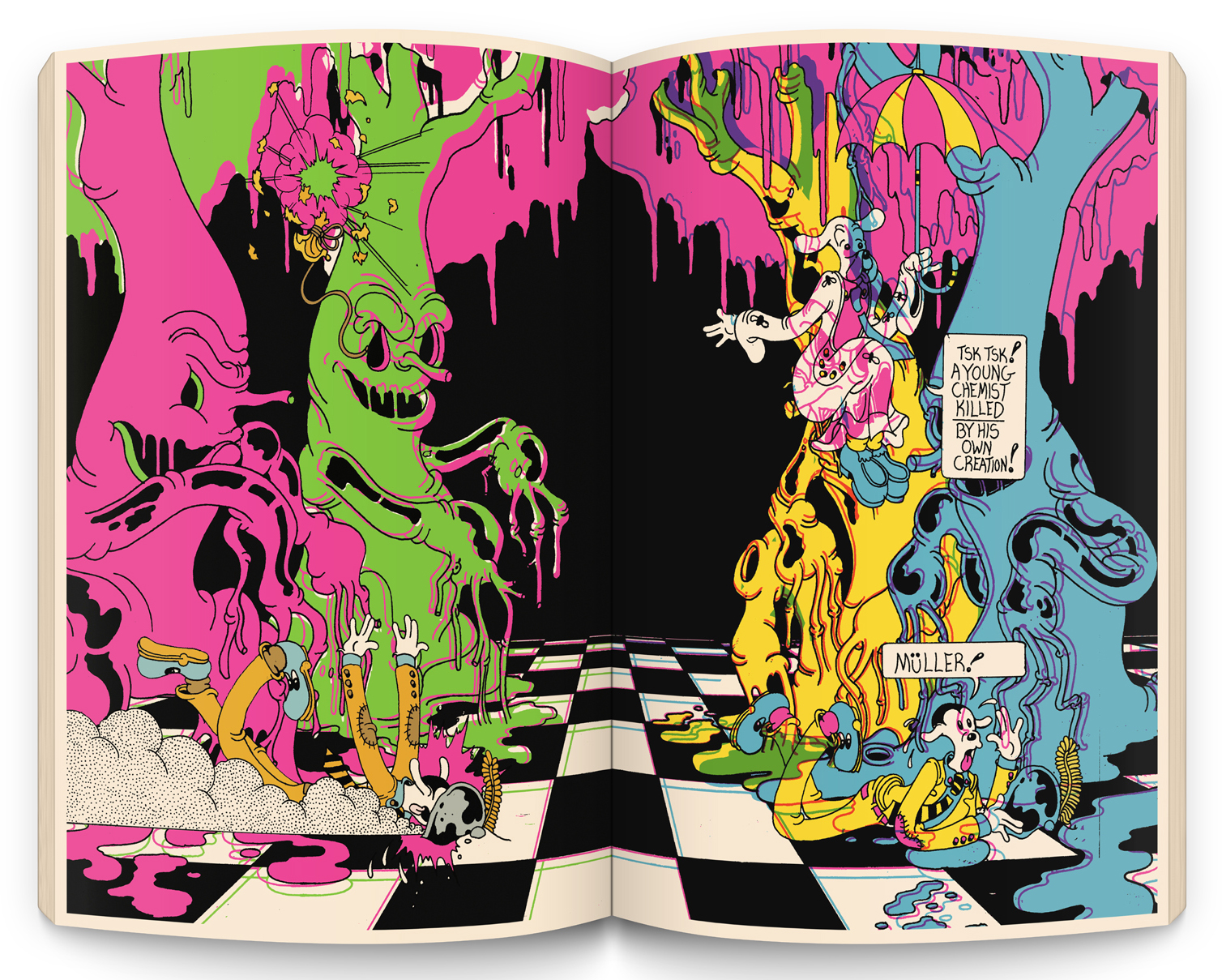

From the first full-page illustration, Bicycle Day is like a technicolor skeet blast to the senses, with vibrant, squirming life packed into each frame like radioactive microscope slides. From the brilliant colors to the awareness of composition, every single page has enough strength to operate independently as a stand-alone work of art. It’s overwhelming in the most successful ways, forcing the reader to decide between stalling out to absorb the full scope and particulars of a given page, and the conflicting urge to race forward to explore whatever might be around the corner. With so much energy and personality, it’s difficult not to feel as if this illustrated adventure deserves to be animated. But while I’d absolutely watch it if that ever happened, the sheer fact that the project already expresses so much movement and breathes as it does, is more so a case for why is doesn’t really need any additional tricks or enhancements.

Keep in mind that this isn’t just a thin pamphlet-style zine, or even the typical multi-panel graphic novel situation; this thing is meaty with textured, blotter-thick paper saturated in ink, and the majority of the panels taking up an entire page, if not two. The drawings work to great effect, allowing you enough space to get lost in the 6 x 9-inch format. With the book being 200 pages and pushing an inch in thickness, it made me wonder if Blomerth would be able to maintain that level of consistency throughout. The fact that he not only follows through on that challenge, but actually manages to turn it up further, is a testament to the amount of time he clearly put into making this thing and, quite bluntly, how much he actually gave a shit to do it.

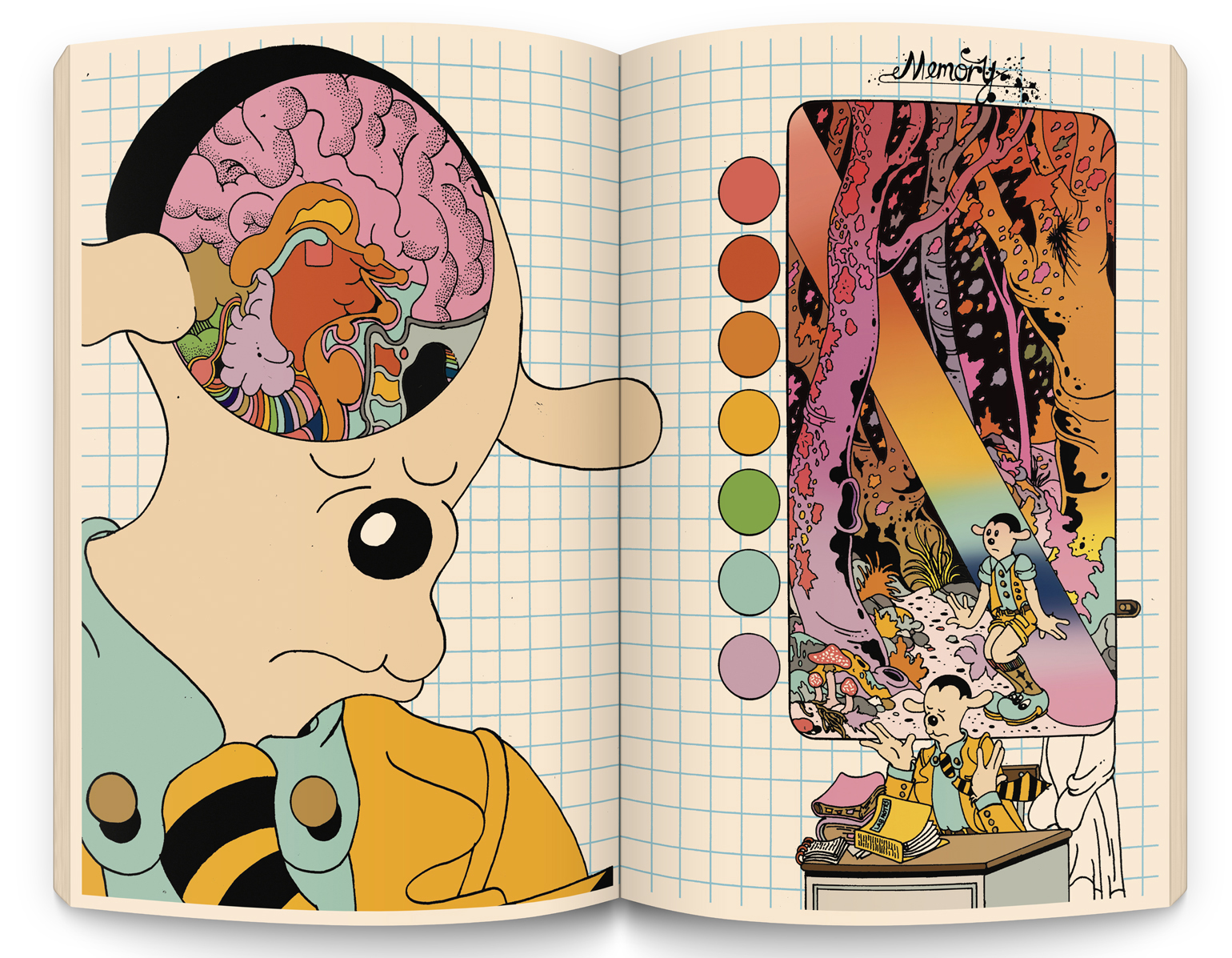

Besides the mesmerizing artwork, the other reason that this story doesn’t fizzle out early on is because of how well Brian‘s genuine affection for the subject matter translates. The dialogue in the book is somewhat sparse, but the attention to detail is remarkable. Not only are dates mentioned at the beginning of particular sections, but with several clocks featured on the walls throughout, one has to suspect that they are set as accurately as possible to the approximate times that specific moments represented were supposed to have taken place. It’s my understanding that the butter/honey toast and milk that Albert snacks on in the book is even true to his diet. There’s also a detailed recipe for a Swiss crepe-style pancake called Cholermüs that his family eats for breakfast, just prior to showing the exact contents of one of his children’s rucksack, as they’re headed to school. Molecular diagrams are featured, as well as very intricate renderings of the equipment used in the chemist’s experiments, alongside precise references to chemicals, temperatures, and procedures. In fact, there is essentially a comprehensive breakdown for how to create the drug, itself, à la Master P‘s “Ghetto Dope” (“make-make-make-make-make crack like this!“). And when I see the insides of Albert‘s home displayed like a diorama, it leads me to believe that the layout was featured that way, because the illustrator was working from a visual impression of that space achieved through the data he’s collected. It’s not always just information for information’s sake, or strictly eye-candy for the sake of aesthetics. Brian Blomerth employs his technical skill in conjunction with meticulous research to construct a world that allows the reader to enter into and experience it as fully as possible.

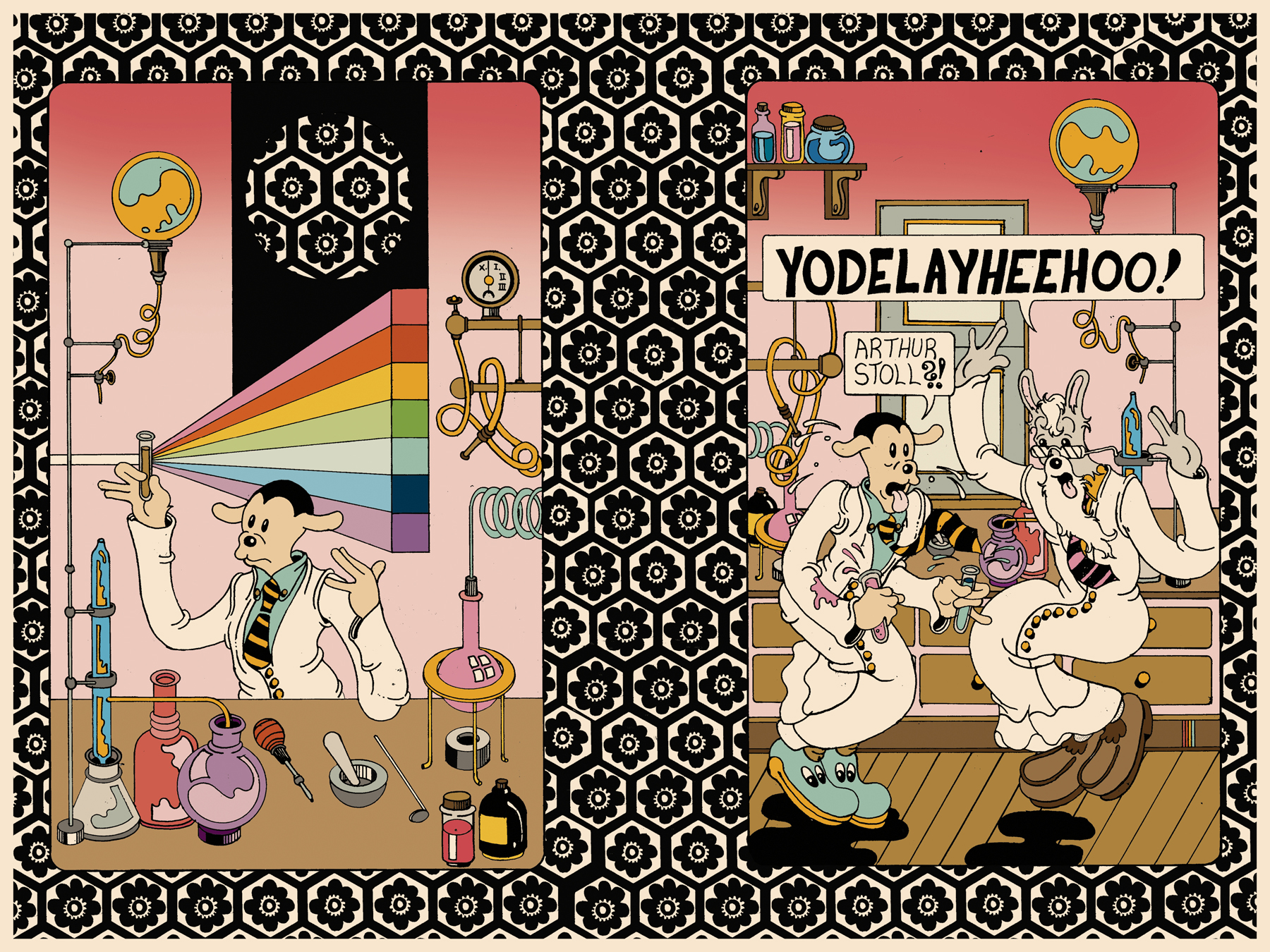

Blomerth‘s Albert Hofmann is an easy character to like: an affable cartoon pup with smiles and eyes on his shoes and a vibe that falls somewhere between a Berenstain Bear and Dagwood from Blondie. While it’s easy to feel as if you’re traveling along with the good scientist as he cruises through the open air of the Swiss countryside, we are equally welcomed into his lab and, with that, into the intensity and focus that he applies to breaking through the obstacles in front of him. One simple technique that I particularly enjoyed was the use of color to set the mood and energy, such as the reddish hues in the lab as he calculates his formulas, or the way that the beautiful gradient colors of the skyline shift to indicate the time of day, whether it’s a gradual fade to dusk or page after page showing the natural progression of a sunrise.

Stylistically, Blomerth seems to pull from a number of different influences. There is an underground comix energy at play, while some of the busier images gave me flashes of Dr Seuss circa And To Think That I Saw It On Mulberry Street or the work of Richard Scarry. Some of the bold colors, elements of the background, and psychedelic flourishes even have tinges reminiscent of a Milton Glaser or Heinz Edelmann. Although less of a direct comparison, I wouldn’t be surprised to discover that Blomerth was a fan of artists like René Laloux (La Planète Sauvage) or, perhaps, Terry Gilliam (Monty Python’s Flying Circus). My mention of these forefathers is merely an attempt to provide some form of reference for Brian‘s own unique aesthetic. I’ve seen people get credit as they shamelessly rip off other artists and, if I wasn’t so adverse to providing those actors with even a modicum of shine, I could call some of them out right here. That isn’t what this is. These references are relevant due to a similar feel and emotional quality, more than anything. There is an abstract familiarity that makes it instantly comfortable, yet a style original enough that it still feels fresh and exciting. Brian Blomerth‘s work looks like Brian Blomerth, and it’s forever identifiable from the very first time that you encounter it.

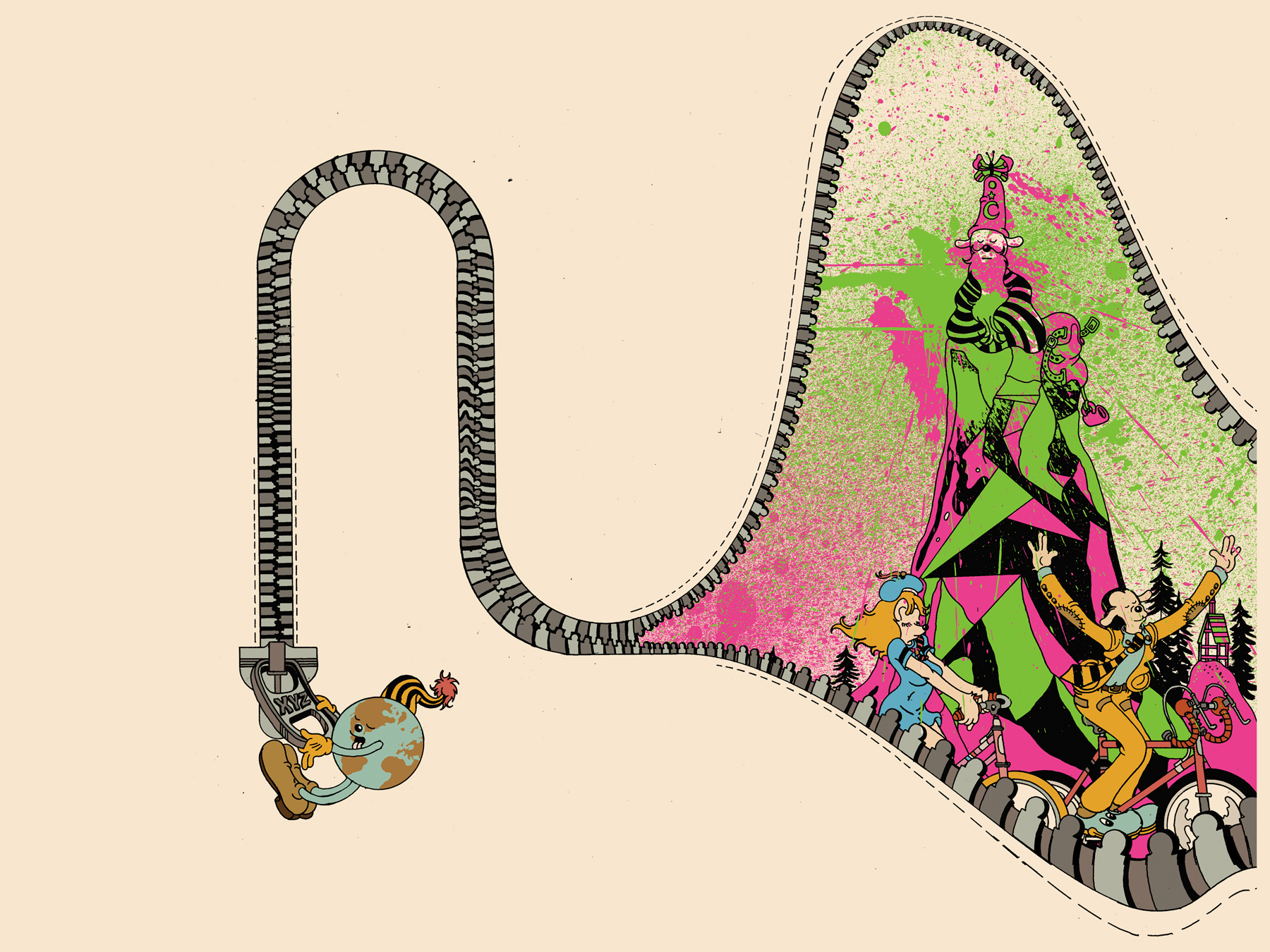

With so much space to deliver a relatively simple story, I feel like the pacing was handled rather well, but the imagery is already so visceral from the beginning that I did wonder where it could possibly go from there. I mean… we’re literally dealing with an environment that, in its most basic state, involves things like rainbow accordions being played by human/dog hybrids sporting various interpretations of lederhosen. It’s how colorful and bizarre everything is that supports the feeling that you’re in another world, but that also has the potential to weaken the effectiveness of later sections where Hofmann is supposed to be moving into an alternate headspace. For example, when he intentionally ingests the 250mg and departs on his 8 kilometer ride home from the office accompanied by his assistant, Susi, there is already an impressive display of animals — several of them hatted (a snake, turtle, porcupine, beaver, raccoon), as well as a goose in a bonnet and a dress-clad swine, etc. — all balancing on top of one another. This is well before the acid even begins to kicks in for him. Fortunately, while Blomerth‘s typical style is left-field and attention grabbing to begin with, his visual interpretation of psychedelia is straight-up fucking bonkers. We get a little taste of that, earlier, when Albert is accidentally dosed for the first time, before it all ends so abruptly. In that moment, we basically experience the process along with our protagonist. When things truly go off the rails, later on, we are given the same experience, only tenfold.

And that’s one of my favorite moments in the book, when the whole thing comes unzipped and he’s fully immersed in the experience. Among the abstract neon chaos, there is a massive faucet that could have been pulled straight from the pinball number count on Sesame Street, and it’s pouring down full force onto the chemist — the normal dripping state that the human mind typically operates in has now had the tap cranked wide open. It’s at this point that Albert states “now this I recognize.” This may be a call back to the recent event of him being accidentally dosed, or, quite possibly, a reference to a childhood memory and “deeply euphoric moments” that he experienced in his youth, which convinced him “of the existence of a miraculous, powerful, unfathomable reality that was hidden from everyday sight.” Highlighted in his own book, and given a brief nod here, it’s part of what drove the doctor to pursue chemistry in the first place. From there come the parts that he doesn’t recognize, and the increasing disorder and pandemonium. The scientist thinks of his family, his mortality, and his life’s work. The printing gets crazier and crazier, the imagery more abstract. It builds, with each page ramping things up further. It’s intended to disorient the senses and simulate the experience through visual art, and it’s not unsuccessful in that respect. Albert directed his focus toward science, after recognizing that he didn’t possess the artistic ability to relate his experiences and visions through such mediums. This, above all else, is where Blomerth succeeds.

After the whole ordeal, which involves a medical doctor being called in and his wife, Anita, frantically racing home on a train from out of town, Hoffman simply chills out and goes to sleep. He wakes up the next morning, on 4/20. Not mentioned is the fact that it was also Hitler‘s birthday, so a bunch of horrific propaganda was being spread to celebrate that in various other locations in the world. For our tale and the revelations therein, none of that matters.

The last few pages that close out this book might be the most important of all to me, because I don’t recall seeing the post LSD experience represented too often, let alone, so wonderfully. The way that this portion is rendered in bleeding watercolors feels like the perfect approach to simulate that rejuvenation. “I awoke… A sensation of well-being and renewed life flowed through me.” “Breakfast tasted delicious.” “Everything glistened in the soft fresh light.” “The world was as if newly created.” This is the experience of stepping out through the other end of that tunnel. After you’ve worked through whatever you have to and flushed out the bullshit, it’s the next day that you get to be at peace. And that’s where the graphic portion of this book ends, the next morning where Albert is overflowing with that tangible appreciation for his life and family.

That’s the whole story. A Swiss chemist synthesizes LSD, shelves it, comes back 5 years later, and has a psychedelic meltdown on two wheels. The book is titled Bicycle Day and that’s what it’s about. Blomerth doesn’t follow the story beyond that incident to how it was perverted, whether through CIA-funded MK-Ultra mind control experiments, warehouse raves, or even 1960s be-ins. To focus so narrowly on this singular event as it does, while employing limited dialogue, it would have been incredibly easy to produce something that began and ended as nothing more than Go Dog Go on acid; and, to be honest, that probably would have sold just as well. What we get instead is a story that provides a feel for Hofmann as an individual, his passion, and what he was trying to accomplish. It gives credit to a man who saw value in his creation enough that he was willing to use himself as a test subject in an effort to create something that has the potential to alter the entire fabric of our universe. LSD-25 wasn’t a total accident, it was very intentional; the results were simply unknown. But, if you think about it, the sheer fact that he feared it might be killing him the first time around, yet followed it up by ingesting it again intentionally, is mindblowing on its own. Sure, many of us may have had similar psychedelic experiences where we question if we are dying and/or transitioning into the afterlife, but never could ingesting a substance like that present greater odds of actually taking your ass out for good, than if you are the very first person in history to ever test it out. The man was definitely committed and bold in his actions.

At the very end, Brian Blomerth provides a series of disclaimers and expressions of appreciation. The first thing that he makes sure to get out of the way is the warning that, “Failure to use a nitrogen atmosphere during distillation of anhydrous hydrazine will likely cause an explosion.” He addresses select areas where he took artistic license, and a spot where he left something off one of the diagrams. He also does his part to deter anyone from using Bicycle Day for anything beyond entertainment purposes, by adding, “if you are using this experimental children’s book as a chemical resource… DON’T.” Among his thank yous, he includes Travis Miller (Lil Ugly Mane), and he also suggests donating to two separate organizations promoting the scientific research of hallucinogens. This sentiment is right in line with the beliefs of Albert Hofmann, who supported and promoted such research until his death from a heart attack at the age of 102. His passing followed that of his love, Anita (94), by only a mere 5 months.

While the Swiss chemist is responsible for numerous other incredible achievements in his field, he seems destined to be reduced, quite simply, to the man who “invented acid.” Even so, that legacy is not something to be dismissive of, or anything that Hofmann ever viewed as any sort of mistake. In fact, he continued to study other plants with psychedelic properties, including peyote and salvia divinorum, with varying levels of success. In 1957, he accomplished the feat of becoming the first person to isolate psilocybin and psilocin from mushrooms. Sandoz Ltd, for which he worked, later sold it under the brand name of Indocybe, while marketing it for use in psychotherapy. In fact, LSD was treated as a promising discovery with numerous applications, for years before earning the negative connotations that are so often applied to it these days. We’ve all heard of questionable government experiments involving LSD, but there have been endless other scientific studies investigating its potential benefits related to everything from easing mood disorders to the alleviation of cluster headaches. It has even been credited for its role in the discovery of the serotonin neurotransmitter system and the first connections between brain chemistry and its effects on human behavior being drawn.

Hofmann initially published LSD: Mein Sorgenkind in 1979. By then, it had been 36 years since he first ingested his “problem” molecule and, within that time, he had watched a groundbreaking new scientific discovery with all the potential in the world, become widely abused in the counter culture and demonized by the government. As suddenly as it took off, it was shut down, and any hope of continued scientific research along with it. The doors of perception had been firmly padlocked and, anyone preaching its medical and psychological benefits after the hippie era was fighting an uphill battle. One consolation is that, just prior to his death, Albert was finally able to witness the first real clinical trials utilizing LSD in psychotherapeutic treatment since the early 70s. I’d like to believe that he passed over with a feeling of optimism within him, because of that. I’d also like to believe that Hofmann would appreciate and recognize Blomerth‘s book as something leaning much more toward the promotion of understanding and support for his discovery, than a lowbrow cartoon excerpt from some newfangled Anarchist Cookbook.

Alcoholics Anonymous co-founder, Bill Wilson believed in the power of LSD to assist in the treatment of addiction. That’s one reason why it’s so ironic that, if you head over to the DEA website right now, you’ll find it listed alongside heroin as a schedule I substance, “defined as drugs with no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.” Also in the schedule I category is cannabis, despite it’s proven medial usages and consistently growing legalization in this country. To put this into greater perspective, schedule II drugs — also deemed as having a high potential for addiction, but found to possess some level of medical benefit — include cocaine, PCP, and meth. [???] Shit just gets more absurd from there, with schedule III drugs — defined as having “moderate to low potential for physical and psychological dependence” — including ketamine and anabolic steroids, while schedule IV (“low potential” for abuse and “low risk” of dependence) consists of such drugs as Klonopin, Xanax, Soma, Valium, and Ambien. LSD is somehow considered to be more dangerous with a greater need for regulation than any of those other substances. And so is weed, as well as psilosybin. The good news is that, with a consistent growth in marijuana legalization and Denver residents recently voting to decriminalize psychedelic mushrooms, it proves that a schedule I classification isn’t, necessarily, a death sentence, after all.

The key to it all is information and research. Anyone that’s interested in donating to the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), can do so HERE. Similarly, the Heffter Research Institute, which claims Dennis Mckenna as a founding board member, focuses on “Advancing studies on psilocybin for treatment of addictions and other mental disorders, with the highest standards of scientific research.” Both are non-profits and invaluable resources.

Brian Blomerth’s Bicycle Day is available now through Anthology Editions.

Ooof! I almost forgot to drop the obligatory generic pull quote: “Brian Blomerth’s Bicycle Day is a wild ride!” [PRINT IT!]