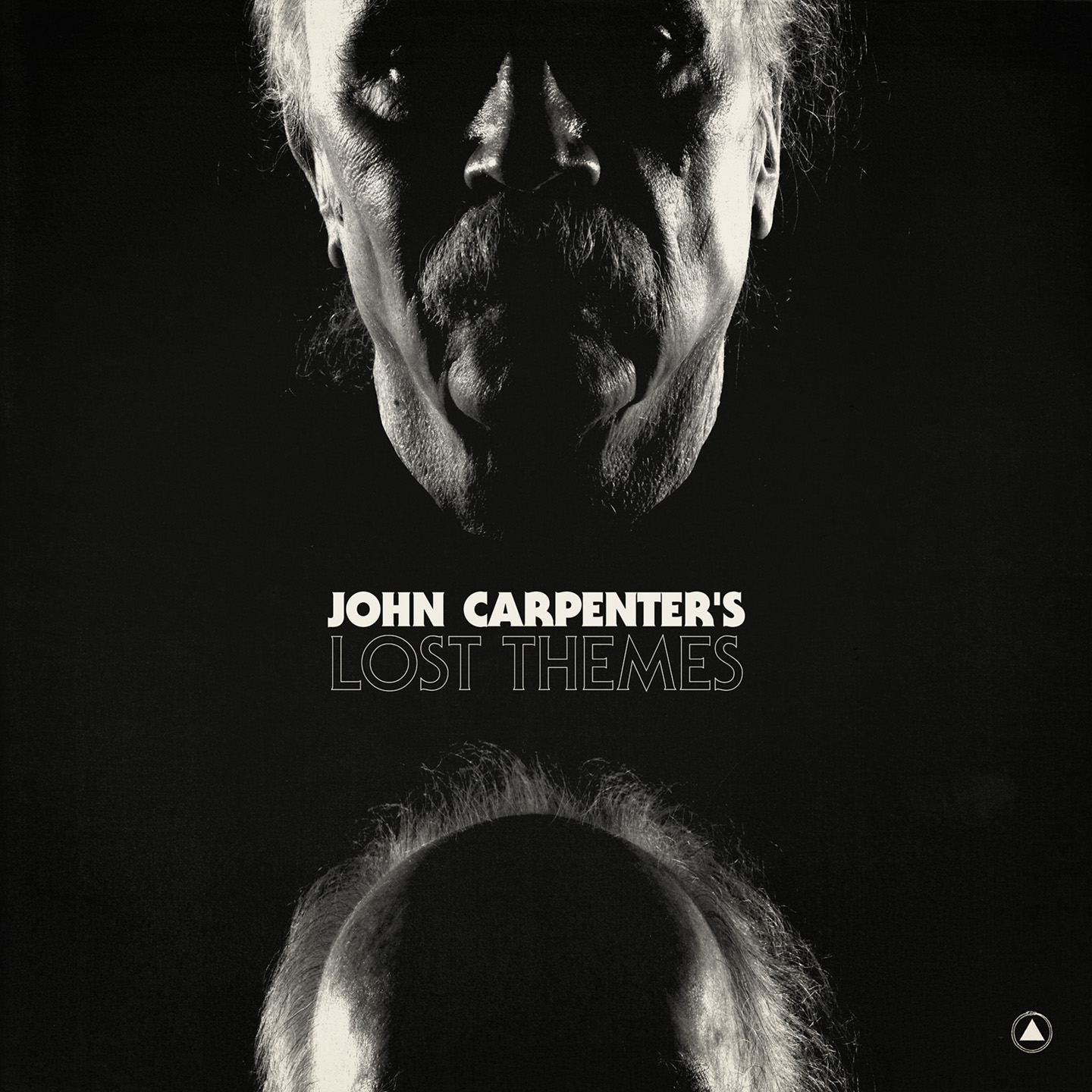

Watch The Video for “Night” from John Carpenter’s Lost Themes

After decades of creating classic scores for his own films, like Halloween, the master of horror has released Lost Themes, his first album outside of cinema

Considered one of the undisputed “masters of horror,” John Carpenter became somewhat pigeonholed after the tremendous success of Halloween in 1978, but used it as an opportunity to redefine the genre and create a legacy that will continue to be studied by aspiring filmmakers and aficionados for decades to come. It’s fascinating to consider how some of the most well-known and beloved works of a man who has been so widely imitated and has left such an immeasurable impact on the film world were originally panned by critics when they first came out. The legendary director — not to mention screenwriter/producer/editor/composer — has released a number of films that garnered their initial success as underground cult films, only acknowledged years later as the artistic masterpieces that they truly are. The Thing, for example, was rejected by both critics and fans so severely that, according to John, at least one article was even published with a headline suggesting that it might be the most hated film of all time. But, with such a forward-thinking, out of the box approach, polarizing reactions are to be expected and, in 2015, Carpenter‘s remarkably bold and distinct perspectives are still as relevant and needed as ever. As evidence of how the filmmaker’s reach has extended into other elements of our culture beyond just cinema, Mortal Kombat, which features a character modeled off of Lo Pan‘s lightning demi-god from Big Trouble In Little China, has become one of the most successful video game franchises in history, while famed street artist, Sheperd Faiery has built his OBEY empire in large part by utilizing concepts and imagery siphoned directly from John‘s 1988 sci-fi picture, They Live. Of course, no greater influence has been left by John Carpenter than the influences left on his peers in the industry and the up-and-comers that aspire to join them.

One such filmmaker who has been vocal about drawing plenty of inspiration from Carpenter in his own career is Robert Rodriguez (El Mariachi, From Dusk Til Dawn, Sin City, Machette), who invited John to appear as the very first guest on the inaugural episode of his program The Director’s Chair, last year. Airing on the El Rey network, which he founded, the show consists of Robert interviewing fellow filmmakers to give the audience an inside look on their process, providing a vantage point and perspectives that they often would not be privy to, otherwise. One of the most interesting aspects covered during their conversation pertained to Carpenter‘s work composing the music for his own films, a practice which Rodriguez, has also adopted. As the Escape From New York director explained, taking on that role of composer, in the early days, originally came out of necessity and a lack of funds to pay anyone else to write or perform the music. Without an orchestra at his disposal, he figured that, as long as he could get his hands on a synthesizer, then he should be able to pull out entire film scores on his own. Surprisingly enough, John‘s bold assumptions were absolutely correct, and his minimalist electronic soundscapes have not only become a key component in his own work, but have also defined a sound that endless others have fallen short while attempting to duplicate. With such potent narratives, inventive ways of presenting them, and an unmistakable, hypnotic aesthetic engulfing the viewer as it seems to gradually draw them right in through the movie screen, sometimes it’s far too easy to allow the director’s musical work to become overshadowed and overlooked. This is both because he has his hand in so many different, important elements of the creation process, and because his music is utilized so effectively that it melds effortlessly with the visuals, substantially enhancing final product. But once you stop to consider that John is the force behind such affecting and timeless tracks a the Halloween theme, his abilities as an artist become just that much more impressive. The fact that he scored that entire film in a matter of only 3 days and viewed that as a luxury — apparently, it was still 3 times as long as what he had available to score Assault On Precinct 13 — well… it’s something that I can barely even wrap my mind around. What’s so great about Carpenter‘s work is that, while he has definitely burned some truly unforgettable moments into celluloid, as well as our collective consciousness and pop history, it is the larger feeling that films like Christine manage to embody that can really penetrate and remain with viewers, indefinitely. His soundtracks have grown to become incredibly vital in the creation of these motion pictures; they are essence and the breath of these films.

In a post on VanityFair.com from February, the legendary auteur reinforced that point.

“While scoring started as a necessity, as I went on, it became part of my directing. It became a voice, a frame, for the movie. It’s very important.”

But while the music that he creates plays an integral role in his overall film making process, it has also proven to possess the ability to stand on its own quite admirably. The quoted Vanity Fair piece was published surrounding a career retrospective, titled John Carpenter: Master of Fear, which opened at BAM in February. Just 2 days prior, the Brooklyn-based label, Sacred Bones, also released Lost Themes, the director’s first full length album of new material specifically crafted without any intention of being used for the purpose of cinema.

Carpenter describes the creation process of his new album as follows:

“Lost Themes was all about having fun” […] “It can be both great and bad to score over images, which is what I’m used to. Here there were no pressures. No actors asking me what they’re supposed to do. No crew waiting. No cutting room to go to. No release pending. It’s just fun. And I couldn’t have a better set-up at my house, where I depended on (collaborators) Cody (Carpenter, of the band Ludrium) and Daniel (Davies, who scored I, Frankenstein) to bring me ideas as we began improvising. The plan was to make my music more complete and fuller, because we had unlimited tracks. I wasn’t dealing with just analogue anymore. It’s a brand new world. And there was nothing in any of our heads when we started other than to make it moody.”

Although it may have been, at least partially, born out of budget restrictions, the minimalism demonstrated in such movies as The Fog, Halloween, and The Thing have proven a huge benefit in John‘s ability to deliver scenes where the suspense is actually amplified by requiring/allowing the audience to “fill in the blanks,” so to speak. Carpenter has long been well aware that, if given the opportunity to interact with the content, our own imaginations are far more powerful than anything that he could ever hope to put on film. His musical scores play a large role in enhancing that dynamic, but as Lost Themes proves, they are equally effective, when operating alone. That being said, it’s difficult to disconnect the visual element from the sounds on this new effort, because, in the end, his soundscapes remain so visceral that it really does compel the listener to envision their own imagery, whether or not they remain in the abstract or evolve into something much more defined and specific.

In his brand new video for Lost Theme‘s closing track, “Night,” the music is so engaging that it can all but dissipate into the visual elements that it’s supporting and propelling forward. A 100% collaborative effort between co-directors Gavin Hignight and Ben Verhulst, the video successfully captures the essence of Carpenter‘s work. That is to say that the visuals do not overpower the music, as much as the music penetrates the visuals so fully and effortlesssly that it isn’t until well after you’re finished watching it, that you recognize that very little actually occurred in what feels like an incredibly engaging 3-minute 49-second experience. And even that which did occur, didn’t necessarily take place in any sort of physical “reality.”

Check out what Hignight had this to say about working on the new video and then watch it below.

“Upon hearing NIGHT by John Carpenter my head was instantly filled with these nighttime highway road dreamscapes. Someone or something, haunted, traveling the road alone in the late hours.

Our goal was to take that feeling and put it into a video that paid tribute to the film work of Carpenter but at the same time gave him a new world to play in… in this case literally through Virtual Reality.”