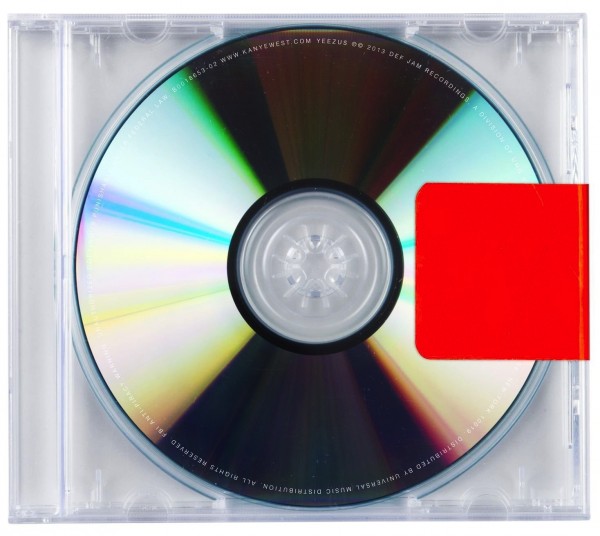

A God Complex, Yeezus, and Holy Shit

Eric DePriester analyzes Kanye West’s career up until this point, and expresses his opinions regarding the newest, controversial release, YEEZUS, in detail

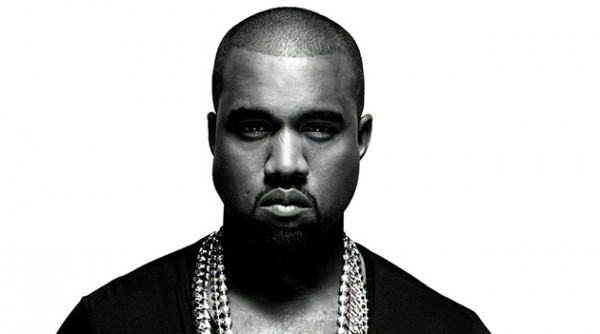

If we’ve learned anything about Kanye West over the last ten years, it’s that he doesn’t half-ass a damn thing. Every venture, every album, he goes all in, raising the stakes to absurd levels that most artists never reach over the course of their career. From the getgo–pushing his luck as an emerging producer for an album deal, mumbling his first single through a wired jaw, posing as Christ for Rolling Stone—Kanye didn’t necessarily take the most difficult path, he wandered through the weirdest and most personal way to radio dominance.

The instantly signature sound of The College Dropout [2004] could have been the blueprint for a flush career of mid-level hits and best selling albums, and, in the hands of more humble men, it would have been. Instead, Kanye brought indie film composer, Jon Brion in to co-produce the following Late Registration [2005], filling out his chipmunk squeaks and soul samples with rich orchestration and a wider range of sonic elements. He went one further on Graduation [2007], working heavy synths and rave worthy beats into the fold and stepping up his wordplay to match ambition.

Kanye could do no wrong, not in the studio; every album had club shaking anthems and industry leading sales to solidify his status as one of the top producers in the game. On the public relations front, however, Yeezy did everything that he could to undermine his undeniable talent: during a Katrina benefit concert, he went off script to insist that “George Bush doesn’t care about black people”; in what should have been a sign of things to come, he stormed the MTV Europe Music Awards stage and demanded that his “Touch the Sky” video was superior to the winning Justice vs Simian joint; instead of delivering a media ready starlet to partner with, he professed his addiction to porn and rapped about running through lines of groupies.

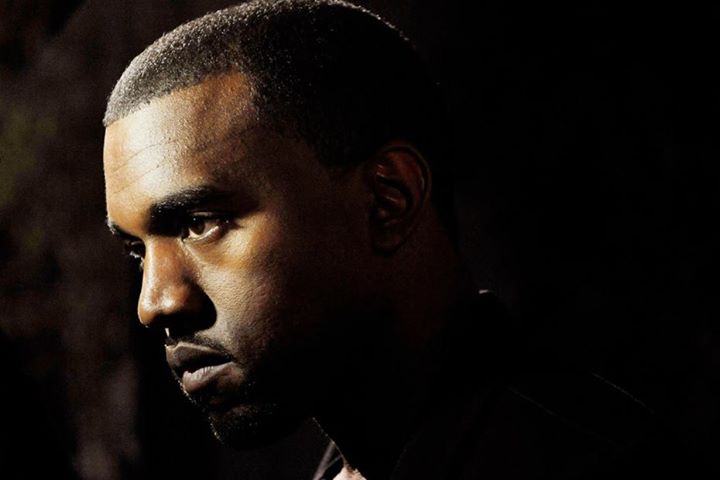

His dark streak leaked into his recording career with the release of his oddest record yet, 808s & Heartbreak [2008]. An album length descent into the most twisted trenches of Kanye’s mind, following a devastating breakup and the death of his mother, the disorienting synth fields and emo ready lyrics–delivered in robotic auto-tune–instantly alienated half of his of fanbase and divided the critics. While it pushed boundaries, adding a style previously unused in mainstream hip-hop and discussing topics considered taboo for emcees, it largely lacked discernible hooks and the playful wordsmithing that characterized the best of his work. With only one danceable hit, “Love Lockdown”, the other ten tracks detailed the depths of West’s emotional breakdown in a decidedly depressing way–it did not do well by Yeezy standards.

Though the album has its detractors, its existence can be justified solely by the fact that a star made a record that weird, that personal, and we listened. We were a bit freaked out, that’s to be expected, but no one was pissed off–not yet. The real backlash whirled up during the 2009 Video Music Awards, when Kanye interrupted human-Bambi, Taylor Swift, declaring her victory unjust, as “Beyonce made one of the best videos of all time.” Every part of the scene was nonsensical, from Kanye summoning righteous indignation at a meaningless awards ceremony, to Swift’s over-the-top defenders and their unending vitriol. Someone got drunk and made a fool of themselves at an awards show; really, isn’t that what we’re there for? No one cares who wins, especially not at an MTV award show. Their only significance is in gleaning a few water cooler talking points, which Kanye spits out in spades. We should have thanked him, not crucified him.

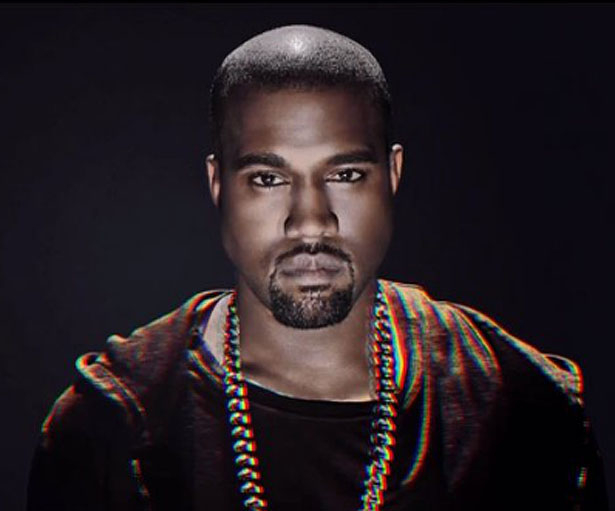

Stewing in the sting of everyone from Jay Leno to President Obama’s edged insults, Kanye took time off, far from the spotlight, to regroup and record his next album, My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy [2010]. A culmination of the styles that he’d explored throughout his still young career, the accumulation of more disparate influences, and a wealth of new personal narratives to detail in numbing excess, Fantasy stands as his personal high water mark and one of the finest albums of the two-thousands. While sales disappointed, critics rightfully responded with near unanimous adoration. He took the next two years as a victory lap, releasing an album of luxury rap (Watch the Throne) with Jay-Z, embarking on an arena tour, and then, hitting the media circuit with the new belle, Kim Kardashian.

Somewhere in that global thrill ride, Kanye built up a whole mess of angst, of deep seeded darkness, that needed an artistic exorcism. This brings us to Yeezus.

In a recent interview with the New York Times, Kanye confessed that Fantasy was an artistic compromise, a knowing play to public opinion, rather than his natural growth. The sound that he was most interested in–the future of his career, as he sees it–is a continuation of the electronic apocalypse explored on 808s, not the soul hooks on which he built his empire.

To realign with his vision and bring it to life, he holed himself up in a Paris apartment and brought together a diverse crew of collaborators, including Bon Iver’s Justin Vernon; young Chicago MC, Chief Keef; Daft Punk; TNGHT’s Hudson Mohawke; and even Skrillex, as a short term consultant. We know Kanye is an arrogant son of a bitch, barking the same belligerent confidence as Kobe Bryant, and while it can be grating, that swagger is necessary for performing at such a level. Extending the parallel, Kobe became a transcendent basketball player when he admitted his limitations and enabled more contributions from his teammates, in an effort to progress his game; Kanye did the same.

There have been accusations of artistic vampirism, that Kanye chopped and screwed over a few too many sounds without due credit, that perhaps his originality is borrowed, not earned. Whether or not the claim rings true is irrelevant. As long as his songs aren’t copped wholesale–a reality that I’m confident endorsing, given the individual insanity injected into every track–West is merely following the tradition of hip-hop and most artistic mediums. Influence and partial reproduction begets embellishment and, in the best cases, true creativity. Very few pieces come to life in a vacuum, rather they are nurtured by following forebearers and consulting contemporaries.

Let’s examine another parallel: David Bowie. After extending psych folk, glam rock, and plastic soul to their logical conclusions, he retreated to continental Europe–first in Paris, then in Berlin–to record a series of dark, disturbing albums that drew heavily from modern Krautrock, and bewildered fans and deejays eager for more hits. To craft the minimalist, electronic sound that he envisioned, Bowie brought along bandleader, Carlos Alomar; trusted producer, Tony Visconti; audio weirdo, Brian Eno; King Crimson guitarist, Robert Fripp; and neighborhood threat, Iggy Pop, among others; each contributing bits and pieces to the overarching narrative, the detailing of Bowie’s disconnect from the world at large, and never ending conflict with the beast within. The argument can be, and has been, made that his development was too derivative on Neu!, Kraftwerk, Can, and other German acts, but Bowie took the movement that they started and brought it to new artistic heights, producing work so powerful that it pardoned any claimed sins of influence.

Yeah, it’s a leap from Low to Yeezus, but not as far as you’d think. Recording processes aside, both albums see their creators haunted by the hallmarks of fame and stifled by expectation, choosing to break new ground by co-opting the avant-garde, instead of retreading proven paths. Until we amass a few decades of distance, it’s unclear whether Kanye’s creation will have anywhere near the impact of Bowie’s; we can distract ourselves in the meantime with a truly engaging and raw piece of music.

The album opens with “On Site,” a call to arms and declaration of intent. Between Kanye professing how little he “give[s] a fuck,” the squelching space production of Daft Punk, and the jarring choir sample intrusion, the song serves as the blueprint for what follows. Next up is “Black Skinhead,” the closest West has come to punk; a barreling ego booster with a hypnotic drumline, equal parts Marilyn Manson and Gary Glitter. In a trailer for his upcoming film, The Wolf of Wall Street, Martin Scorsese soundtracked Leo DiCaprio’s substance and cash fueled rise and crash with “Skinhead,” Kanye’s tribal screams, sinister bass, and repeated commitment to “living in the moment” synching up seamlessly. Despite the fit, the song would have matched just as well to a post-apocalyptic biker gang flick.

Yeezy amps up the hubris with “I Am A God,” a screeching, stubborn rejection of earthly bounds. Over a pounding Daft Punk beat–the third in a row–Kanye rails against slow service at Parisian cafes, questions society’s definitions and expectations, and casually drops conversation with Jesus. It’s batshit crazy, wildly abrasive, and catchy as hell; concluding, of course, in horror movie screams and the first drop-in from Justin Vernon, the bearded mastermind behind Bon Iver.

In the ramp-up to release, Kanye arranged a series of projections of fourth track, “New Slaves” onto landmarks and notable buildings across the globe. While there’s no official single, this hook-laden series of accusations–condemnations of racial and economic inequalities–is, oddly enough, the closest that Yeezus has to a commercial hit. The throne Rome theatrics of the chorus and buzzworthy lines–“There’s leaders and there’s followers, but I’d rather be a dick than a swallower”–recall Kanye’s first single off My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy, “POWER,” but here he brings it to the people, instead of hoarding it all himself. Triumphant, defiant, blowing full steam towards total annihilation, Kanye doesn’t throw down the gauntlet, he smashes it against the wall. After raining down fire, a heavenly sample from a 60s Hungarian psych band drops in and Yeezy spits some auto-tuned falsetto, easing into Frank Ocean’s angelic croon–an ascending, hopeful end to a rap polemic destined for an Occupy rally.

Following a night of rage, “Hold My Liquor” picks up in the darkest hour before morning’s break. An unlikely cross-collaboration of Vernon’s haunting warble and Chief Keef’s slurred contempt (both auto-tuned), the woozy last stand of the id leads into a pornographic reduction of 90s R&B, “I’m In It.” The spiritual sequel to Fantasy’s “Hell of a Life,” Kanye delivers some of his most cringe-inducing lyrics alongside another dose of Vernon–in full belt mode–and indiscernible reggae inflected refrains courtesy of Assassin, a Jamaican MC. Once the lust grinds down, Kanye busts out the real wordsmithing: “My mind move like a Tron bike, pop a wheelie on the zeitgeist”; “They be balling in the D league, I be speaking Swaghili.” Unfettered at last, free of the realities that stifle creativity, Kanye is himself–playful, cocky, and clever as shit.

Which leads us to the centerpiece of the album, “Blood on the Leaves.” The first voice that you hear is Nina Simone’s, a piercing lament sampled from her cover of “Strange Fruit,” the classic outcry against lynchings, first popularized by Billie Holiday. Working with such revered source material, one would assume that Kanye would tread lightly, but one would be entirely incorrect. Bringing back the emotional content and confessional feel of “Runaway,” he runs down a disastrous relationship with a groupie and all of the risks inherent in playing conductor to a ho train. Oh, and he drops a booming TNGHT beat, a minute in, that entirely dements proceedings, lifting a melancholy meditation into a head wobbling banger.

Maybe it’s offensive to suggest that these topics are on the same plane, much less part of the same song. While the absurdity may go too far, it’s that exact lack of reverence that makes Kanye so great. By placing all of his potential influences on the same plane–hip-hop, soul, religion, love, sex, EDM, fame… everything that infiltrates his head deep enough to elicit response–he achieves that rarified progression of post-modern disregard for pre-ordained meaning into truly independent and innovative work. Everything is source material for art, for individual expression, regardless of previous connotations. It may get ugly at times, distasteful even, but that’s a shock we’ll have to stomach in the name of artistic exploration.

Winding the record down to a close, “Guilt Trip” plays like 808s & Heartbreaks 2.0, the warped vocals, space blips, and minimal orchestration recalling the finer moments from that spectacular miss. He plays it a little safer with “Send It Up,” the fourth Daft Punk produced track, that makes clear its intentions–if the thumping beat and siren didn’t already–with Kanye’s repetition of “in the club” over his first five or six lines. Finally, soul sweetness makes a full fledged comeback with “Bound 2,” a playful ode to like, love, and losing yourself in the chase. As the faded sample keeps cementing, Kanye is not bound to a particular woman, he’s “bound to falling in love.” He won’t always be true, he won’t even always try, but he’ll tell you when he fucks up and he won’t apologize for shit. It’s absurd, arrogant, and honest; no, it’s infuriating. Do we hate him? Adore him? Throw him in a psych word, or give him a parade?

Charlie Wilson, lead singer of R&B/funk legends, The Gap Band, gives a few Ziggy Stardust–lite last words to finish out the album: “Grab somebody, there’s no leaving this party without someone to love.” His funkified, possibly insane, voice of reason urges the listener to follow Kanye through unhinged self-indulgence, the only clear road out of brutal reality. Much like Bowie ended “Rock and Roll Suicide” with “Just turn on with me and you’re not alone,” both artists conclude their records with deep wells of hope and the passed-down impetus to chase greatness, lifting their audiences and setting them on the track to something better.

Maybe Yeezus saves, or maybe his arrogance damns. Either way, it’ll be a hell of a ride with Kanye in the cockpit.

excellent stuff. i agree completely and have been thinking that yeezus represents the first step of “leaving home” that visionaries like bowie, lou reed, or tom waits have embarked on, trajectories that completely fulfill consumer and critical expectation before leading elsewhere and getting reeeeally interesting. it’s from this point where i’ll be most stoked to see his career go.