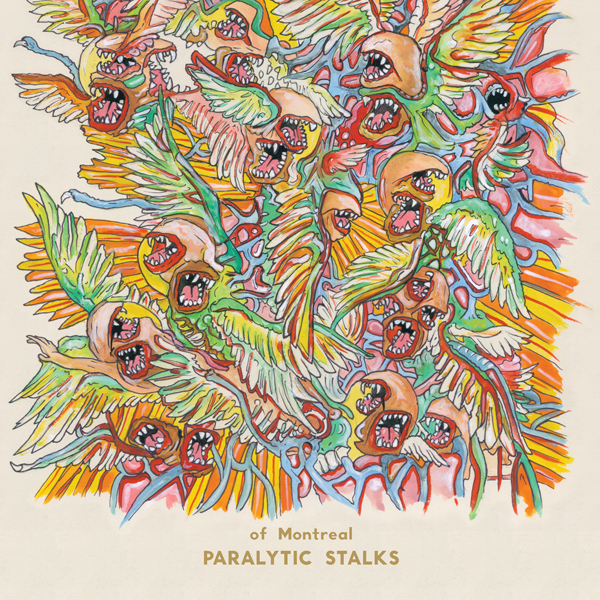

Disconnect the Dots – A Review of Paralytic Stalks by Of Montreal

Analytic talks about Paralytic Stalks. The latest release from Kevin Barnes and Of Montreal reviewed

In late August of 2009, I picked up Of Montreal’s Hissing Fauna, You are the Destroyer? a couple of days into an ill-fated trip with my wife. Between losing our ID’s and the fact that I had decided (for the both of us) to skip the planning process for the trip, we had as much chance of having a good time as a dying man at a bar mitzvah. I had this romantic notion that we would drift for a few days and land wherever the road seemed to be taking us. For almost any Seattleite, this “plan” is actually some weird code for “let’s go to Portland.” We got to the city pretty late. Without a useable ID between the two of us, we were turned away from almost every hotel in the city. It’s also worthwhile to mention that, at this poin,t we had only been married for two days. Eventually, we found a hotel with a tenant so mousy that I managed to intimidate my way into a room. The complementary soap smelled like fish sauce. The next morning, we stopped at a record shop before leaving the city, where I was drawn to the stained-glass graphics of the Hissing Fauna, and thought some electro-pop might smooth over this honey-moon-gone-wrong. This also happens to be a good way to describe Of Montreal’s new album, Paralytic Stalks.

In late August of 2009, I picked up Of Montreal’s Hissing Fauna, You are the Destroyer? a couple of days into an ill-fated trip with my wife. Between losing our ID’s and the fact that I had decided (for the both of us) to skip the planning process for the trip, we had as much chance of having a good time as a dying man at a bar mitzvah. I had this romantic notion that we would drift for a few days and land wherever the road seemed to be taking us. For almost any Seattleite, this “plan” is actually some weird code for “let’s go to Portland.” We got to the city pretty late. Without a useable ID between the two of us, we were turned away from almost every hotel in the city. It’s also worthwhile to mention that, at this poin,t we had only been married for two days. Eventually, we found a hotel with a tenant so mousy that I managed to intimidate my way into a room. The complementary soap smelled like fish sauce. The next morning, we stopped at a record shop before leaving the city, where I was drawn to the stained-glass graphics of the Hissing Fauna, and thought some electro-pop might smooth over this honey-moon-gone-wrong. This also happens to be a good way to describe Of Montreal’s new album, Paralytic Stalks.

The eleventh full-length studio album from the band, Paralytic Stalks stands out in some interesting ways from the group’s usual methods. Kevin Barnes, Of Montreal’s brain-daddy, is a man who likes to work alone. I found Hissing Fauna to have a sound that is very lonely—a term that I would not want to be confused with “empty”.

Barnes’ music is a wedding cake of layers; but every layer is of the same flavor and texture. His sense of scale and interval is very specific to him, so that when Kevin Barnes writes a section of music, he leaves behind a distinct stylistic fingerprint. It’s evident—without reading the billion interviews in which he confesses to this M.O.—that he is writing and performing all the parts himself. There is not the sense of depth that comes from different minds composing the parts for their own instruments, with their own sensibilities. There is one sensibility to Of Montreal’s composition. It’s a very asexual approach to music making: creating a culture of clones, and conducting them in a perfect 16-part harmony. This has been the case up until now.

For the first time, Barnes has brought in session players, and even out-sourced some of the more orchestral arrangements to a few partners in composition, including Kishi Bashi (Jupiter One, Regina Spektor, Sondre Lerche). His explanation for the change is that, simply enough, he brought in people to play the instruments that he can’t play. However, even as a larger trend, Barnes has slowly begun to favor organic textures over the stiffer electronic sound of his earlier work. As LCD Soundsystem would sum it up, “all the kids are selling their sequencers and buying bass clarinets.”

Despite the external instrumentation, Barnes kept the content Paralytic Stalks closer to himself than previous works. Barnes doesn’t take on a concocted persona on this album; he is singing as himself. His narrating voice has been a sort of loch ness monster throughout his career, surfacing, vanishing, and being confused for things that it’s not. He claims that he sings as himself on sections of Hissing Fauna, but I’m not sure that I believe him. I suspect that Kevin Barnes leaves the whole “suffer for fashion” bit to his alter ego, “Georgie Fruit” (evidenced by his overwhelmingly normal appearance on Jimmy Falon). He, as Kevin Barnes, is no more honest about the world that he perceives than his alter egos, but he has a distinctly different attitude. His constructed identities read as attempts to force new perspectives on himself—as the psalmist grabbing himself by the collar and commanding, “make a joyful noise!” In contrast, Barnes as Barnes is free to observe and comment without implementing the discipline of second-guessing.

All this to say, the paradox of an externalized sound coexisting with internalized content finds singularity in the neurotic, dizzying mood of this new album. As it details the intense vulnerability of intimate relationships, the terrain this album covers includes mental abuse, codependency, horrible accidents, crippling melancholy, and the ultimate dissolution of all sociological institutions. From beginning to end, you can expect a spinning cabaret of the mental anguish of being known all too well. Ironically, the frontman’s response to such vulnerability is to itemize it and publish it for the public—including myself, right now—to dissect.

Barnes borrows the album’s introduction from himself. Sounding remarkably similar to the first seven seconds of The Sunlandic Twins (2005), Kevin brings in the album with a whirling abstraction—just enough to let you know that you can expect a fairly impressionistic sound. After this initial nod to his former works, the sounds that follow are new to the musicians’ pallet. The first movement of the album is a brooding beat that moves your head for you (in fact, most of the movements of the album can be describe by which involuntary body movement it causes). “You speak to me, like the anguish of a child doused in flames” he sings, summing up the narrative of this album in a perfectly Virgilian chorus. This is his thesis, which envelopes the following hour of “torment(ing) each other”.

The single of the album, “Dour Percentage,” plays out like an easy listening song from the seventies. With a melody that recalls Diana Ross and a textural flute that approximates some of Sufjan Stevens‘ more extraterrestrial arrangements, this song is the chimera’s most publicly presentable head. Although straying from the 40-day wilderness that the rest of the album simulates, “Dour Percentage” is no Judas, and does not betray the complex abusiveness of the album for a bag of silver royalties. I have, though, always admired Barnes‘ willingness to “sellout” (IE his Outback ad campaign). It gives him a relatable, working-class edge over more puristic artists—but this song is not a great example of his commercial sensibility.

In a recent experiment, Kevin sought to determine the solubility of Elliot Smith in an Of Montreal composition. The results of the inquiry produced the first twenty seconds of “Wintered Debts.” The allusion is easy to miss, as it is short lived and indeed dissolves into Of Montreal’s typical asexual harmonies; but for those twenty seconds, the songsmith plays Virgil, taking us into the Inferno and putting us in conversation with our dear, beloved sad-boy-singer. Barnes-as-Virgil-as-Smith haunts us using whispery “Needle in the Hay” vocals and Roman Candle guitar. Channeling Smith carries some of his own relational implications. I’m not one for celebrity conspiracy theories, but, in the context of Paralytic Stalks, it seems interesting to bring up that Smith’s live-in girlfriend is an unofficial suspect in the mystery surrounding his stabbings. After all, Paralytic Stalks is about the kind of love that will stab you twice in the chest and then misspell your name on the forged suicide note.

But sure enough, Smith is only channeled for a mere moment and then, is exorcised into a vast pop odyssey revolving around “too much bitterness”. The through-composition takes a surprising country turn, introducing slide guitar and a two-step beat that eventually, gives away to the sound of crippling depression. Bringing in a boldly abstract movement, Barnes indeed has composed the sound of circular reasoning. Sandwiched between songs that are best described as pop, this section of the new release seems to depict the manic and the depressive.

The next ten minutes are a portrait of the artist as a deaf-mute on the couch, unresponsive and absent. It is a fever dream that you don’t know how to wake up from. As a mechanism of this album, “Exorcismic Breeding Knife” definitely performs. The feelings are all there. It is however, almost unlistenable. What Barnes does not quite succeed at is infusing this movement with enough ethos to persuade the listener away from the “skip-track” switch. I am glad that he included it in the album—it goes there. I, unfortunately, don’t want to follow him there and maybe that’s on me.

But in the end, I guess this is the stuff of love. At its most romantic, it approximates the demon, codependence. At it’s most flaccid, it’s a cycle of insecurities that get exposed on repeat. “I love how we’re learning from each other” though. My dad explains love as a set of gears that don’t quite match. The metaphor gets a little overextended, but the truth of the matter—the same truth that Kevin Barnes is after—is that love is the process by which we are ground down to the shape of our other. It must be a loss of self, if it’s meant to be successful. The flying of sparks is from the immense friction of two different metals touching at high speeds.

Maybe there is something unhealthy about feeling bound to a person that is a continual source of pain—for the source of “200 thousand years of viciousness” to also be “the only one that ever put money on me”. It is self-destructive for sure; but to take it out of the realm of poetry and inject it into real life, consider this: Barnes’ wife Nina is one of the brains behind the Of Montreal stage production. Her signature is on this album as well as Kevin’s—a mutual accusation and apology. As they partner in putting on the abusive-relationship show, they simultaneously exhibit a portrait of a highly functional couple, perfectly aware of how twisted and “dehumanizing” love actually is; and choosing it anyway. Somehow, the honey-moon-gone-wrong is still the better option for some people.