JOURNEY MAN: AMON TOBIN’s ISAM [part 1 – The Album & Artwork]

ISAM, the latest effort by Brazilian-born electronic mastermind, Amon Tobin, begins with the static-speckled mutated warps of a spacecraft’s tractor beam pressed into vinyl and played in reverse. As they whiz past -one by one- like radioactive mach 5 boomerangs, there’s a restrained compression to the short, quickly intensified spurts and it’s like being in a wind tunnel full of fluttering moths, while having close calls with a mob of light-cycles. That is, of course, if there was a halogen model (it retains that ominous hum of fire-prone lighting fixtures). While pockets of oxygen continue to get sucked out through the mouth of a vacuous wormhole, a slight framework of tones chime in all around, providing a new airy dimension to the aural environment. These muted bells are sprinkled in or bong at various depths, illuminating like a smattering of fire flies. They resonate briefly and disappear as quickly as they arrive. Like dying stars, by the time you grasp the image of each little blooming glow, it’s already gone; evaporated and cloaked by the murk of dark matter. The rattle of loosely tightened machine bolts is introduced and glitches sporadically. The aquatic blurble of a submerging bathysphere slips in. Intermittent bursts geyser up to temporarily spray-paint a fiber-optic aurora borealis in as a back drop. At this point, we’re still only a little more than a minute into “Journeyman“, the lead off track from the new full-length. The rest of the track continues to unravel slowly with bubbling crudes, shuffling mechanical insect legs, drops in atmospheric pressure, sizzling magma, and cannon blasts from pneumatic tubing. It’s a fucking trip and the imagery that it summons is as vivid as it is abstract. Toppling -choloroformed face first- through a looking glass, sucked through a folding tesseract, and spit into a dusky majestic forest that extends to the edges of the asteroid that it’s floating on. There’s a segue into this world, but it’s so effective that you find yourself fully engulfed by it before you know what’s happened. The most cliche, yet effective, comparison would be to the peaking of an LSD trip. Tobin slowly draws you out of your skin to the point where you can almost feel that familiar tightening of your cheek bones, while your chest and head fill with helium. Then you’re off; half zipping like Akira through a cybernetic metropolis and half floating motionless in the thick ooze of a sensory deprivation tank. It’s a difficult task trying to describe the audio collages that Tobin constructs without the use of analogy and emotional references. This is mainly because there are not “real” instruments on this album at all and the familiarity is much more emotional than logical. Crafting new sounds, stacking them, weaving them together, painting the equivalent of a Roger Dean YES album gatefold with nothing but audio… It’s definitely an ambitious project. And, as if the music wasn’t enough, Tobin‘s found a way to match it with an equally ambitious presentation; including an art exhibit and the first real “live show” that he’s ever attempted to put together.

ISAM, the latest effort by Brazilian-born electronic mastermind, Amon Tobin, begins with the static-speckled mutated warps of a spacecraft’s tractor beam pressed into vinyl and played in reverse. As they whiz past -one by one- like radioactive mach 5 boomerangs, there’s a restrained compression to the short, quickly intensified spurts and it’s like being in a wind tunnel full of fluttering moths, while having close calls with a mob of light-cycles. That is, of course, if there was a halogen model (it retains that ominous hum of fire-prone lighting fixtures). While pockets of oxygen continue to get sucked out through the mouth of a vacuous wormhole, a slight framework of tones chime in all around, providing a new airy dimension to the aural environment. These muted bells are sprinkled in or bong at various depths, illuminating like a smattering of fire flies. They resonate briefly and disappear as quickly as they arrive. Like dying stars, by the time you grasp the image of each little blooming glow, it’s already gone; evaporated and cloaked by the murk of dark matter. The rattle of loosely tightened machine bolts is introduced and glitches sporadically. The aquatic blurble of a submerging bathysphere slips in. Intermittent bursts geyser up to temporarily spray-paint a fiber-optic aurora borealis in as a back drop. At this point, we’re still only a little more than a minute into “Journeyman“, the lead off track from the new full-length. The rest of the track continues to unravel slowly with bubbling crudes, shuffling mechanical insect legs, drops in atmospheric pressure, sizzling magma, and cannon blasts from pneumatic tubing. It’s a fucking trip and the imagery that it summons is as vivid as it is abstract. Toppling -choloroformed face first- through a looking glass, sucked through a folding tesseract, and spit into a dusky majestic forest that extends to the edges of the asteroid that it’s floating on. There’s a segue into this world, but it’s so effective that you find yourself fully engulfed by it before you know what’s happened. The most cliche, yet effective, comparison would be to the peaking of an LSD trip. Tobin slowly draws you out of your skin to the point where you can almost feel that familiar tightening of your cheek bones, while your chest and head fill with helium. Then you’re off; half zipping like Akira through a cybernetic metropolis and half floating motionless in the thick ooze of a sensory deprivation tank. It’s a difficult task trying to describe the audio collages that Tobin constructs without the use of analogy and emotional references. This is mainly because there are not “real” instruments on this album at all and the familiarity is much more emotional than logical. Crafting new sounds, stacking them, weaving them together, painting the equivalent of a Roger Dean YES album gatefold with nothing but audio… It’s definitely an ambitious project. And, as if the music wasn’t enough, Tobin‘s found a way to match it with an equally ambitious presentation; including an art exhibit and the first real “live show” that he’s ever attempted to put together.

In the early days, Amon constructed groundbreaking works like Bricolage (1997) and Permutations (1998), which were jazzy, downtempo, drum n bass-heavy releases with vinyl samples full of shambolic jazz kits and breakbeats. Tobin‘s choice of titles are always telling and, by the time that albums like Supermodified (2000) and Out From Outwhere (2002) were released, the samples were becoming so altered (“modified”) and were becoming so unrecognizable that it was sounding a lot more like the artist was siphoning his material directly from the outer limits of the cosmos, rather than mining it from anything terrestrial; let alone, dusty old jazz records. From there came remixes, compilations, a “soundtrack” to the highly successful Tom Clancy video game, Splinter Cell: Chaos Theory (marking a shift into the use of self-created samples), and another soundtrack for a Hungarian film about competitive “speed eating” and taxidermy ( the album cover art is of a shack-dwelling man shooting flames from his dick). The next proper follow up for the Ninja Tune golden boy, however, wouldn’t arrive until 2007‘s FOLEY ROOM. Being a full 5 years since his last “real” studio album, I wasn’t even aware that it was on it’s way until I accidentally stumbled across it. It was immediately engaging and I listened to it at least a half dozen times before learning that Tobin had approached the project with the intention of utilizing nothing but field recordings, in the tradition of the foley artists that create sound effects for film. The CD came with a bonus DVD documenting Amon as he collected the samples from sources like roaring caged lions, electric toothbrushes on banjos, and buzzing swarms of hornets in a balloon made of foil. These effects were masterfully stacked, mixed, and blended, achieving much more than mere novelty, but actually exposing the musical potential for such things as motorcycle engines and splashing water. Realizing that there was a missing element, Tobin eventually recruited the talents of the legendary Kronos Quartet to fill out the sound by supplying the eerily haunted string arrangements, breathing into the songs with a wispy undertone of beautifully hypnotic doom. Now, with his obsession to constantly move forward and continue to explore new avenues in sound, the electronic innovator has continued to alter his creation process and push his sampling/production methods even further with the release of the multi-media ISAM project earlier this year.

The video above demonstrates Tobin‘s use of a super wacky, hi-tech fingerboard/midi-controller known as a “Haken Continuum” to create the sounds for ISAM. You’ll notice that he’s sampling simple items around his studio before mutating and blending them to create something new and multi-dimensional. This time around the man seems to have found ways to work smarter, instead of harder (although, any time that he saves is, undoubtedly, channeled back into some other element of tedium for the project). Instead of hunting out field recordings from obscure locations, the producer recognized that, if those sounds created by various unorthodox outside sources could be harnessed for melodies and rhythms, finding new life in a musical context, then any unassuming item that’s already within reach in his studio or simply sitting on the coffee table in his living room should be able to be utilized to operate just as well. From there, the noises were processed, often being pushed through multiple filters each. The above video shows such examples as a chair creak being synthesized or the ding of light bulbs being morphed into the twang of another sample. Once the sounds of those original items are collected, they can be intricately manipulated through the continuum finger board.

The tracks on ISAM are definitely new explorations in sound and song structure, but they are meant to be listened to and enjoyed, first and foremost. What I mean is that it is a project that is much more about the final product than the gimmick behind it’s construction or the individual elements that went into creating it. Anyone can play you a recording of railroad nails being hammered in and instruct you to find the rhythm in it, but Tobin is a composer at heart, aside from being an audio scientist. His means of creation are as much a method to construct elaborate soundscapes that listeners can interact with and become submerged in, as they are opportunities to indulge his own personal needs to expand his skill set and tinker with whatever newfangled contraptions that he has access to.

The song “Mass and Spring” (falling dead center at track #7 of 12) is one of the most fragmented start and stop-style offerings on the album, often coming through like a game of Sonic the Hedgehog, only if the main character was stuffed full of ambien and dramamine. Propeller-esque shuffling is catapulted forward, only to reverse like a batarang. It could often be difficult to decipher the individual field recordings on Foley Room, but they still seemed slightly more untouched and there were moments where an engine rumble or lion roar was definitely recognizable as such. For the most part, every noise is used to meld into and enhance the music -for both projects- but if any of the samples do expose themselves and stand apart as individuals within the singular blanket of woven sound on ISAM, some of those moments definitely appear in “Mass and Spring“. Busted jack-in-the-boxes pop up at random; their loosened heads fling off and plink down through bottomless wells. Racketballs richocet off of plaster and sink into vats of dense pudding after being launched from a bug zapper. An antique elevator strains it’s weathered cables and the echo of rusty harp strings vibrate from the damp basement level and up through the hollow shaft. It’s beautiful and dark, like the rest of the album, like the album before it, and like select moments on every piece of work that’s preceded it. It’s entirely new, but it still has it’s creator’s stamp all over it. It’s oddly foreign, but even more oddly familiar.

[audio:http://monsterfresh.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/7-Mass-Spring.mp3]Early on (April?), Amon Tobin uploaded a full soundcloud stream of ISAM with written commentary of the album throughout. Of this particular track, Tobin states the following:

“mass and spring is based on acoustic modelled ‘made up’ string instruments that behave very strangely when played due to the conflicting physical properties I’ve assigned to them.“

He continues with this train of thought in other comments on the stream, referring to the fictional instruments that he’s envisioned in his own mind.

“no samples featured on the album instead sythesised instruments are combined with multi-sampled instruments all of which are playable.“

“I love the idea of playing futuristic non existent instruments built a high level of detail in their construction but playing them actually quite badly : )“

Also featured on “Mass and Spring” are the “ooohs” of a “female” voice. This voice also appears in the previous track “Wooden Toy“, with the “woman” singing actual lyrics. Later, a separate feminine vocal appears on “Kitty Cat” (track #9). Even prior to this, delicate “aaahhs” are introduced as early as the second track, “Piece of Paper“, continuing into “Goto 10” (track 3), with the addition of subtle “doot-do-dos“. The “aaahhs” return later, buoying throughout “Lost & Found” (song #5) and adding an eerily angelic atmosphere to the track, but it isn’t until “Wooden Toy” that we actually hear it as an undeniably human voice beckoning our attention to actual verses. Before that point, the vocals are little more than a additional instrumentation and/or used as accents, providing a slightly less robotic counterpoint to the various hydraulics, recoils, glitches, sonic thrusts, ruptures, and teleports that they assist in adhering together.

[audio:http://monsterfresh.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/6-Wooden-Toy.mp3]A lot of electronic musicians will try shit like this, throwing a random -generally female- vocal into the mix on an otherwise instrumental effort. It’s similar with instrumental hip hop records, except that those generally have one of the artist’s pals stepping in to add a speedbump by awkwardly rapping over a track, while female singers typically sidetrack these sorts of releases by taking them into more dancey, house music-oriented territories. In both circumstances, if done poorly (as they usually are), the introduction of an outside vocalist can really toss a temporary twig into the spokes of an otherwise fluid release, forcing it to attempt to regain it’s continuity after a disorienting hiccup. Introducing multiple separate voices at different points can increase that possibility of disjointedness further. One of the rare situations that such accompaniment actually works amazingly well is on Daedelus‘ Righteous Fists of Harmony EP, with the artist’s wife and Long Lost collaborator, Laura Darlington, appearing on various tracks seamlessly. This is likely due to their close knit, intimate working relationship and understanding of each other’s abilities as artists. Tobin finds a similar benefit with ISAM, which manages to become another such successful undertaking… almost. I don’t mean that it doesn’t work, because, from the first time that I heard the album, I was incredibly impressed and surprised by how the introduction of vocals could benefit Tobin‘s tracks so remarkably. The only reason that I use the term “almost” is because -previously unbeknownst to me- there technically isn’t any “accompaniment” or “outside vocalist” on the album whatsoever. In fact, both of the “women” that appear on ISAM are nothing more than Amon himself, only with his voice pumped full of a convincing dose 0f electronic-based estrogen through some sort of SRS-inspired production wizardry.

Amon says the following of “Goto 10“:

“my own vocals synthesised and gender modified here.“

…and “Lost and Found”:

“My own vocals analysed and gender modified.“

Regarding his singing on “Wooden Toy“, he states:

“so here we have the first of two imaginary characters I’ve featured on the album. I performed the vocals which were then synthesised and turned into a female.“

Then, for “Kitty Cat“, he provides the following insights:

“here’s the second made up character vocalist on the record. this time she’s supposed to be older and has an american twang like some folk singer.“

“probably best to ignore the words.. they are pretty silly and more of a necessary biproduct of the experiment with synthesising vocals to create convincing characters.“

The other largely impressive and immediately noticeable aspect of ISAM is the severe lack of drums. This is, perhaps, the biggest difference from the composer’s early work that relied so heavily on the beats to create a skeleton to drape the doom-laden flesh across. You can’t spell “drum n bass” without the drum. This release demonstrates the musician evolving into a completely different animal.

There are definite rhythms on the album, but they are far less overt than that of a wily jazz break or even a schizophrenic drill n bass gatling attack. Moments of heavy impact do appear, like cannon balls thumping into a wet lawn, but even during these instances, no “real” drums or drum samples were ever utilized. It’s not only impressive that he’s able to pull off such an undertaking, but also in the multitude of ways that he’s been able to make it work so fantastically. The song “Calculate” relies primarily on glistening tonal bells and warm computer-like blips to create its’ framework over the occasional minor click and understated intermittent electrical surge. “Bedtime Stories” threads the rustling clink of metal thumb tacks in a mason jar throughout the discharge of toy rockets, the reeling zip of a penny racer, and enough atmospheric pressure flux to make your ears pop. All of this is supplied with a lathering of gentle bells from a music box lullaby. “Night Swim” is a thoroughly cinematic piece, evoking images of stepping barefoot and sopping wet across jagged rocks to take shelter from the increasingly brisk night in a dark musty cave. The music itself sounds like you’ve tucked your ears under water while listening to a recording of wind chimes through speakers that occasionally show static evidence that they’ve been slightly blown. Or, as Tobin puts it…

“grains and fragments cluster together to make something that resembles a beat.“

and…

“fragments disassemble and they fall apart again.“

As with the Miles-esque approach to “the notes you don’t play“, much of the structural elements on ISAM are formed by the moments of absence or the spaces between the more defining sounds. At other times, it’s the sheer and consistent amplification or deceleration of one sound in relation to those adjacent to it. This is never more apparent than on the lurch and collapse of the track “Surge“. Many of us might have memories employing a similar approach to formulating rhythms, by rapidly twisting back and forth on the volume dials of your parents radios, as makeshift childhood DJs.

The last track on ISAM, “Dropped from the Sky“, is like softly hang-gliding past the ends of physical space and into stark whiteness, only to see a new extension of uncharted Earth being created in real time all around you. The outline of rigid cliffs and majestic peaks sharply cut through the nothingness and come into focus. They are coated with rich moss and wild flowers that, just as swiftly, sprout in blankets across their surfaces. First there’s an anonymous mist and then the waterfall that didn’t even exist a moment before. Circling birds. Prisms rainbow out from the water. This space is so pure and untouched that there has been no need to furnish itself with these elements until you’ve entered them. Now, as you do, we’re popping the tags on some fresh nature one cubic foot at a time. It’s arguably the least bleak and most encouraging effort on the entire release, floating the album out on a memory foam cloud until the brief discordant plucks of, what is literally, the last few notes close the lid on the box.

“so now we have a melting pot of various elements and techniques employed throughout the album. electronics, vocal synthesis etc.etc.“

Tobin‘s intention to wrap up the release by revisiting all of the different aspects that have been explored throughout the rest of the album is in direct correlation to ISAM being an accumulation of all of the styles that the composer has experimented with and perfected over the course of the previous albums that have led up to it. The dark beauty, calculated transitions between tracks, live samples, processing, synthesizing, etc. are all present. It wouldn’t surprise me if the next release is his most minimal work to date. Then again, it wouldn’t surprise me if it were even more elaborate, either.

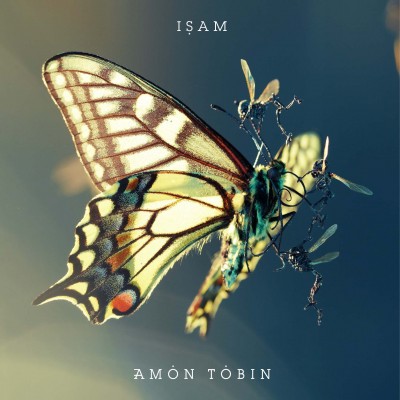

ISAM has been released in a few different versions and packaging options, including a “6 panel gatefold CD, double heavyweight LP with printed inner sleeves, and a limited edition CD artbook featuring exclusive images“. As with the general ISAM cover art (along with the rest of the images in this post) the photos in the artbook are of sculptures created by the UK-based artist Tessa Farmer, who has her work featured in such prestigious collections as the Ashmolean Museum and the Saatchi Gallery. These new artbook featured works in particular -“constructed from bits of organic material, such as roots, dead insects and bones“- were created explicitly for/inspired by the music of ISAM and were actually part of a collaborative installation between Tobin and Farmer earlier this year. The exhibit, titled “Control Over Nature“, was held at The Crypt Gallery at the St Pancras Parish Church in London (originally “designed and used for coffin burials“) and entailed the music from ISAM and Farmer‘s displayed visual work complementing each other to create a collective experience where sight and sound overlap, merging into territories that transcend the typical physical senses.

Tobin‘s audio, on the other hand, was not created with the intention to accompany Farmer‘s sculptural work, whatsoever. His sound collages are painstakingly manufactured to be visual enough on their own. The idea to incorporate the sculptor’s work came after the fact, based on commonalities that the two artists share and recognized in relation to their current approaches to each of their respective fields.

AMON TOBIN:

“we’re both re-arranging and augmenting natural elements to make something imagined but tangible. We are both exploring new uses for familiar materials, or in Tessa’s case familiar creatures. I’m trying to take an objective approach to all my source material, whether it’s field recording or synthesis based or a mixture of the two. I’m treating it all as musically/creatively relevant and useful.“

When asked by NewScientist.com about presenting her work alongside Amon‘s music, Tessa simply states:

“It’s how my work sounds“

While stumbling around the internet -searching out a reference, video, image source, or verification for some random aspect of this article- I came across a link to Pitchfork‘s review of ISAM and, uncharacteristically, decided to go ahead and read it. I can’t remember everything that it said, but I do remember a few key elements. The first is that they gave it a relatively low rating (checking now, I see that it was a mere 5.9) and that score was the primary factor prompting me to reading ahead. The second thing that I recall is that the actual content of the review felt somewhat favorable and didn’t really seem to support that final determination. Maybe it depends on what you’re looking for, because the writer describes various aspects that I saw as positives with the project, while commending Tobin‘s capabilities as an innovator to move forward, but then seemingly contradicts himself by complaining about the artist’s structural tangents and that the album isn’t an accessible, head-nodding effort full of songs that are tightly packaged like little snack treats, more akin to some of his previous work. The last point -and the one thing that really stuck out to me- was that the entire effort was dismissed by the reviewer as nothing more than a “transitional” album. This is a claim that I find to be both semi-accurate and absurdly misguided. Misguided, because I find nothing within ISAM that feels unfinished or like a work in progress. This is a fully realized and expertly developed project that is fascinating and engaging for both it’s emotional qualities, as well as it’s technological accomplishments. I find the claim to be semi-accurate because, with such an innovative and forward thinking artist, everything created is destined to be a “transition” to whatever he opts to tackle next, in one fashion or another. That doesn’t mean that it isn’t also a destination of its own.

The one other dissatisfied accusation that is likely to be directed towards the ISAM project is that Amon Tobin is simply just too self-indulgent. I, myself, might argue that any “real” and “genuine” art is. If others feel that the work is too scattered and unfocused, like that previous reviewer, I have to question how engaged they have really allowed themselves to become with the piece. A certain level of objectivity is definitely necessary to sufficiently analyze and critique something, but I feel it’s important to remember what/who you are actually writing these reviews for. Shouldn’t there be some effort to try and experience the work in the same way that others who would look to you for your interpretation might? How important is it to be able to share what you’ve discovered with the world? How important is it to just have the soapbox? I guess that what I’m asking is, “how self-indulgent is it to scrawl out your own critical opinions like this, just to toss them at the world like a raw slab of meat, in the first place?” My assumption is that, to Amon Tobin, that opportunity to share what HE’s discovered with the world is probably the most important thing there is. I feel that any mind-numbing technical legwork put into the project, that might be interpreted as general pretentiousness, has been more than validated by their end result. His ability to finely tune and control each tiny fragment wasn’t simply used as a gimmick, it’s actually allowed him to form little moments of sound and pure emotion that, although they may have already existed in his head, would have been unavailable to him (and us) otherwise. It’s like an amateur guitar “virtuoso” churning out some intricate Eddie Van Halen finger taps or cornball Joe Satriani licks. If there’s no deeper connection to the music or what they’re doing besides the recognition of the difficulty involved -as is often the case- it can come across as the self-indulgent equivalent to flexing with one arm and smearing your own load into your belly flesh with the other. But, what if that technique is utilized in a way that actually benefits the music and you connect to it; finding yourself traveling in a loin cloth through a firey swamp on the back of a pegasus, your experience is actually transformed, and you’re really into that type of shit? Well, then it’s hard to argue that, at the very least, some of that showboating wasn’t self-indulgent at all, but was actually created for your benefit. The level of self-indulgence that someone finds in a work might just be solely reliant on each individual’s level of personal connection to it, which -if you think about it- is actually somewhat ironic. It’s difficult to fault someone for putting in such tremendous research, time, and efforts of tedium to be able to construct elaborate worlds, simply for our exploration. And that’s what they are, open environments built for the listener.

As a reviewer, I find it nearly impossible to stand back and attempt to summarize this album through nothing, but logic and assessments restricted to it’s individual components. ISAM is far too emotionally driven for that. This is the type of project that you actually have to get inside of and wear for a minute. Tobin has stated time and time again that it was not intended to be a “concept” album or even one of abstract experimentation in musique concrète. It’s supposed to be an album that can be enjoyed by the listener on a level beyond intellectual appreciation. You know… musically. It’s hard to deny that there are fragmented moments and disjointed components throughout the album, but it’s the listener’s duty, as well as privilege, to be able to connect those dots themselves and fill in those gaps through their own personal experiences with, and reactions to, the material. Real art exists off of the page, or canvas, or even the soundwave, or… whatever the medium. Whether it’s through his music, Tessa Farmer‘s sculptures, or the elaborate and groundbreaking mutli-media live performance created for ISAM (covered/reviewed in part 2), a simple concrete narration is never provided; there’s always space to interject your own highly specific and personalized outlook into it. Everything from the processing to the arrangements on the album are used to agitate and stoke the embers of the listener, beckoning them to follow the electronic piper like Victorian spectres through environments that unfold like a crossover episode of Ghost Hunters and American Pickers set on Cyberton. With ISAM, Amon Tobin has managed to ride a very delicate balance; neither shamelessly pandering to his audience’s expectations or completely abandoning them in the woods without a handful of breadcrumbs. If there’s one thing that’s become predictable about the electronic pioneer throughout his decade-and-a-half career, it’s that you can never predict exactly what he’s gonna do next. He’s one of the most consistently forward thinking artists out there, in electronic music or any genre. With ISAM, he has produced, what I believe to be, one of the most impressive projects of the year and I enthusiastically welcome whatever direction he chooses to venture into next. I’m sure that there are others who would disagree with that sentiment, but Tobin doesn’t seem overly concerned if members of his fanbase do choose to jump ship. It’s like he states with the comment that he’s chose to lead off the soundcloud stream with:

“anyone looking for jazzy brks should look elsewhere at this point or earlier :). it’s 2011 folks, welcome to the future.“